- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

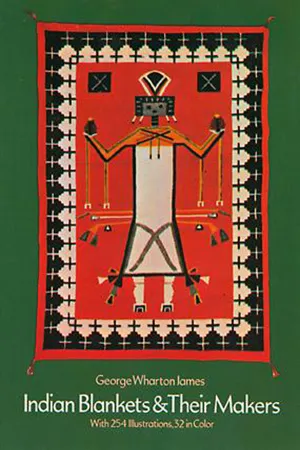

Indian Blankets and Their Makers

About this book

History, old-style wool blankets, changes brought about by traders, symbolism of design and color, a Navajo weaver at work, more. Emphasis on Navajo. Includes information on the Bayeta blanket, squaw dresses, dyeing, belts, garters, hair braids, imitation blankets, the Chimayó blanket, and reliable dealers. 254 illustrations, 32 in color.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion DesignCHAPTER I

Where Navaho Blankets Are Made

Navaho Houses and Their Songs of Blessing

ONE of the great surprises to him who travels over the Navaho reservation for the first time is that he never sees villages, towns, settlements, or groups of houses of the Navahos. Indeed, he may wander for months and seldom see a hogan unless he watches trails carefully and follows those that seem to be traveled. The Navaho is not a gregarious animal in his home life. He wants his own about him and no more. Association with his fellows he obtains at the trading-store, or at the many ceremonial chantings, dancings, or prayers that his “singing, prayer, and medicine mien” provide for him.

Following one of these trails the visitor may be led into a small arroyo—or dry stream, and there close to the wall, perhaps, is the summer hogan. It may be in the woods, or in the shelter of some rocks, but seldom in the open.

The older Navahos tell us that In the “ far-away days of the old” they used to live in mere dugouts, with a rude covering of a grass and yucca mat secured with yucca cords. This was entered by means of a ladder which was drawn in after use. When a change of domicile was desired both yucca mat-roof and ladder were made into a roll and carried to the new location.

But as conditions improved, the type of dwelling correspondingly improved until the present forms of hogans (pronounced ho-gán) were modeled. The builders claim, however, that these types are sacred and are constructed after legendary designs. There are, broadly speaking, two types, the summer and the winter hogan. Both are miserably crude structures and wholly at variance with the exquisite blankets designed and manufactured therein. One would naturally think that, with the art instinct highly developed in one line, it would assert itself in others, and especially in the structures erected for their homes. Yet as one studies the inner life of the Navaho he may find full explanation of this apparent contradiction. In the first place the Navaho is a partial nomad. Never until now has he really felt himself able to settle down anywhere. He had few or no possessions and his home, therefore, needed to be only a temporary shelter which he might have to leave at a moment’s or an hour’s notice. Hence, why should he make it beautiful, and have his heart grieved at being compelled to forsake it. Superstition also requires the Navahos to burn the hogan after a death has taken place in it. Then, too, the Navaho does not regard the hogan as a white man does his home. The latter lives in his house and goes out of doors as his business or his pleasure demands. The Navaho, on the other hand, lives out of doors. That is his home. He uses his hogan as a convenient place of storage and a stopping place, with the addition, of course, in winter, that it is a comfortable sleeping place which he can make warm. But our idea of a house being a home never enters his mind. He loves the beauty of the out-of-doors. He regards that as his own, and the poetry of his conceptions in a variety of ways is remarkably influenced by the glories of Nature. These, then, are reasons against the making of a more beautiful and permanent dwelling.

Who but a Nature poet, even in his legends, could have conceived of a house (hogan) made as follows, resplendent and magnificent, as did the Navaho creator of the original hogan:

The poles were made of precious stones such as white-shell, turquoise, abalone, obsidian, and red stone, and were five in number. The interstices were lined with four shelves of white-shell, and four of turquoise, and four of abalone and obsidian, each corresponding with the pole of the respective stone, thus combining the cardinal colors of white, blue, yellow and black in one gorgeous edifice. The floor, too, of this structure was laid with a fourfold rug of obsidian, abalone, turquoise, and white shell, each spread over the other in the order mentioned, while the door consisted of a quadruple curtain or screen of dawn, sky-blue, evening twilight, and darkness. As a matter of course the divine builders might increase its size at will, and reduce it to a minimum, whenever it seemed desirable to do so.3

Nor is this the only gorgeous hogan of the poet’s imagination. There are others which were the prototypes of other styles in use today, and also for hogans for especial ceremonial use.

While Father Berard states that the present custom does not require special dedicatory ceremonies at the completion of a hogan, Cosmos Mindeleff, in the Seventeenth Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, gives a full account of them, and they are so wonderful, for a wild and barbaric people, that I cannot refrain from extracting largely. Personally I have witnessed some of these ceremonials, have recorded some of the songs in my graphophone, and have felt that I would like to give to the American civilized, Christian world, a ceremony for the dedication of its houses based on what I have seen and learned of the home-dedication rituals of these heathen, uncivilized, unchristian (!) people.

Brotherly helpfulness is the rule in the erection of a Navaho hogan, and the assistance of friends generally makes it possible to complete the structure in one, or at most two or three days. The wife then sweeps out the interior with a grass broom, and she or her husband lights a fire under the smoke-hole. Then, taking a saucer or bowl-shaped basket she fills it with white corn meal which she hands over to the head of the household. He proceeds to rub a handful of meal on each of the five principal timbers of which the hogan frame is formed, beginning always with the south doorway timber. He rubs the meal on one place, as high up as he can easily reach, and always in the following order: south doorway, south, west, north timbers, and the north doorway timber. All keep reverent silence while this is being done. Next, with a sweeping motion of his hand, sunwise, he sprinkles the meal to the outer circumference of the room, at the same time in a low, measured, chanting tone saying:

May it be delightful, my house;

From my head may it be delightful;

To my feet may it be delightful;

Where I lie may it be delightful;

All above me may it be delightful;

All around me may it be delightful.

From my head may it be delightful;

To my feet may it be delightful;

Where I lie may it be delightful;

All above me may it be delightful;

All around me may it be delightful.

Then, flinging a little meal into the fire he continues:

May it be delightful and well, my fire.

Tossing a handful or two of meal up and through the smoke-hole:

May it be delightful, Sun, my mother’s ancestor, for this

gift;

May it be delightful as I walk around my house.

gift;

May it be delightful as I walk around my house.

Now, sprinkling two or three handfuls out of the doorway he says:

May it be delightful, this road of light [the path of the

Sun], my mother’s ancestor.

Sun], my mother’s ancestor.

The woman of the house now advances, makes a meal-offering to the fire, and says, in a quiet and subdued voice:

May it be delightful, my fire;

May it be delightful for my children; may all be well;

May it be delightful with my food and theirs; may all be

well;

All my possessions well may they be made.

All my flocks well may they be made [that is, may they be

healthful and increase].

May it be delightful for my children; may all be well;

May it be delightful with my food and theirs; may all be

well;

All my possessions well may they be made.

All my flocks well may they be made [that is, may they be

healthful and increase].

Let me quote Cosmos Mindeleff for the remainder of the description:

Night will have fallen ... all now gather inside, the blanket is suspended over the door-frame, all the possessions of the family are brought in, sheepskins are spread on the floor, the fire is brightened, and the men all squat around it. The women bring in food in earthen cooking pots and basins, and, having set them down among the men, they huddle together by themselves to enjoy the occasion as spectators. Everyone helps himself from the pots by dipping in with his fingers, the meat is broken into pieces, and the bones are gnawed upon and sociably passed from hand to hand. When the feast is finished tobacco and corn husks are produced, cigarettes are made, everyone smokes, and convivial gossipy talk prevails, This continues for two or three hours, when the people who live near by get up their horses and ride home. Those from a long distance either find places to sleep in the hogan or wrap themselves in their blankets and sleep at the foot of a tree. This ceremony is known as the qogán aiila, a kind of salutation to the house.

But the house devotions have not yet been observed. Occasionally these take place as soon as the house is finished, but usually there is an interval of several days to permit the house builders to invite all their friends and to provide the necessary food for their entertainment. Although analogous to the Anglo-Saxon “house-warming,” the house devotions, besides being a merrymaking for the young people, have a much more solemn significance for the elders. If they be not observed soon after the house is built bad dreams will plague the dwellers therein, toothache (dreaded for mystic reasons) will torture them, and the evil influence from the north will cause them all kinds of bodily ill; the flocks will dwindle, ill luck will come, ghosts will haunt the place, and the house will become batsic, tabooed.

A few days after the house is finished an arrangement is made with some shaman (devotional singer) to come and sing the ceremonial house songs. For this service he always receives a fee from those who engage him, perhaps a few sheep or their value, sometimes three or four horses or their equivalent, according to the circumstances of the house-builders. The social gathering at the house-devotion is much the same as that of the salutation to the house, when the house is built, except that more people are usually invited to the former. They feast and smoke, interchange scandal, and talk of other topics of interest, for some hours. Presently the shaman seats himself under the main west timber so as to face the east, and the singing begins.

In this ceremony no rattle is used. The songs are begun by the shaman in a drawling tone and all the men join in. The shaman acts only as leader and director. Each one, and there are many of them in the tribe, has his own particular songs, fetiches, and accompanying ceremonies, and after he has pitched a song he listens closely to hear whether the correct words are sung. This is a matter of great importance, as the omission of a part of the song or the incorrect rendering of any word would entail evil consequences to the house and its inmates. All the house songs of the numerous shamans are of similar import, but differ in minor details.

The first song is addressed to the east, and is as follows:

Far in the east far below there a house was made;

Delightful house.

God of Dawn there his house was made;

Delightful house.

The Dawn there his house was made;

Delightful house.

White corn there its house was made;

Delightful house.

Soft possessions for them a house was made;

Delightful house.

Water in plenty surrounding for it a house was made;

Delightful house.

Corn pollen for it a house was made;

Delightful house.

The ancients make their presence delightful;

Delightful house.

Delightful house.

God of Dawn there his house was made;

Delightful house.

The Dawn there his house was made;

Delightful house.

White corn there its house was made;

Delightful house.

Soft possessions for them a house was made;

Delightful house.

Water in plenty surrounding for it a house was made;

Delightful house.

Corn pollen for it a house was made;

Delightful house.

The ancients make their presence delightful;

Delightful house.

Immediately following this song, but in a much livelier measure, the following benedictory chant is sung:

Before me may it be delightful;

Behind me may it be delightful;

Around me may it be delightful;

Below me may it be delightful;

Above me may it be delightful;

All (universally) may it be delightful.

Behind me may it be delightful;

Around me may it be delightful;

Below me may it be delightful;

Above me may it be delightful;

All (universally) may it be delightful.

After a short interval the following is sung to the west:

Far in the west far below there a house was made;

Delightful house.

God of Twilight there his house was made;

Delightful house.

Yellow light of evening there his house was made;

Delightful house.

Yellow corn there its house was made;

Delightful house.

Hard possessions there their house was made;

Delightful house.

Young rain there its house was made;

Delightful house.

Corn pollen there its house was made;

Delightful house.

The ancients make their presence delightful;

Delightful house.

Delightful house.

God of Twilight there his house was made;

Delightful house.

Yellow light of evening there his house was made;

Delightful house.

Yellow corn there its house was made;

Delightful house.

Hard possessions there their house was made;

Delightful house.

Young rain there its house was made;

Delightful house.

Corn pollen there its house was made;

Delightful house.

The ancients make their presence delightful;

Delightful house.

The song to the west is also followed by the benedictory chant, as above, and after this the song which was sung to the east is repeated; but this time it is addressed to the south. The song to the west is then repeated, but addressed to the north, and the two songs are repeated alternately until each one has been sung three times to each cardinal point. The benedictory chant is sung between each repetition.

All the men present join in the singing under the leadership of the shaman, who does not himself sing, but only starts each song. The women never sing at these gatherings, although on other occasions, when they get together by themselves, they sing very sweet...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON WEAVING AND RELATED AREAS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- INTRODUCTION

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- CHAPTER I

- CHAPTER II

- CHAPTER III

- CHAPTER IV

- CHAPTER V

- CHAPTER VI

- CHAPTER VII

- CHAPTER VIII

- CHAPTER IX

- CHAPTER X

- CHAPTER XI

- CHAPTER XII

- CHAPTER XIII

- CHAPTER XIV

- CHAPTER XV

- CHAPTER XVI

- CHAPTER XVII

- CHAPTER XVIII

- CHAPTER XIX

- CHAPTER XX

- CHAPTER XXI

- CHAPTER XXII

- APPENDIX

- INDEX

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Indian Blankets and Their Makers by George Wharton James in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.