- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lectures on Architecture, Volume I

About this book

Volume 1 of an unabridged reprint of extremely influential work by great 19th-century architect, champion of the Gothic Revival. Coverage of Greek and Roman architecture, Byzantine architecture, teaching of architecture, monumental sculpture, domestic architecture, much more. Over 230 engravings and woodcuts (most by Viollet-le-Duc) enhance the text. Republication of rare English edition (1877—1881).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArquitecturaSubtopic

Historia de la arquitecturaLECTURE VII.

THE PRINCIPLES OF WESTERN ARCHITECTURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

THE Architecture of the Ancients was long studied without any account being taken of the effects produced by the colouring of the form; whether this colouring was produced by mosaic, marble veneering, or painting on stucco. The Orientals and Greeks, and even the Romans rejected the principle that the naked material of which an edifice was constructed should remain visible. The Greeks coloured white marble when they employed that beautiful material. However slight that colouring may have been (though everything leads us to suppose that it was on the contrary strong and vivid), its result was none the less that of concealing the real material under a kind of tapestry independent of that material. I am not one of those who would allow that the Greeks could have adopted a false principle in the execution of works of art; and if we find them adopting modes of procedure that are apparently strange, and to which we find it difficult to accustom our eyes, I should rather believe in the imperfection of our senses than in an error on the part of these masters in art.

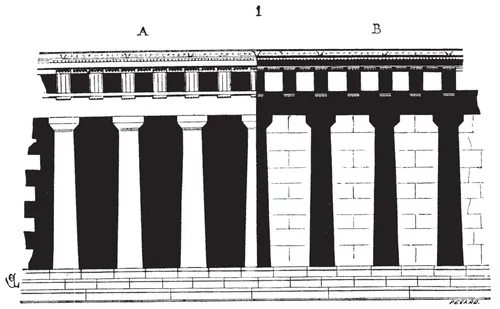

It is now some time since archaeologists and artists made clear, even to the most incredulous, that all the Greek monuments had a colouring both outside and inside, laid on a thin coat of stucco when the stone was of a coarse grain, and on the smooth surface of the marble itself, when the building was of that material. This indisputable fact leads us to suppose that the Greeks did not regard the form alone as sufficient for architectural effect, but considered that this form should be completed, aided or modified by a combination of various colours. No lengthened experience in matters of art is needed to show what an influence colour has on form, and even on proportions : if, for example, we were to colour black the metopes and the wall of the cella of a Greek temple, we should obtain an effect quite different from that which would result from leaving these metopes and the wall white, and covering the cornice, the triglyphs, the architrave, and columns black (fig. 1), all the real dimensions and proportions remaining the same. The result of the first method of colouring would be to give breadth to the order, and importance to the architrave, the triglyphs, and the cornice ; that of the second, indicated at B, would be to make the columns appear more slender and lofty, while the entablature would lose in importance. Colouring therefore greatly influenced the effect produced by architecture ; and in the present day we cannot form a correct. judgment of the ancient Greek buildings without taking the colouring into account. An order that seems to us heavy might have appeared slender ; another whose proportions seem delicate would present a firm and solid appearance.

FIG. 1.—Effect of Colouring on Proportions.

The senses of the Greeks were too delicate to allow of their failing to understand the advantage that could be gained from the recognition of this principle in architecture, or neglecting so powerful means of visual effect in giving a different signification to form—shall I say—by dint of variety of colouring. We are subjected to the sway of deeply-rooted prejudices, so that our senses refuse to recognise facts which are nevertheless in strict consistency with natural laws. In sculpture and architecture we have been long accustomed to admit the effect of form as the only legitimate one, as if an object in relief must on that account dispense with colouring. On what is this sentiment based ? I will try to give the reason; and the question is especially interesting, inasmuch as this sentiment is the result of new principles whose importance is perhaps not duly appreciated. We have here another of those innumerable contradictions which in our times have led art astray. Some uncompromising admirers of Classic Architecture insist on the rejection of colour as an aid to form, although the ancients always admitted this means of effect : and in their unwillingness to admit of colour in architecture, they are carrying to excess the tendencies of the mediaeval architects who gave to structure an importance previously unknown. To show more clearly what I mean, it is as if one should say, “I approve of no other mode of architecture but that adopted in classic times, but with the understanding that the most powerful appliance for producing certain effects befitting the object, and which was actually used by the ancient architects, shall not be employed ; I think it right to exclude the architectural methods employed during the Middle Ages, but I maintain that the results to which those methods have given rise ought permanently to exercise a dominant influence over our architecture.”

The Asiatics coloured their architecture.

The Egyptians coloured their architecture.

The Greeks coloured their architecture.

The Romans coloured their architecture, either by painting or by the employment of materials of various colours.

The Arabs coloured their architecture.

During the Byzantine and the Western Romanesque period, the colouring of architecture was continued.

During the period called Gothic, architecture was coloured as a result of traditional influences; but in consequence of the refinements in structure introduced by the leading architects of this epoch, the colouring of buildings was gradually abandoned, with a view to render the complicated and skilful combinations exhibited in the construction conspicuously evident. Painting was no longer architectural, and was thenceforth applied only in exceptional cases.

Among all the ancient nations, and during the earlier mediaeval centuries, an edifice was not considered complete until colour had been called in to enhance the effect of form. But from the thirteenth century onward, architectural form in France can dispense with this complement; form becomes effective simply as the result of structural combinations ; geometry bears away the palm from painting; painting is regarded as a luxury, a sumptuous addition, a decoration ; but architecture can and does dispense with it. These two arts, architecture and painting, though essentially connected, tend constantly towards separation ; till at last we find paintings hung on whitewashed walls, without the painter and the architect having foreseen, respectively,—the one that his painting would be hung up in such or such a building,—the other that his building would receive such or such a picture.

That regard for harmony without which art cannot exist, has long been lost to us. The architect ought to be also a painter and sculptor to such a degree as to enable him to comprehend the advantages to be derived from these two arts which are allied to his own ; the sculptor and the painter ought to be sufficiently alive to the effects produced by architecture not to disdain to contribute to enhance those effects. But this is not the case now : the architect erects his building, and gives it certain forms that are suitable to it; then, when the building is finished, it is given over to the painter. The chief object of the latter is to secure attention to his painting; he cares little for that general effect which even the architect himself has not considered. The statuary is at work in his studio, and his bas-reliefs or statues will some day or other take their place in the building. The architect, the painter, and the sculptor may each have displayed remarkable talent in his own department, yet the work as a whole may produce only a mediocre effect : the statuary is not proportioned to the building, or it presents an effect of agitation when the eye seeks repose; the painting overpowers the architecture, or seems to have no relation with it; it is sombre where we could wish for a light effect, garish where sobriety is desirable. These three arts conflict with, instead of aiding, each other. As a matter of course, the architect, the sculptor, and the painter accuse each other of the non-success of the result as a whole. We are unacquainted with the relations that existed between architects, sculptors, and painters in classical or mediaeval times ; but the aspect of the extant monuments assures us that such relations existed, and that they were direct, continuous, and intimate. I do not believe that the artists were the worse by the connection, while it is certain that art gained by it. Traces of this alliance between the arts continue to appear during the seventeenth century, at least in the interior of palaces ; the galleries of Apollo, at the Louvre, of the Hotel Lambert, and even that of the Marbles at Versailles, offer us the last specimens of a harmony between the three arts,—which must advance in union if they would produce great effects. This invaluable alliance was broken from the moment when architecture shut itself up in the prejudices of the schools, when the painter produced pictures and not painting, and the sculptors statues and not statuary. The museums and the galleries of amateurs were filled, and the public buildings were stripped of their proper ornament ; the opinion was established that architecture allowed only stone in its cold and naked whiteness ; and those who would have refused to live in apartments not hung with gaudily-coloured papers, rejected all colouring in the temple erected to God or the hall of a palace. Moreover, since the opinion prevails among us that the arts ought to be encouraged, painters have been commissioned to execute pictures, and these pictures have been hung up in edifices which their painters had never seen —painted and hung in utter despite of the forms of the architecture, the dimensions of the interiors, and the direction of the light. Sculptors were commissioned to carve statues, which they were well capable of doing; but they had no notion as to where they were to be placed. We cannot, therefore, boast ourselves of being a people endowed with sensibility in matters of art, since we have ceased to be convinced of the necessity of that harmony between arts, whose very nature requires that they advance in concert. During all the best periods of art, sculpture and painting have been the decorative dress of architecture,—a dress made for the body to which it is applied, and which cannot be left to chance. But to preserve that authority which it had acquired over the other arts, it was necessary above all things that architecture should respect itself, and render itself worthy of that decorative dress which was formerly deemed indispensable to it.

At the present day we behold the remains of Classical Antiquity in a state of ruin, all bearing the marks of barbarism, violence, and devastation. These ruins are often buried in dust or mud, and surrounded by shapeless débris ; but the ancients, when such beautiful structures were first erected, were not indifferent as to their surroundings, but carefully selected their position ; they took care to provide a gradual and skilful transition from the highway to the sanctuary of the divinity ; and at Athens and Rome the temples and palaces never rose absolutely from the mud of the streets as is the case with most of our public buildings. That exterior colouring of buildings which would appear ridiculous in our country (as it is ridiculous to see a person dressed in a brilliant costume in the street) was in ancient times a very important architectural element, owing to the care that was taken to render those edifices secure from injury of any kind, the due preparation of their site and the accessories by which they were surrounded. We find these sentiments of respect for a work of art very strongly developed among the Orientals. It appears to us consistent that a pagoda should be coloured from its base to its summit with brilliant colours, inlaid work; and enamelling, when the pagoda is approached only through a series of courts, narrowing in dimensions and increasing in magnificence, elaborately paved with marble and adorned with shrubs and fountains. The sumptuous decorations of the Egyptian sanctuaries can be understood when we consider that those pylones, porticoes, and halls whose magnificence increases as we advance, had to be passed before the temple itself was reached. And we can appreciate the brilliant colouring of the Greek temple when we see by how many artistic objects it was surrounded ; when we imagine to ourselves the sacred woods and enclosures and the thousand accessories whose presence led up to that last and most finished expression of architectural art.

We have been too forgetful of the consideration that works of art require a mise en scène. The ancients never abandoned this principle ; the Middle Ages often endeavoured to adopt it, though with evidently inferior success, especially in France : for in Italy we still recognise the influence of pagan traditions ; and this will largely account for the effect produced by the architectural works of that country; whereas, taken by themselves, these works are often much inferior to what we have in France. There is an art in setting off a work of art, though for a long time we seem to have ceased to think so. We will frankly allow that this kind of negligence, which belongs to our national idiosyncracies, results from a noble and admirable element of character, but this result might be avoided without sacrificing the advantages of the principle in which it had its root. To effect this we must gain an exact acquaintance with our special aptitudes, and lay aside certain prejudices, crude or obsolete doctrines, and vulgar prepossessions against which we artists, through weakness or ignorance, have not the courage or the means boldly to struggle.

Mingled perhaps with other elements of character we possess those qualities which are most adapted to the development of the arts, and of architecture in particular ; yet not only are we unable to take advantage of them, but we allow them to be crushed under that tyranny of vulgar prejudices which enslaves us, because we wish to appear other than we really are, and neglect the precious endowments that have fallen to our share. We erect a public monument, but we give it an unsuitable position and undesirable surroundings; we do not know how to present it to the public; it may be a chef-d’œuvre, but we have managed so as to expose it to desecration. We have not had the sense to respect our work, consequently no one else respects it ;—what else ought we to expect ? The most insignificant buildings of the Middle Ages or of modern times, built in Italy, are always placed with a view to effect ; the picturesque plays an important part. For this we have substituted symmetry, which contravenes our genius, is irksome to us and fatigues us ; it is the last resource of incapacity. Neither the Acropolis of Athens nor the Forum of Rome, nor that of Pompeii, nor the descriptions given us by Pausanius, present us with symmetrical groupings of buildings. Among the Greeks symmetry is consulted in regard to a single building,—though exceptions are abundant,—never in a group of buildings. The Romans themselves, who admitted this principle in the arrangement of architectural masses, never sacrificed utility, good sense, or the necessities of the structure to it. But with what art did the Greeks dispose their public buildings ! What a just appreciation of effect—of what we now call the picturesque ! an object of contempt to our architects. And why ? Because the building as drawn on paper generally takes no account of the place, the aspect, the effects of lights and shadows, the surroundings, or the variations of level—which are, however, such an aid to the display of architectural forms ; because the architect, even before considering how he shall faithfully satisfy the requirements of the programme, makes it his first thought to erect symmetrical equiponderant façades,—a great box in which the various services will have to find their place afterwards as best they can. There is no need, I think, to cite examples to prove that this is no exaggeration. A glance around us will be all-sufficient. Still, if we erected these great regular boxes on platforms, or terraces, or vast basements, as the Romans always did in similar cases, and as was done in our own country at Versailles and St. Germain, in the seventeenth century; if we gave them proper surroundings, and endeavoured to give effect to such dignity as may attach to them as an ensemble of symmetrical lines, by isolating them from the other buildings of our cities, there would be a reason, or at least an excuse for this fondness for symmetry; but no, these huge piles are lost in masses of buildings, their basements are in the gutter, their façades can be seen only one at a time, and it is only on paper, and looking at the plans, that we can give ourselves the satisfaction of thinking that the right wing is exactly of the same length and breadth as the left. The Romans—but above all the Greeks—never adopted a symmetrical arrangement except when it could be recognised at a glance,—that is in a space sufficiently limited for the eye to be satisfied, without the aid of reasoning, by a balanced disposition of the structure. But if we have to go half a mile or more to enable us to see that the facade on the north side—supposing we have a visual memory sufficient for the purpose—corresponds with that on the south ; if we have to leave one court and enter another to perceive—continuing the supposition that our memory does not fail us—that these courts are exactly similar, I ask what purpose is served by abandoning common sense, inconveniencing the internal arrangements of the building, and thwarting the requirements of the scheme, to obtain so puerile a result, which only serves to amuse a few curious idlers ?

What authority can be appealed to in support of these so frequent examples of absurdity ? Mediæval traditions ?...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE.

- THE AUTHOR’S PREFACE.

- LECTURE I.

- LECTURE II.

- LECTURE III.

- LECTURE IV.

- LECTURE V.

- LECTURE VI.

- LECTURE VII.

- LECTURE VIII.

- LECTURE IX.

- LECTURE X.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lectures on Architecture, Volume I by Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Historia de la arquitectura. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.