![]()

CHAPTER I.

THE HOUSE.

APPEARANCE OF CITY AND VILLAGE. — GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF HOUSE. — HOUSE CONSTRUCTION. — FRAMEWORK AND FOUNDATION. — BRACING. — SELECTION OF STOCK. — CONSTRUCTION OF CEILING. — PARTITIONS AND WALLS. — STRUCTURE OF KURA. — JAPANESE CARPENTERS. — CARPENTERS’ TOOLS AND APPLIANCES.

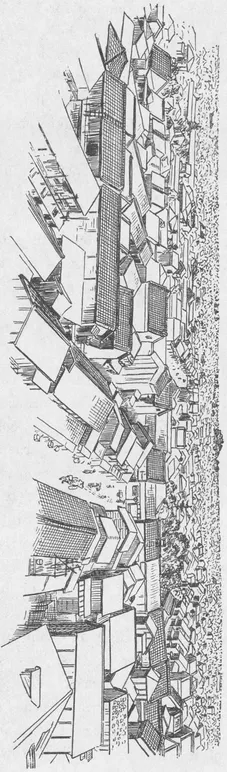

A BIRD’S-EYE view of a large city in Japan presents an appearance quite unlike that presented by any large assemblage of buildings at home. A view of Tokio, for example, from some elevated point reveals a vast sea of roofs, — the gray of the shingles and dark slate-color of the tiles, with dull reflections from their surfaces, giving a sombre effect to the whole. The even expanse is broken here and there by the fire-proof buildings, with their ponderous tiled roofs and ridges and pure white or jet-black walls. These, though in color adding to the sombre appearance, form, with the exception of the temples, one of the most conspicuous features in the general monotony. The temples are indeed conspicuous, as they tower far above the pigmy dwellings which surround them. Their great black roofs, with massive ridges and ribs, and grand sweeps and white or red gables, render them striking objects from whatever point they are viewed. Green masses of tree-foliage springing from the numerous gardens add some life to this gray sea of domiciles.

It is a curious sight to look over a vast city of nearly a million inhabitants, and detect no chimney with its home-like streak of blue smoke. There is of course no church spire, with its usual architectural inanities. With the absence of chimneys and the almost universal use of charcoal for heating purposes, the cities have an atmosphere of remarkable clearness and purity; so clear, indeed, is the atmosphere that one may look over the city and see distinctly revealed the minuter details of the landscape beyond. The great sun-obscuring canopy of smoke and fumes that forever shroud some of our great cities is a feature happily unknown in Japan.

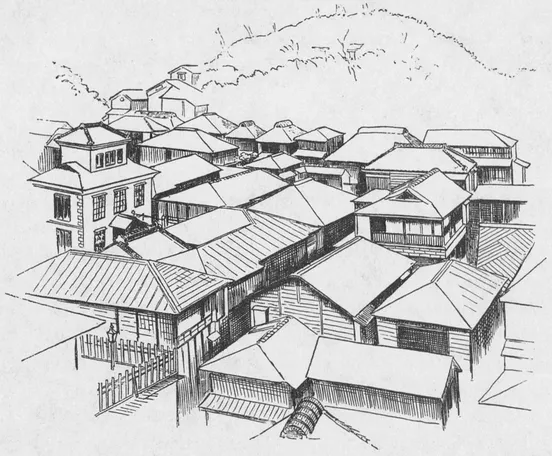

Having got such a bird’s-eye view of one city, we have seen them all, — the minor variations consisting, for the most part, in the inequalities of the sites upon which they rest. A view of Kioto, for example, as seen from some high point, is remarkably beautiful and varied, as the houses creep out between the hills that hem it in. In Nagasaki the houses literally rise in tiers from the water’s edge to the hills immediately back, there to become blended with the city of the dead which caps their summits. A view of Nagasaki from the harbor is one of surpassing interest and beauty. Other large cities, such as Sendai, Osaka, Hiroshima, and Nagoya present the same uniform level of roofs.

The compact way in which in the cities and towns the houses are crowded together, barely separated by the narrow streets and lanes which cross like threads in every direction, and the peculiarly inflammable material of which most of the buildings are composed, explains the lightning-like rapidity with which a conflagration spreads when once fairly under way.

In the smaller villages the houses are stretched along the sides of a single road, nearly all being arranged in this way, sometimes extending for a mile or more. Rarely ever does one see a cross street or lane, or evidences of compactness, save that near the centre of this long street the houses and shops often abut, while those at the end of the streets have ample space between them. Some villages, which from their situation have no chance of expanding, become densely crowded : such for example is the case of Enoshima, near Yokohama, wherein the main street runs directly from the shore, by means of a series of steps at intervals, to a flight of stone steps, which lead to the temples and shrines at the summit of the island. This street is flanked on both sides by hills; and the ravine, of which the street forms the central axis, is densely crowded with houses, the narrowest of alley-ways leading to the houses in the rear. A fire once started would inevitably result in the destruction of every house in the village.

FIG. 1. — A VIEW IN TOKIO, SHOWING SHOPS AND HOUSES. (COPIED FROM A PHOTOGRAPH)

FIG. 2. — A VIEW IN TOKIO, SHOWING TEMPLES AND GARDENS. (COPIED FROM A PHOTOGRAPH.)

It is a curious fact that one may ride long distances in the country without passing a single dwelling, and then abruptly enter a village. The entrance to a village is often marked by a high mound of earth on each side of the road, generally surmounted by a tree; or perhaps the evidences of an old barrier are seen in the remains of gate-posts or a stone-wall. Having passed through the village one enters the country again, with its rice-fields and cultivated tracts, as abruptly as he had left it. The villages vary greatly in their appearance : some are extremely trim and pretty, with neat flower-plats in front of the houses, and an air of taste and comfort everywhere apparent ; other villages present marked evidences of poverty, squalid houses with dirty children swarming about them. Indeed, the most striking contrasts are seen between the various villages one passes through in a long overland trip in Japan.

It is difficult to imagine a more dreary and dismal sight than the appearance of some of these village streets on a rainy night. No brightly-lighted window cheers the traveller; only alleys, lined with a continuous row of the cheapest shelters ; and here dwell the poorest people. Though squalid and dirty as such places appear to the Japanese, they are immaculate in comparison with the unutterable filth and misery of similar quarters in nearly all the great cities of Christendom. Certainly a rich man in Japan would not, as a general thing, buy up the land about his house to keep the poorer classes at a distance, for the reason that their presence would not be objectionable, since poverty in Japan is not associated with the impossible manners of a similar class at home.

Before proceeding with a special description of Japanese homes, a general description of the house may render the chapters that are to follow a little more intelligible.

The first sight of a Japanese house, — that is, a house of the people, — is certainly disappointing. From the infinite variety and charming character of their various works of art, as we had seen them at home, we were anticipating new delights and surprises in the character of the house ; nor were we on more intimate acquaintance to be disappointed. As an American familiar with houses of certain types, with conditions among them signifying poverty and shiftlessness, and other conditions signifying refinement and wealth, we were not competent to judge the relative merits of a Japanese house.

The first sight, then, of a Japanese house is disappointing ; it is unsubstantial in appearance, and there is a meagreness of color. Being unpainted, it suggests poverty; and this absence of paint, with the gray and often rain-stained color of the boards, leads one to compare it with similar unpainted buildings at home, — and these are usually barns and sheds in the country, and the houses of the poorer people in the city. With one’s eye accustomed to the bright contrasts of American houses with their white, or light, painted surfaces ; rectangular windows, dim lines of light glimmer through the chinks of the wooden shutters with which every house is closed at night. On pleasant evenings when the paper screens alone are closed, a ride through a village street is often rendered highly amusing by the grotesque shadow-pictures which the inmates are unconsciously projecting in their movements to and fro.

FIG. 3. — VIEW OF ENOSHIMA. (COPIED FROM A PHOTOGRAPH.)

In the cities the quarters for the wealthier classes are not so sharply defined as with us, though the love for pleasant outlooks and beautiful scenery tends to enhance the value of certain districts, and onsequently to bring together the wealthier classes. In nearly all the cities, however, you will find the houses of the wealthy in the immediate vicinity of the habitations of the poorest. In Tokio one may find streets, or narrow black from the shadows within, with glints of light reflected from the glass; front door with its pretentious steps and portico ; warm red chimneys surmounting all, and a general trimness of appearance outside, which is by no means always correlated with like conditions within, — one is too apt at the outset to form a low estimate of a Japanese house. An American finds it difficult indeed to consider such a structure as a dwelling, when so many features are absent that go to make up a dwelling at home, — no doors or windows such as he had been familiar with; no attic or cellar; no chimneys, and within no fire-place, and of course no customary mantle; no permanently enclosed rooms; and as for furniture, no beds or tables, chairs or similar articles, — at least, so it appears at first sight.

One of the chief points of difference in a Japanese house as compared with ours lies in the treatment of partitions and outside walls. In our houses these are solid and permanent; and when the frame is built, the partitions form part of the framework. In the Japanese house, on the contrary, there are two or more sides that have no permanent walls. Within, also, there are but few partitions which have similar stability; in their stead are slight sliding screens which run in appropriate grooves in the floor and overhead. These grooves mark the limit of each room. The screens may be opened by sliding them back, or they may be entirely removed, thus throwing a number of rooms into one great apartment. In the same way the whole side of a house may be flung open to sunlight and air. For communication between the rooms, therefore, swinging doors are not necessary. As a substitute for windows, the outside screens, or

shji, are covered with white paper, allowing the light to be diffused through the house.

Where external walls appear they are of wood unpainted, or painted black; and if of plaster, white or dark slate colored. In certain classes of buildings the outside wall, to a height of several feet from the ground, and sometimes even the entire wall, may be tiled, the interspaces being pointed with white plaster. The roof may be either lightly shingled, heavily tiled, or thickly thatched. It has a moderate pitch, and as a general thing the slope is not so steep as in our roofs. Nearly all the houses have a verandah, which is protected by the widely-overhanging eaves of the roof, or by a light supplementary roof projecting from beneath the eaves.

While most houses of the better class have a definite porch and vestibule, or genka, in houses of the poorer class this entrance is not separate from the living room; and since the interior of the house is accessible from two or three sides, one may enter it from any point. The floor is raised a foot and a half or more from the ground, and is covered with thick straw mats, rectangular in shape, of uniform size, with sharp square edges, and so closely fitted that the floor upon which they rest is completely hidden. The rooms are either square or rectangular, and are made with absolute reference to the number of mats they are to contain. With the exception of the guest-room few rooms have projections or bays. In the guest-room there is at one side a more or less deep recess divided into two bays by a slight partition; the one nearest the verandah is called the tokonoma. In this place hang one or more pictures, and upon its floor, which is slightly raised above the mats, rests a flower vase, incense burner, or some other object. The companion bay has shelves and a low closet. Other rooms also may have recesses to accommodate a case of drawers or shelves. Where closets and cupboards occur, they are finished with sliding screens instead of swinging doors. In tea-houses of two stories the stair...