This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The `Gilded Age,` the three decades following the Civil War, were years of astounding economic growth. Vast empires in oil, shipping, mining, banking, lumber, transportation, and related industries were formed. It was an era in which fortunes were made and lost quickly, almost easily; a period that encouraged ― nearly demanded ― the public display of this newly acquired wealth, power, and prestige. It was during these heady, turbulent years that a new type of domestic architecture first appeared on the American landscape. Called the `country seat` or `cottage,` these houses were grandiose in scale ― imposing facades complemented by manicured gardens, with exceptionally large and impressive reception rooms, halls, parlors, dining rooms, and other public areas. Intended exclusively for the very well-to-do, these buildings were designed by some of the finest and most influential architectural firms in America: McKim, Mead & White; Bruce Price; Peabody & Stearns; Theophilus P. Chandler, Jr.; Lamb & Rich; Wilcox & Johnston; and many others.

The first, best, and most exquisite documentation of this surge of architectural creativity was the 1886–87 publication of George William Sheldon's Artistic Country-Seats: Types of Recent American Villa and Cottage Architecture with Instances of Country-Club Houses. It presented exceedingly fine photographs, clearly detailed plans and elevations, as well as Sheldon's own commentary for a total of 97 buildings (93 houses and 4 casinos). Most structures were located in new England and the Middle Atlantic states, and embraced the full spectrum of architectural and artistic expressions. This present volume reproduces all of Sheldon's fascinating and historically important photographs and plans, and adds a new, thoroughly accurate text by Arnold Lewis (Professor of Art, the College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio) that includes the most useful information supplied by Sheldon and also reports on the present condition of each house or casino, providing analyses of elevations and plans, observations about family life in the 1880s, and brief biographical comments about the clients and architects.

Sheldon's photographs connect us with a time and style of living that today increasingly seem more the realm of fiction than fact. Yet, in the pages of this important collection, they are brought fresh to life as they appeared when they were new and times were very different.

The first, best, and most exquisite documentation of this surge of architectural creativity was the 1886–87 publication of George William Sheldon's Artistic Country-Seats: Types of Recent American Villa and Cottage Architecture with Instances of Country-Club Houses. It presented exceedingly fine photographs, clearly detailed plans and elevations, as well as Sheldon's own commentary for a total of 97 buildings (93 houses and 4 casinos). Most structures were located in new England and the Middle Atlantic states, and embraced the full spectrum of architectural and artistic expressions. This present volume reproduces all of Sheldon's fascinating and historically important photographs and plans, and adds a new, thoroughly accurate text by Arnold Lewis (Professor of Art, the College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio) that includes the most useful information supplied by Sheldon and also reports on the present condition of each house or casino, providing analyses of elevations and plans, observations about family life in the 1880s, and brief biographical comments about the clients and architects.

Sheldon's photographs connect us with a time and style of living that today increasingly seem more the realm of fiction than fact. Yet, in the pages of this important collection, they are brought fresh to life as they appeared when they were new and times were very different.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access American Country Houses of the Gilded Age by A. Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

History of ArchitectureAMERICAN COUNTRY HOUSES OF THE GILDED AGE

(Sheldon’s “Artistic Country-Seats”)

1. Harry Fenn residence, Montclair, N.J.; H. Edwards Ficken, architect, 1884. In 1885 the Magazine of Art (London) published an article about this house, recently completed for the watercolorist and illustrator Harry Fenn. There were two reasons for this article. For one thing, Fenn was well known in England. Born in Richmond, Surrey, in 1838, he settled in the United States in 1857 but retained close ties with his native country, where his sketches were seen frequently in the popular magazines of the day and also in several books, among them Picturesque America and Picturesque Europe. Secondly, the journal used the opportunity to acknowledge the rising quality of American architecture. “Now, although the younger architects of America, as might be expected of men who have broken with tradition, have quite generally fallen into an unchastened, mongrel style, full of affectations and overladen with bad ornament, still this much may be said for them, that they have almost as generally sought to secure comfort and convenience as well as a picturesque outline, and a warm and harmonious scheme of colour as well as an abundance of rather cheap decoration.” Fenn’s house, standing today at 208 North Mountain Avenue, probably appealed to British readers because of its half-timbered work and its colors—dark clapboards and stained cypress shingles. The British usually reacted negatively to the “chilly” white so popular for framed houses. According to the contract, the cost of the residence, exclusive of interior decoration, was only $8,250. This view shows the approach to the house with the servants’ stairway to the left and the principal entrance to the right. Rarely were these two entrances placed so close to one another or the servants’ stairway so visible from the public side of a house. The far side contained a piazza and several balconies from which one could see Coney Island as well as the highlands of the Hudson River. Under the gambrel roof of the attic floor was Fenn’s studio. The sleeping floor consisted of six bedrooms, a bathroom, sewing room and linen closet. The dining room, hall and parlor were spacious rooms with wide openings between them, enabling visitors to appreciate the delicate orchestration of room colors—light salmon, cream and warm gray, respectively. Fenn decorated these rooms with objects collected during his frequent travels—white Delft and Moorish platters, Nankin blue-and-white porcelain, drawings by Burne-Jones, gilt leather from Japan, a chest dated 1639 found in a barn in England. Ficken’s career is not well documented. A native of London who was educated at Greenock Academy in Scotland, he practiced in New York City for about 50 years and died there in January, 1927. In 1883 he designed a new store for Van Tine & Co., Japanese importers, which may account for the Japanese-influenced wood-work of the Fenn house.

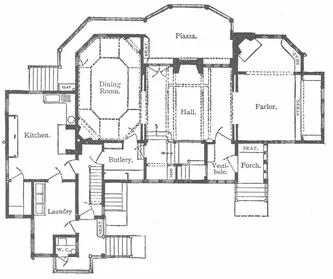

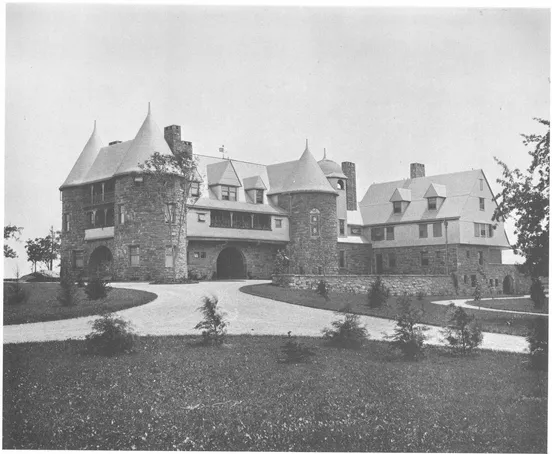

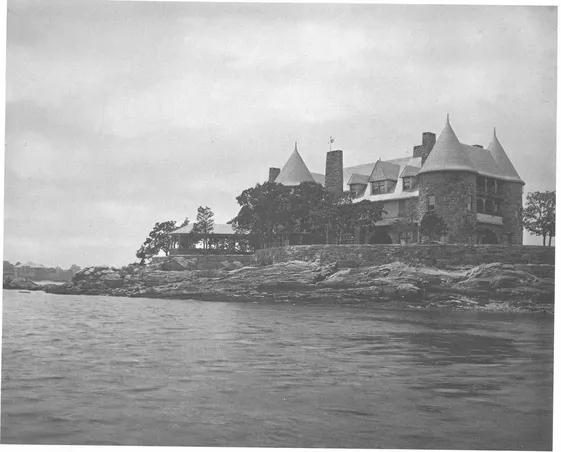

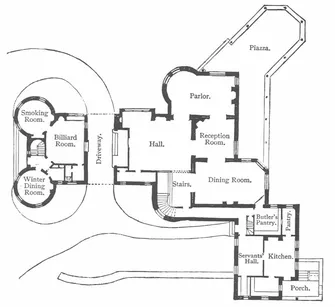

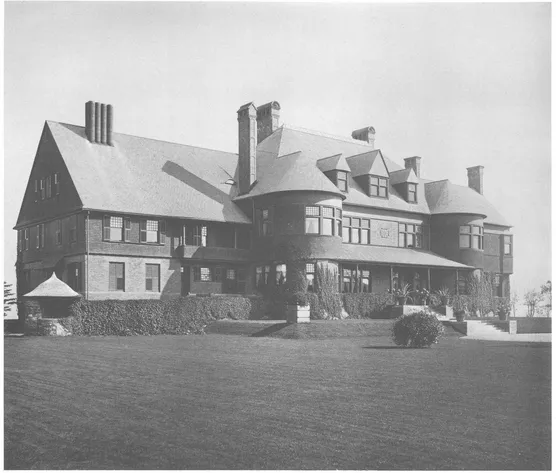

2 and 3. Charles J. Osborn residence, Mamaroneck, N.Y.; McKim, Mead & White, architects, 1885. Although there is no discernible system behind Sheldon’s arrangement of the 97 plates of houses and casinos in Artistic Country-Seats, he may have had two reasons for choosing the Osborn residence as the first to be illustrated. (See the Preface for a discussion of the original order of the Plates.) He had a weakness for huge country houses and for this one in particular; “no more magnificent private residence exists in this country than that of the late Mr. Charles J. Osborn, at Mamaroneck, on Long Island Sound.” Furthermore, it was designed by the firm of McKim, Mead & White, one of the foremost architectural offices of the 1880s, the most influential in designing houses in the period from which Sheldon made his selections, and the firm illustrated more frequently (16 times) in his anthology than any other. His open-minded outlook embraced shingled cottages as well as ostentatious mansions, but he was frequently impressed, as in this instance, by houses that were large, expensive, well furnished and functionally modern but artistically respectful of history. The length of the house facing the Sound was 153’ and its widest depth was 144’. The semirectangular main portion was 125’ × 76’, permitting principal rooms of spacious dimensions: hall (25’ x 31’), parlor (20’ × 25’), reception room (18’ x 15’), dining room (21’ x 30’), staircase hall (18’ x 12’) and billiard room (20’ x 21’). Located in the tower above the parlor, the master bedroom was 22’ in diameter with an attached dressing room (14’ x 9’). Leland Roth reported the cost of the house as $181,310, and Sheldon estimated the final bill for house, grounds, greenhouses, stables, farmer’s house and gate lodge to be approximately $400,000. As was true of the majority of the most expensive houses in this series, the percentage of the final costs spent on the woodwork and interior detail was significant. According to Sheldon, the main hall “has two stories, and is of unusual size, being . . . twenty-five feet high. Very important is the mantel-piece, two stories high, the fireplace so large that you could almost drive a horse in, and the single flue enormous. The dimensions of the fire-opening are—width, six feet; height, six feet; depth, two feet four. A wind-gauge, worked in as a part of the design of the mantel-piece, connects with the weather-vane high up on the hall-chimney outside. The paneled wainscoting has elaborate carved moldings of English oak, finished in natural color. To the left of the fireplace a wide seat, with casement-windows opening out on the Sound, and near it an ornamental niche, constitutes a striking feature.” White, responsible for the interior, generally followed contemporary practice in selecting the wood to be used in each of the main rooms. His choice of oak for the hall was not surprising. To show the social importance of both parlor and dining room, he chose white mahogany and Santo Domingo mahogany, respectively. While American parlors and dining rooms were often expensively finished, these woods were not used commonly. Painted pine was a very modest wood for White to use in the reception room. Also, its color scheme of white and gold was more delicate than one would have expected in such a ponderous dwelling. The house was also planned to be convenient and comfortable. For example, there were two hot-air furnaces and in the main basement a vegetable storage room, laundry, bathroom and the coal and wine cellars. Under the winter quarters at the west end, separated from the main body of the house by the porte-cochere, was a separate basement with a kitchen. Osborn probably used the winter quarters during the two or three days he enjoyed the house between its completion and his death in November 1885. Finally, the design owed much to history. The exterior was unusually heavy for a country house by McKim, Mead & White and its great stone towers and conical roofs intentionally recalled Norman architecture of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Vincent Scully suggested that, living there, “the client is meant to feel himself a baron.” The partnership of Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), William Rutherford Mead (1846–1928) and Stanford White (1853–1906), formed in 1879, was responsible for 785 separate commissions between that date and 1909, when McKim died. Their country houses in the period represented in Artistic Country-Seats, 1878–87, illustrate their consistent leadership in the transformation of American domestic work. So important was their role that one is tempted to see the evolution of their plans and elevations as a summary of what occurred nationally. After he entered Wall Street in 1865, Osborn became the private broker of Jay Gould and established his own firm of C. J. Osborn & Co., which survived the panic of 1873. A noted yachtsman, owner of the “Dreadnaught” and the steam yacht “Corsair,” he retired in 1883 but died before he reached 50. A fire in 1971 partially destroyed the building, now owned by the Mamaroneck Beach, Cabana and Yacht Club.

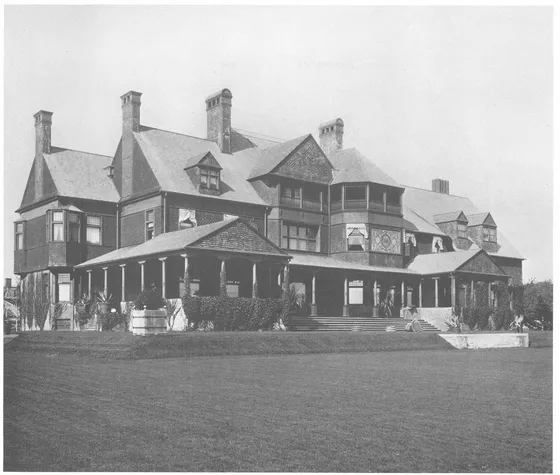

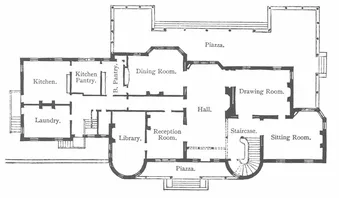

4 and 5. “Southside,” Robert Goelet residence, Newport, R.I.; McKim, Mead & White, architects, 1883–84. Still standing at the corner of Narragansett and Ochre Point Avenues, “Southside” was one of ten Newport buildings which Sheldon selected for Artistic Country-Seats, six of which were designed by McKim, Mead & White. It is a remarkable house, for its expression depends upon characteristics that are potentially contradictory—scale, elegance, wealth and self-confidence on the one hand and energy, change, vernacular complexity and informality on the other. Perhaps the public facade (above) suffers because the central symmetrical section is too high-toned and becomes detached from its supporting cast, and perhaps the quickness and lightness of the superb piazza of the oceanside (opposite) are not sustained in the middle of the upper stories, but the risks White, the principal architect, has taken have, nevertheless, produced rich results. One of the most obvious was to create one house with two distinct faces, a more formal side facing the street and a less formal side facing the ocean. Of the two, the latter is more stimulating because the appendages, which White pulled from the long quiet body of the house, look cohesive rather than adhesive, despite appearing to be lively or robust. He contrasted their physicality against the darkness, emptiness and mystery of the voids, and thus exploited the known and the unknown as well as advancing and receding sections to enrich his design. Brick was used for the first story and shingles, laid in wavy layers on the dormers and the gables of the piazza and in diamond and circle designs elsewhere, covered the walls and the roof. The rippling of these surfaces complement the activity of the forms they define. However, in 1886 Mariana van Rensselaer, a perceptive architectural critic, questioned the appropriateness of shingles for a house which was so imposing. “But there are certainly cases when, however it may be blent with other factors, the shingle seems a mistake.... For example, I think it is out of keeping both with the design and with the interior in Mr. Goelet’s house on the Newport Cliff.... Such an interior, so large, so dignified, so sumptuous and refined in decoration, is not fittingly to be sheathed in shingles. And while the design, already too heavy, too massive in effect for the place it holds, would have looked still heavier had it been executed in sterner materials, yet nevertheless as a design judged in the abstract (judged intrinsically, without reference to site and purpose and surroundings) it would, I think, have greatly been the gainer.” Designs may be judged in the abstract, but they should not be built in the abstract. The choice of shingles obviously was influenced by the spectacular natural site, by the function of the house as a summer “cottage,” and because the Goelets, confident about themselves and their social status, did not require a more substantial and expensive material.

Through the raised platform covered with grass, White integrated the house and site on both sides, but his integration was exceptionally fine on the ocean side where the rise of the lawn anticipates the steps. Recent pictures of the house, denuded of plants and ivy, make clear how important they were in reinforcing this integration. The hall unquestionably controlled the interior spatially and artistically. Sheldon’s description was very informative: “Entering the building, the spectator is at once attracted and delighted by the magnitude and the beauty of the main hall, which is forty-four feet long, thirty feet wide, and twenty-four feet high—a size very seldom seen in a villa on this side of the water—and the taste and luxury with which it has been finished and furnished are not less noteworthy. The immense chimney-piece extends two stories high, and the fireplace is large enough for a man to walk into. A gallery, supported on a series of columns and open arches, extends around the second story, and the ceiling shows the open timber-work. One of the arches forms an entrance to the main staircase; and on the other side of the fireplace is a large square opening into the parlor. Up to the line of the second story the entrance-hall is paneled solid with oak, and the balustrade of the gallery is of turned spindles of the same wood, those of the projecting balcony in the center, directly opposite the chimney-piece, being in a line slightly curving outward.” Robert Goelet (1841–1899) was a New York realtor who had inherited part of his father’s fortune, also made in New York real estate. Leland Roth reported that the house cost $83,488; Sheldon claimed $200,000, which probably included property, landscaping and interior decoration.

6. C. S. French residence, East Orange, N.J.; W. Halsey Wood, architect, n.d. This was not a summer or country house, but a suburban residence in one of the many attractive north Jersey towns which grew rapidly in the late nineteenth century. If designers of country dwellings could take advantage of unpopulated acres and delightful, if not spectacular, scenery, the city architect usually had to cope with restricted lots on a gridiron street plan. Nevertheless, architectural expression was still obligatory. In this design Wood made clear that the house must protect those who lived within. For a house to make such a statement in a community where neighbors were expected to trust neighbors was socially risky. Therefore, the architect had to include features that would counteract this antisocial impression. The curving steps made an overture to pedestrians. Though the entrance porch was dark, its arch was generously wide. The severity of the right side of the house was complemented by the activity of the left, where balconies and oriel windows provided plenty of opportunity for those within to acknowledge the neighborhood. The woodwork, in pla...

Table of contents

- DOVER BOOKS ON ARCHITECTURE

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- SHELDON AND ARTISTIC COUNTRY-SEATS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- LIST OF PLATES

- AMERICAN COUNTRY HOUSES OF THE GILDED AGE - (Sheldon’s “Artistic Country-Seats”)