![]()

GUSTAV MAHLER

1860 — 1911

LIEBST DU UM SCHÖNHEIT

This whole song should be sung with very soft and broadly sustained tones. Build it up very carefully! A song, in which the musical phrases are repeated, must, like a song with verses, be worked out with especially loving care.

The two measures which precede the song are like a question: How can you love me? What can you find in me which is worthy, worthy of your love? Perhaps you seek beauty: Oh! I am not lovely enough for you . . . Begin with a soft piano, singing with a slight hesitation: “Liebst du um Schönheit”—and answer in a quickened tempo—“o nicht mich liebe!” Go over into a broad but soft forte at “Liebe die Sonne”. Your delight over the all pervading beauty of the sun—the source of all light,—radiates through your voice. With “Liebst du um Jugend” immediately change your timbre and your facial expression. A slight resignation sounds through your voice as if you would say: “My youth is so short, it goes so quickly by. If you loved me for my youth, your love would be bounded by time”. Sing in a soft piano—“Liebe den Frühling”. In the accompaniment is an arpeggio. Like the tones of a harp, the accompanying chords are interwoven with your voice. Give it, in harmony with the accompaniment, the soft shimmer of spring’s eternal youth!

In the short interlude your thoughts ask: “What is it? For what can he love me?” Sing with a half smile: “Liebst du um Schätze?” (This question isn’t intended seriously. You know very well that he certainly can’t love you for your “riches”). Toss off this question rather playfully, giving it and “Liebe die Meerfrau, sie hat viel Perlen klar!” the romantic shimmer of a fairy tale. Now change the quality of your voice completely at “Liebst du um Liebe?” The more lightly and playfully you sing “sie hat viel Perlen klar” the more effective can you make the dark pervading warmth with which you end the song. Don’t forget the subito piano at “liebe” which again, borne with the rapture of spring by the harplike arpeggios, conveys a hesitant expectation, a humble inability to believe . . . “Liebe mich immer” should be very much emphasized—and now, breaking out into a passionate confession, you sing: “Dich lieb’ ich immerdar”. Feel in the postlude the blissful answer of the lover.

ICH BIN DER WELT ABHANDEN GEKOMMEN

Friedrich Rückert | Gustav Mahler |

Here you are a person who, of your own free will, has withdrawn from the world. You live in great peace amidst a beauty which brings you fulfillment and freedom from all desires . . . In the endless beauty of deep solitude . . .

In the prelude feel within you and all about you the peace which comes with withdrawal from the world. It is only with hesitation that your thoughts return to the world, emerging from the depths of inner contentment, free of all desire.

Begin in the softest pianissimo as in a quiet dream. Make a slight crescendo at “Welt”, in this way giving emphasis to the important word of the phrase. Sing “mit der ich sonst viele Zeit verloren” thoughtfully and with melancholy. “Sie hat so lange nichts von mir vernommen” should be sung with the utmost simplicity. Listen to the delicate flow of the interlude with an expression of contemplation. In the next phrase “Sie mag wohl glauben, ich sei gestorben” sing with a silvery quality, lightly, without expression. In the short interlude bow your head slightly, following the melody of the accompaniment. With the arpeggio chord raise your head and sing “Es ist mir auch garnichts daran gelegen, ob sie mich für gestorben hält”—thoughtfully but with a smile. Make a crescendo with a slight ritenuto at “gestorben”. Listen to the interlude which leads you from the smile of contented contemplation into the delicate parlando of the next phrase: “Ich kann auch garnichts sagen dagegen”. The realization that your seclusion is like death, like being extinguished and passing away from the world of others into the silence, makes you solemn. Sing with soft emphasis but not at all sadly—“denn wirklich bin ich gestorben der Welt”. The word “Welt” is the high point, the important idea in this phrase. Build toward this climax. Sing “wirklich” without any sentimental sliding, accenting both syllables clearly. Sing the end of the phrase in an impetuous tempo (but very discretely). The following interlude seems in the first two measures to express the hustle and bustle of the hectic world, whose echo presses in upon your solitude,—the echo of your reminiscent thoughts . . . The next three measures bring the wonderful, peaceful melody of your solitude. Sing now softly and darkly as if lost in your dreams: “Ich bin gestorben dem Weltgetümmel”, sing these words with closed eyes as if enraptured by the sound of the words, of the music, of your own voice . . . In the next phrase go over slowly from the dark cello tone into a clear and silvery piano: “und ruh’ in einem stillen Gebiet”. Clarity is all around you and within you—sunlight, the freshness and coolness of mountain heights . . . Sing with pride and with emotion: “Ich leb’ allein” and then with quiet delight—“in meinem Himmel”. Avoid most carefully any sliding or scooping in singing—“in meinem Lieben”. Sing it pianissimo—with each tone standing out clearly and with a soft purity . . . Feel the sigh of delight in the interlude, and sing with an expression of exquisite rapture: “in meinem Lieben”. End as in a prayer with warmth and blissful ecstacy—“in meinem Lied”. The word “Lied” is the climax, the conclusion, the magnificent finality. Sing it as if losing yourself in sublime beauty. Hold the expression of enchantment until the ending of the postlude.

UM MITTERNACHT

Friedrich Rückert | Gustav Mahler |

In this song the words “Um Mitternacht” are sung ten times. Immerse yourself in the meaning of the poetry and in the inexpressibly beautiful music and you will be able to sing “Um Mitternacht” with a different expression each of the ten times. I remember having sung this song once as a young beginner in Hamburg—boldly and with no real conception of it . . . After the concert I asked a distinguished musician how I had sung it. I am afraid I was quite confident of my success . . . Smiling at me, he answered: “You sang “Um Mitternacht” ten times!” . . .

The night of suffering from which this exalted song arises, is the night of decision, of destiny, of deepest resolution. Begin with a deep sadness. You are completely alone. You are Christ alone in Gethsemane, struggling, praying, feeling your loneliness as never before . . . The night which surrounds you seems silent and empty. Its sad melody flows through the song in unchanging harmony. As if in deep meditation the bass voice of the accompaniment descends slowly, step by step, this theme being repeated by the upper voice.

Begin piano with a dark timbre, with great nobility and a feeling of consecration. Your face has a searching expression,—feel the misery which is consuming you as you watch through the long hours of the night, finding no answer to your question. Sing with deep significance: “um Mitternacht hab’ ich gewacht und aufgeblickt zum Himmer”. Be careful to avoid here, as throughout the whole song, any sliding or scooping. Both the words and the music have a noble grandeur which must not be destroyed through the banality of sentimentality.

With each syllable emphasize the descent in the words “kein Stern vom Sterngewimmel” and sing a deep cello tone: “hat mir gelacht um Mitternacht”. While the vast universe lies as an open book before the eyes of Christ the God, it is locked against Christ the struggling human being, for him it is only firmament, only blue infinity . . . Tormentingly the painful question pierces through you: “How can it be, that in this hour of need, the universe is locked against me?” But there is no answer, there is only silence all about you . . . Above the worlds your searching spirit rises—as with wide spreading wings it soars upward: “Um Mitternacht hab’ ich gedacht hinaus in dunkle Schranken”—sing this with surging grandeur, with impelling force in a more flowing tempo and sing the following “Um Mitternacht” with a majestic quality. It is as if you yourself rise up, feeling: I am alone, but my solitude is noble and I have chosen it . . . I seek no further for an answer from the stars, my question reaches far beyond them to where the limitless darkness is like a final barrier, a gateway between these worlds and the great beyond—there must be an answer!

But in spite of all struggling, and searching questioning, the night remains silent and empty . . . The accompaniment rages as in tortured anxiety through your outburst of impassioned complaint: “Es hat kein Lichtgedanke mir Trost gebracht um Mitternacht”. Let this “Um Mitternacht” fall as if through tears of deepest grief.

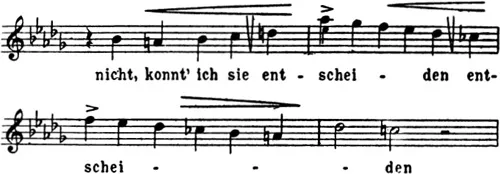

Again the desolate wastes close about you. Your thoughts now turn back to yourself, wearied of flight into the endless silence . . . Perhaps you may find the answer within your own heart—perhaps the wisdom of your heart is so great that it alone can give the answer which you seek . . . Sing as if secretly questioning: “Um Mitternacht nahm ich in acht die Schläge meines Herzens”. But no, within it is only the raging of torment and pain. There can be no answer for you: “ein einz’ger Puls des Schmerzens war angefacht um Mitternacht”. Sing this with impetuous and sombre bitterness. Your questions penetrate more deeply within you. What you now say is so great and strong that it can only be expressed with the most complete and sincere simplicty . . . Sing very simply, pianissimo, but with the majesty of the purest soul, which has dwelt within a human form: “um Mitternacht kämpft’ ich die Schlacht, o Menschheit, deiner Leiden”. Sing a warm flowing crescendo and decrescendo at “o Menschheit, deiner Leiden”. And yet you, the human Christ, do not know whether you can bear such suffering. Sing with pain and impelling power—“nicht konnt’ ich sie entscheiden mit meiner Macht um Mitternacht”. The word “entscheiden” is extended through three measures—it is important that it be sung powerfully and without being hindered by having to consider breath control. If you have difficulty in this, divide it as follows:

The melody of the night enfolds you anew: empty, silent, quiet . . . With the descent of the harmony your head is lowered. Slowly you raise it, your face transfigured through the inner realization: “um Mitternacht hab’ ich die Macht in Deine Hand gegeben”. This should be sung with mounting grandeur. From out of the night of questioning, from out of the darkness of midnight, you soar into eternal light, into the radiance of realization. Casting off the limiting chains of humanity, you become again divine—one with God, the Father, Lord of heaven and earth—“Herr! Herr über Tod und Leben, Du hältst die Wacht um Mitternacht!” Sing until the end with steadily increasing power. You must experience here the power of exalted enthusiasm which is more than vocal force.

This overwhelming song can, in my opinion, only be placed at the end of a program.

THE CYCLE

The interpretation of a cycle is, it seems to me, the ideal form of Lieder singing. Without the interruptions of applause one can with complete inner absorption maintain the tension which encloses a long series of songs. And even if the songs are absolutely different in mood and each song demands the same flexibility in changing expression as does a group of unrelated songs, still one sings a cycle within one frame. It is one fate, one life, one single chain of experience, of joys and sorrows, which, when united, seem indivisible.

This is a very great task for a singer.

Before beginning to study a cycle, immerse yourself with your whole being in the figure into which you will transform yourself, to whom you will give life with these songs. You must love this figure of your cycle, you must be one with it, be happy and sad with it, live and die with it . . .

When I mention not being interrupted by applause as an advantage, I do not mean to say anything against applause as such! Oh no: the artist needs the response of his audience, he needs confirmation, he needs the intoxication which comes with the feeling that he is understood . . . He doesn’t want to experience the exaltation of these hours alone, he wants to sense the deep communion, which comes of feeling one with his audience. He would like to take them all to his heart, knowing that they understand and like him, that they enjoy his singing as he enjoys this feeling of participation. It is applause which makes this possible.

In a cycle in order to illumine the figure whom you represent, you must explore it psychologically. Through song sketches you must portray a human being, you must build up and conclude a human fate. It requires enormous concentration to attain this goal.

Applause between the single songs would destroy the inner absorption. But so—without interruption—you hold fast within yourself as if by some magic power, that which enables you to mould creatively, through a long series of songs, a human fate. It is for you to make certain that you are not interrupted by applause: hold your listeners bound as under a spell. Stand motionless between the single songs—permit yourself no relaxation. Hold the mood of the song which you have just ended until the beginning of the following one. The intervals between the songs can only be very brief—you will soon develop an instinctive feeling as to when to pause and when to continue. When a cycle is completed, the breaking of the spell, under which you have sung it, leaves you in a state of exhaustion which seems almost unbearable. But it is the wonderful exhaustion which the creator feels when he has completed a work of art and realizes: it is good—I have given it life with my own breath—my own heart pulses through it—I have given it my own soul.

AN DIE FERNE GELIEBTE

As you begin to study “An die ferne Geliebte” you will see that the songs which the poet sings to his beloved, telling of the beauty of spring and of his love and longing for her, are set within the frame of a beautifully simple melody which in its warm and glowing flow gives them a shimmering loveliness apart from their intrinsic quality. The real inner feeling floats through the frame of this melody. Here you, the lover, tell of your yearning love. The songs themselves are like flowers which you send to your beloved who is far away. You have placed them within a lovely wreath and sent them as an expression of your devotion.

Begin with full voice and sing the first three verses in a warm floating line. Begin the fourth verse: “Will denn nichts mehr zu dir dri...