![]()

1. ORIGINS

O I’m gonna sing, gonna sing

Gonna sing all ’long the way,

O I’m gonna sing, gonna sing,

Gonna sing all ’long the way.

THE FOLK SONG of the American Negro has not experienced the long unhindered growth common to the great body of folk songs of other people. The Negro slave from Africa was introduced into a wholly alien culture and was constantly modifying and being modified by it. In this new environment it is indeed remarkable that the Negro folk song, in such a comparatively short period of development, could retain its unique racial character and become so prolific.

It is difficult to determine the period in which Negro song first assumed a definite character in America, because there were no successful attempts to collect any Negro songs before 1840 and because early letters or articles describing Negro singing were not carefully preserved.

Music played so important a part in African life that it is natural that the Negro continued his singing after reaching America. The sorrow of his enslavement probably stirred him to sing more than he did before. It is reasonable to suppose, however, that although Negroes sang, upon reaching the shores of the new country, they did not have a uniform type of song.

Assembled, as they were, from tribes of East, West and South Africa and the interior, their customs, habits, languages, and types of music were diverse. But the general interchange of slaves among the colonies and the uniformity of social conditions partially developed and fostered by Christianity welded them into a somewhat homogeneous group, from which emerged a comparatively uniform body of song. To uncover accurate descriptions and illustrations of Negro song during this period should be a valuable aid to the study of American music.

How much of the African idiom remained in the new Negro song is hard to estimate. Complete separation of the Africans from their native land, as well as separation from individuals of the same tribe, and their sudden introduction into an alien culture, brought about an inevitable interruption of African culture in America.

Opinions among authorities vary considerably regarding the amount of African culture surviving in American Negro life. Some think it negligible. Others, including Dr. Lorenzo D. Turner, who has devoted much study to this question, particularly from the standpoint of language, contend that the survivals are extensive. Without going into a detailed discussion of this matter, it is important that reference be made to African influence and survival in the American Negro’s music.

Reports of several writers present strong evidence that some African songs have persisted to this day. Edward King, in his book of Negro songs, The Great South, says :

. . . . A gentleman visitor at Port Royal is said to have been struck with the resemblance of some of the tunes sung by the watermen there to boatmen’s songs he had heard on the Nile.

Marion Holland, in her Autobiography, relates a similar coincidence in the chapter entitled “The Old African Church,” (Richmond, Virginia).

. . . . As he sat down the audience arose as one woman and broke into a funeral chant never written in any hymn book and in which the choir who sang by note took no part:

We’ll pass over Jordan

O my brothers, O my sisters

De water’s chilly and cold

But hallelujah to de Lamb,

Honor de Lamb my children,

honor de Lamb.

This was sung over and over with upraised arms. More than thirty years after the sermon of which I have written, our little party of American travellers drew back against the wall of the reported “house of Simon the Tanner” in Jaffa (the ancient Joppa) to let a funeral procession pass. The dead man borne without a coffin upon the shoulders of four gigantic Nubians was of their race. Two thirds of the crowd that trudged barefooted through the muddy streets behind the bier were of the same nationality, and as they plodded through the mire they chanted the identical wild, wailing measure familiar to me from infancy which was sung that Sunday afternoon to the words “We’ll pass over Jordan” — — even to the oft-reiterated refrain “Honor, my children, honor de Lamb.” The gutterals of the outlandish tongue were all that was unlike. The air was the same and the time and intonations.

Dr. Turner relates that he learned a song on the islands off Charleston, South Carolina, which when sung before African students at the University of London was immediately familiar to them. They actually sang the song with him.

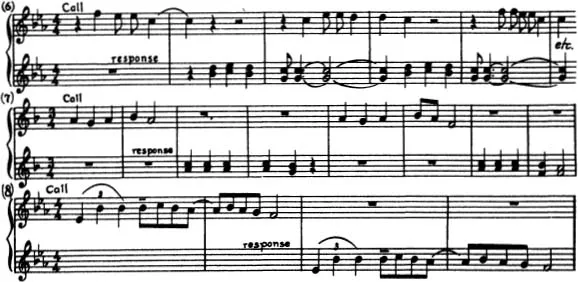

A song-form unquestionably African in origin is retained in the American Negro song. It is designated as the “call and response chant form.” The “call and response” form is interesting as well as distinctive. Its feature is a melodic fragment sung repeatedly by the chorus as an answer to the challenging lines of the leader which usually change. This melodic fragment of the chorus may comprise one word, such as “Mount Zion” in the song “On Ma Journey,” so well arranged by Mr. Edward Boatner; or a phrase, “For My Lord,” in the song “Witness,” or a sentence, “Don’t You Get Weary,” in the song “Great Camp Meeting.”

Mrs. Merlin Ennis, a missionary in Angola, Africa, describes the natives there as singing in this same style with the chorus responding with recurring lines of words to new lines by the leader.

Dr. E. M. von Hornbostel, the eminent anthropologist, in a very enlightening article, “African Negro Music,” also gives an account of the “call and response” chant form of singing by the African natives.

Henry F. Krehbiel quotes words of an African song in which every new line is answered by the line, “Oh, the broad spears.” The new lines undoubtedly were sung by a leader and the answering lines by the chorus.

The collections of songs sung by Liberian natives on phonographic recordings owned by Dr. Charles S. Johnson and of those sung by Zulu natives owned by Dr. Thomas E. Jones furnish many interesting examples of this form and add further evidence that the form is African.

It will be noticed in the following examples taken from these collections that occasionally the response is identical to the call.

The genuineness and worth of the American Negro folk song and the extent to which it represents imitation of the song which surrounded it are controversial issues. Krehbiel, in the second chapter of his book Afro-American folk Songs, has presented time-tested arguments of a most convincing nature that the Negro song in America is an original development. James Weldon Johnson, in the Preface to The Book of American Negro Spirituals, ably replies to that group of writers who disparage Negro folk-song because here and there they find traces of imitation in it! He scoffs at the idea that the Negro could have evolved “Deep River,” “I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray” and such beautiful songs from the gospel hymns he heard his white masters sing.

Dr. George Pullen Jackson of Vanderbilt University, who has devoted much time and energy to the successful development of a national appreciation of southern folk-lore, contends in his White Spirituals in Southern Uplands, one of the most commendable treatises on any phase of American folk-lore yet published, that the Negro spiritual is a copy of the white Gospel hymn. Other writers, notably Dr. Guy Johnson and Dr. Newman I. White, support this contention. Dr. Jackson has devoted two long chapters to the comparison of the tunes and texts of Negro and white spirituals. Many of the spirituals are nearly identical. In others striking similarities are revealed.

These similarities have confused most collectors of American Negro folk-song, but before they can be accepted as conclusive evidence that the Negro spiritual is an imitation of the white gospel song, several important factors must be considered. Among them are the Afro-American creative folk-genius, and the distinction between “imitation” and “re-assembling.”

The complex rhythmic schemes of the African music, which up to the present time have defied analysis or even satisfactory description by European musicians, amply provide the Afro-American with a heredity capable of creating music as imperishable as the spiritual. These rhythmic schemes are referred to with important explanation by Krehbiel, Hornbostel and Ballanta-Taylor. While the African culture per se was interrupted by the African migration to America, the musicality necessary to create significant music was not disturbed. The testing of Afro-American children for inherent musicianship by Lenoire, mentioned by Mursell and again by Kwalwasser, substantiates this assertion.

In Africa native scales were purely melodic in their concept and, apparently, were composed of tones which lacked the distinct character of rest or restlessness. There is no dispute over the fact that the Africans discarded these scales when they were introduced into the new country. But the substitution of scales and tonality can hardly be construed as imitation, especially when we attach to the term “imitation” its usual connotation. It is, rather, an incorporation of free material for a distinctive use.

It is preposterous to assume that the Negro or any other group could live in an environment rich in song, and not be influenced by it. Consequently, many of the spirituals and worksongs show traces of other songs. These musically sensitive slaves made many obvious, conscious attempts to reproduce the songs they heard around them, especially the religious songs. Often the Negro sang these songs in a manner different from that in which they were sung at the camp meetings and churches, because of his insufficient acquaintance with the words and his failure to recall them accurately. But here the attempt was to reproduce rather than to imitate. Listing these inaccurate reproductions as spirituals is the error of many collectors. This fact also explains the often too similar versions of gospel songs and spirituals.

There were, however, other attitudes toward the gospel song adopted by the Negro. One of these was an unconscious criticism of the gospel hymn, which led him to re-assemble special words or phrases of interest into a more satisfactory musical creation. He accomplished this by translating these words or phrases into idioms, adding melodic and rhythmic motives which had already been developed and widely used by the slaves. An interesting instance of this process is “Rock of Ages.” (Page 60.) The gospel hymns usually lived just a little longer than the stay of the composer-evangelist who introduced them to the community, but the spirituals were so dynamic that ...