- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Speed Mathematics Simplified

About this book

This entertaining, easy-to-follow book is ideal for anyone who works with numbers and wants to develop greater speed, ease, and accuracy in doing mathematical calculations.

In an inspiring introduction, science writer Edward Stoddard offers important suggestions for mastering an entirely new system of figuring. Without having to discard acquired information about mathematical computation, students build on the knowledge they already have, "streamline" these techniques for rapid use and then combine them with classic shortcuts.

Initially, readers learn to master a basic technique known as the Japanese "automatic" figuring method — the principle behind the abacus. This method enables users to multiply without carrying, divide with half the written work of long division, and mentally solve mathematical problems that usually require pencil and paper or a calculator. Additional chapters explain how to build speed in addition and subtraction, how to check for accuracy, master fractions, work quickly with decimals, handle percentages, and much more.

A valuable asset for people in business who work with numbers on a variety of levels, this outstanding book will also appeal to students, teachers, and anyone looking for a reliable way to improve skill and speed in doing basic arithmetic.

In an inspiring introduction, science writer Edward Stoddard offers important suggestions for mastering an entirely new system of figuring. Without having to discard acquired information about mathematical computation, students build on the knowledge they already have, "streamline" these techniques for rapid use and then combine them with classic shortcuts.

Initially, readers learn to master a basic technique known as the Japanese "automatic" figuring method — the principle behind the abacus. This method enables users to multiply without carrying, divide with half the written work of long division, and mentally solve mathematical problems that usually require pencil and paper or a calculator. Additional chapters explain how to build speed in addition and subtraction, how to check for accuracy, master fractions, work quickly with decimals, handle percentages, and much more.

A valuable asset for people in business who work with numbers on a variety of levels, this outstanding book will also appeal to students, teachers, and anyone looking for a reliable way to improve skill and speed in doing basic arithmetic.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

NUMBER SENSE

NUMBER sense is our name for a “feel” for figures—an ability to sense relationships and to visualize completely and clearly that numbers only symbolize real situations. They have no life of their own, except as a game.

Almost all of us disliked arithmetic in school. Most of us still find it a chore.

There are two main reasons for this. One is that we were usually taught the hardest, slowest way to do problems because it was the easiest way to teach. The other is that numbers often seem utterly cold, impersonal, and foreign.

W. W. Sawyer expresses it this way in his book Mathematician's Delight: “The fear of mathematics is a tradition handed down from days when the majority of teachers knew little about human nature, and nothing at all about the nature of mathematics itself. What they did teach was an imitation.”

By “imitation,” Mr. Sawyer means the parrot repetition of rules, the memorizing of addition tables or multiplication tables without understanding of the simple truths behind them.

Actually, of course, in real life we are never faced with an abstract number four. We always deal with four tomatoes, or four cats, or four dollars. It is only in order to learn how to deal conveniently with the tomatoes or the cats or the dollars that we practice with an abstract four.

In recent years, teachers of mathematics have begun to express concern about popular understanding of numbers. Some advances have been made, especially in the teaching of fractions by diagrams and by colored bars of different lengths to help students visualize the relationships.

About the problem-solving methods, however, very little has been done. Most teaching is of methods directly contrary to speed and ease with numbers.

When I coached my son in his multiplication tables a year ago, for instance, I was horrified at the way he had been instructed to recite them. I had made up some flash cards and was trying to train him to “see only the answer”—a basic technique in speed mathematics explained in the next few pages. He hesitated, obviously ill at ease. Finally he blurted out the trouble:

“They don't let me do it that way in school, Daddy,” he said. “I'm not allowed to look at 6 x 7 and just say ‘42.’ I have to say ‘six times seven is forty-two.’”

It is to be hoped that this will change soon—no fewer than three separate professional groups of mathematics teachers are re-examining current teaching methods—but meanwhile, we who went through this method of learning have to start from where we are.

Relationships

Even though arithmetic is basically useful only to serve us in dealing with solid objects, be they stocks, cows, column inches, or kilowatts, the fact that the same basic number system applies to all these things makes it possible to isolate “number” from “thing.”

This is both the beauty and—to schoolboys, at least—the terror of arithmetic. In order fully to grasp its entire application, we study it as a thing apart.

For practice purposes, at least, we forget about the tomatoes and think of the abstract concept “4” as if it had a real existence of its own. It exists at all, of course, only in the method of thinking about the tools we call “numbers” that we have slowly and painstakingly built up through thousands of years.

There is space here only to touch briefly on the intriguing results of the fact that we were born with ten fingers, and therefore use ten as a base number for our entire counting system. Other systems have been and still are used, from the binary system based on two required by digital electronic computers to the duo-decimal (dozens) base still in use in buying eggs, products by the gross, English money, inches to the foot, and hours to the day.

Our counting system is based on 10, because we have 10 fingers. As refined and perfected over the centuries, it is a wonderful system.

Everything you ever need to do in arithmetic, whether it happens to be calculating the concrete to go into a dam or making sure you aren't overcharged on a three-and-a-half pound chicken at 49½¢ a pound, can and will be done within the framework of ten.

A surprisingly helpful exercise in feeling relationships of the numbers that go into ten is to spend a few moments with the following little example.

First, look at these three dots:

Nothing very exciting yet. But now we add three more dots, right below them:

How many dots are there? Six, of course. But how did it come about that there are now six? We added three dots to the first three. Then what is three plus three?

Of course you know the answer, and of course this seems pedestrian. But there is a moral.

Did we also double the first number of dots? There were three, and we added the same number. Now there are six. So what is three plus three, again? And what is two times three?

You know the answer, but sit back for a moment and try to visualize the six dots. They are both three plus three, and two times three. The better emotional grasp of this you can get now, the more firmly you can feel as well as understand this relationship, the faster and easier the rest of the book will go.

Now we add three more dots:

How many dots?

What is three times three? Can you feel it? What is six plus three? Pause as you answer to let it sink in.

What is one-third of nine?

Play with these dots a bit. Try to see as many relationships as you can. Notice that three-ninths is equal to one-third. Why? What is six-ninths in simpler numbers?

Oddly enough, all of our arithmetic—even into the millions—is based on the number of dots you now have in front of you. Add one to nine and you have ten—which is the base of our counting system. We express it with a new one moved over to mean one ten and a zero to mean nothing—nothing more than ten.

If we really have a feel for all the relationships within the number nine, we are a long way toward feeling at home with numbers.

Stop for a bit here and, on your pad, set up ten dots. Amuse yourself by setting them up in two rows of five each. See what happens if you try to make any other number of rows with the same number of dots in each row come out to ten. Look back at the two rows of five each and see if you can feel the reason why we can express one-fifth and one-half of ten (or one) with a single-digit decimal, but not one-third or one-fourth.

Seeing Only the Answer

Beyond working at a “feel” for number relationships there are certain specific rules of procedure that will speed up your handling of numbers.

The first of these is simply a matter of training. Quite new training for many of us, and one directly contrary to the way arithmetic is often taught, but one that offers an amazing improvement all by itself.

The technique is to see only the answer.

When adding, we learn to “see” the two digits 4 and 3 as 7—not as 4 and 3.

Then, multiplying, we learn to “see” the digits 4 and 3 as 12—not as 4 and 3.

This may seem elementary. You may already be doing something very much like it in your own number handling. Yet some conscious work in this direction will pay handsome dividends.

Try to remember, if you can, how it was when you first learned to read. You spelled out each word letter by letter. It was slow and painful and not really very enjoyable. But now you grasp whole words and phrases at a glance. It's not only faster, it is easier.

This is unfortunately just the opposite to the way most arithmetic is taught, so most of us have to unlearn what was drilled into us in school. But it is well worth the effort, and it is essential to many of the streamlined methods and short cuts later in the book.

Arithmetic has been called the language of business. In many most important senses it really is, and in order to understand income-expense and financial statements you need a good grasp of it. Our insistence on the importance of seeing only the answer—of seeing 6 x 7 as 42—is basic to a vocabulary of the language. The methods and short cuts to come later might be called the grammar, but grammar is useless without vocabulary.

From time to time in this book I will slip in a little casual practice at seeing only the answer. Please do not skip these examples. They are important. They directly affect every other element in the book.

Add these numbers: 8 7 6

Did you see the digits 8, 7, and 6? You were probably taught to add “8 plus 7 is 15; 15 plus 6 is 21.”

This is too slow.

Instead, practice looking at the 8 and the 7 and thinking, automatically, “15.” Try to do this without saying or thinking either the 8 or the 7. Then, thinking only “15,” glance at the 6 and see “21.” You don't say or even think “6” at all.

If you have never tried this, the idea may be not only new but rather shocking. You can get used to it very quickly if you try, and it will speed up your number work substantially even without the other techniques. It isn't hard. It takes a bit of practice, and knowing your addition tables so you don't have to cudgel your brains to remember what 8 and 7 add up to. It's just what you do when you look at m and e and think “me” without consciously putting the two letters together.

Try it again: 8 7 6

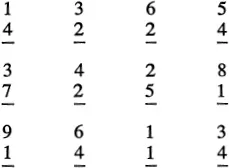

Now practice reading the following additions by seeing only the answer. Don't say to yourself, and try to avoid even thinking to yourself, the digits you are adding. Do your best to “see” 4 plus 5 as 9—not as 4 plus 5. Read the answers to these additions just as you would read i and t as it, not i and t:

If you found yourself beginning to see only the answers, very good. If not, you might find it helpful to try again.

Work With Numbers, Not Digits

The second step to developing number sense goes even further in aiding a natural and sure speed with figures. This step is far more drastic than seeing only the answer. It violates almost everything we are usually taught about numbers, yet you will quickly see how much sense it makes and how important it can be.

This rule, agreed on by almost every teacher of short-cut mathematics, i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Number Sense

- 2 Complement Addition

- 3 Building Speed in Addition

- 4 Complement Subtraction

- 5 Building Speed in Subtraction

- 6 No-Carry Multiplication

- 7 Building Speed in Multiplication

- 8 Short-Hand Division

- 9 Building Speed in Division

- 10 Accuracy: The Quick Check

- 11 Accuracy: The Back-Up Check

- 12 How To Use Short Cuts

- 13 Breakdown

- 14 Aliquots

- 15 Factors

- 16 Proportionate Change

- 17 Choosing and Combining Short Cuts

- 18 Mastering Fractions

- 19 Speed and Ease in Decimals

- 20 Handling Percentages

- 21 Business Arithmetic

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Speed Mathematics Simplified by Edward Stoddard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mathématiques & Arithmétique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.