![]()

I The Figure

Because people are interested in other people, the figure is a natural subject for art. It’s a world in itself for the sculptor to discover and explore. In the eye of the artist, the figure is a continual source of freshness and surprise.

Since the figure is so charged with human associations, we are tempted to believe that its mere use will be automatically expressive. For no matter who the artist is, or whatever his medium, the figure nearly always transmits feeling. This seems to operate even outside the province of art. Expressive references to the human figure abound in our language: the head of the bed, the foot of the hill, the arm of the law, the eye of the hurricane, etc.

Even the untrained hand, drawing the figure, is expressive. Psychological tests, based on such drawings, are said to reveal something of the emotional makeup of the subjects. This is because each of us—trained in art or not—has a personal concept of the figure and responds to it in his individual way.

But before we go a step further, we must make a sharp distinction between art and life. The figure in art is not a pseudo-person, but a man-made concept. Kenneth Clark, in his book The Nude, tells us the figure is “not a subject of art, but a form of art.” It is, he says, “an art form invented by the Greeks in the fifth century B.C., just as opera is an art form invented by the Italians” more than twenty centuries later.

The figure in art springs not from nature, but from the human mind. It differs from its flesh and blood counterpart in every respect. Structurally, the living figure has remained relatively unchanged for centuries. In art however, one change in the concept of the figure after another has been reflected by one change after another in style. In other words, while man’s body has remained essentially the same, his ideas and images of that body have been continually in flux.

As a theme of art, the figure has demonstrated its staying power by proving extensive and adaptable enough for artists throughout history to express a wide range of human feelings within its scope. How the figure will be interpreted—next by present artists or later on by future artists—we cannot predict. But we can foresee that the figure with its inherent potential and richness will retain its fascination as an art form.

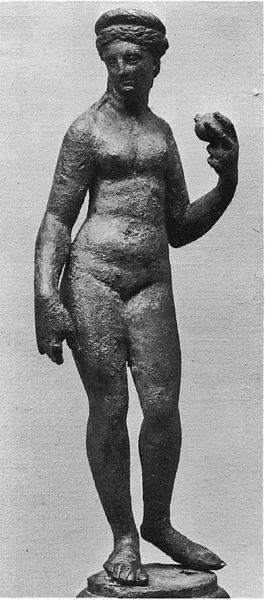

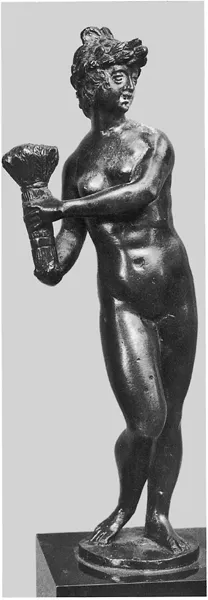

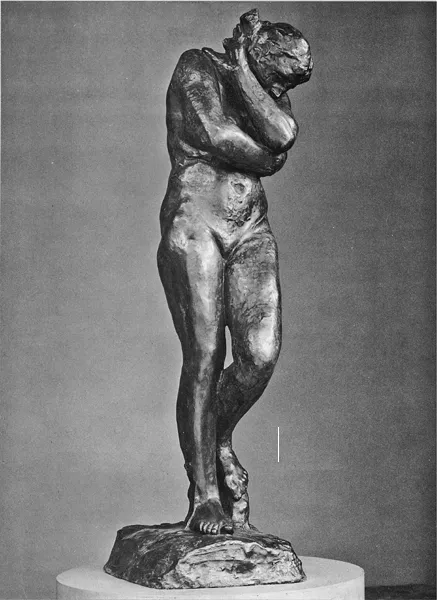

A GALLERY OF MASTER SCULPTORS

A visit to any art museum quickly demonstrates that the figure is in a class of its own. Throughout the history of art, it has appeared in many places and in many forms. On the following pages, examples of the figure are shown, covering a span of more than two thousand years. The artists who created these figures are obviously individuals of distinct backgrounds and temperaments, who together make up but a tiny sampling of the figurative tradition. Yet clearly, all are joined in a single fraternity: all are dedicated in their work to the same fascinating and persistent theme.

Greek, fourth century B.C.

Roman, third century

German, sixteenth century

Venetian, sixteenth century

Venetian, sixteenth century

French, nineteenth century

French, nineteenth century

French, nineteenth century

American, twentieth century

American, twentieth century

THE SCULPTOR’S SOURCE MATERIALS

When we select the human figure as the theme for our work, the inevitable question arises: what will our source material be? The answer is surprisingly simple. An inexhaustible supply exists. We need only glance about us. There are people of all ages to look at: men, women, and children. There are books, newspapers, and magazines overflowing with photographs. There are books on art; books on anatomy. There are works of art in parks, museums, and galleries. There is, everywhere in the world, a multitude of riches for the artist to use.

FINDING A PERSONAL STYLE

But the beginning sculptor may least appreciate the source that’s most important to him. That source is himself. Often a person becomes so intent on discovering his own personal style, he overlooks the value of what he, himself, can bring to his work. This includes not only whatever knowledge he has of art, but his total background: his life experience, training, beliefs, observations, memories, customs, and imagination. All these elements combine to become his “inner image” of the world, a kind of model against which he subconsciously measures new data.

The act of creating sculpture in itself helps us form, clarify, and expand our own inner image. As this image continues to grow and be enriched, it becomes the particular and unique character of the artist’s work. The work of Degas or Maillol, for example, can be recognized at a glance. Their styles are distinctive and personal. So are those of all great artists. Yet these styles are not contrived nor arrived at by design. They are expressions of deepest conviction and have vital meaning for the artist. One can copy the styles of others and learn from them, but the inner image we each have is unique. It may not be easy to recognize at first, but if it is allowed to grow, it will make itself felt and become clearly distinguishable from the external influences on our work.

WORKING FROM PHOTOGRAPHS OR MEMORY

The beginning sculptor can use as his sources photography, imagination, or a combination of both. Whether he works from photographs or memory, he is in effect consulting these sources in search of facts. These facts provide a starting point: they help to construct the figure, they offer general ideas about it, they also supply specific details.

When using photographs, we need to be aware of the strengths and weaknesses of this medium. Photographs are strong on gesture. They provide ideas and stimulate the imagination. But photographs are weak on form; when it comes to proportion, they can be treacherous. This is because the camera always brings various parts of the figure (which are at different distances from the lens) into a single plane. The result is then recorded as a two-dimensional image. Thus photographs tend to flatten things out, to obscure relationships and to fix the figure in a picture pattern that is essentially distorted. Photographs are most helpful when the sculptor recognizes what they can offer and what they cannot. (A source of photographs designed specifically for figure sculpture is described on page 152.)

When using photographs or memory, we should act out the gesture of the figure. Feeling the pose or position will help us extract additional facts and ideas for our work. Using a large mirror also has advantages. Since the figure means most when understood in our own terms, there is real value in studying our own physical structure. When we trust our instincts and sense of proportion, we work by conviction, not by rule. We make contact with our inner image. Our work, instead of being a copy, then becomes truly our own.

WORKING FROM LIFE

Working from a live model, whenever possible, is always best for figure sculpture. Here, however, the situation is quite different. The initial challenge is to select the pose. That pose may either be predetermined by the sculptor for some specific purpose, or taken from a natural gesture of the model.

If the sculptor chooses to invent the pose, the live model will then serve only as a point of reference and the finished work may or may not resemble the model. In this way, the sculptor can—if he wishes—create figures that hold poses which are not possible in life. He will do this by concentrating on only one part of the figure at a time: such as an arm, torso, or leg. The model must then approximate that part of the pose as well as she humanly can. The sculptor can also make his figures more “perfect” than life. He does this by using different models for different parts of the work, because each embodies for him some aspect of a “perfect” figure.

Today’s artist usually derives the pose, as well as its various elements, directly from the model. This presents him with a somewhat different set of problems. It’s sometimes difficult, when using a live model, to determine whether or not a given pose will be good for sculpture. Quite apart from the artist’s ability, a pose that seems interesting in life can lose its interest when translated into inanimate material. Some poses just do not work in sculpture. Others may result in unintentional parodies; that is, the pose, as a piece of sculpture, may take on a startling resemblance to a work from the past, or be so reminiscent of a famous museum piece as to seem a deliberate copy. Yet curiously enough, there’s no way to determine the nature of any pose unless it’s actually translated into sculptural terms. Therefore, we should always do quick three-dimensional sketches to study the poses before we devote the time and effort required to develop them into larger pieces.

The best poses are always the most na...