![]()

PART

I

1

STRINGED KEYBOARD INSTRUMENTS: THEIR ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT

Clavichord, harpsichord, piano—each is a stringed keyboard instrument, yet each instrument as it appears in various shapes and sizes possesses its own merit and strength as well as its weaknesses. A flowing melodic line is most beautifully expressed by the clavichord, whose strings are activated by gentle pressure strokes from metal tangents; but at the same time lack of tonal power limits its enjoyment to a small circle of admirers. The harpsichord, whose strings are plucked, is admirably suited to the quasi-polyphonic lines of Baroque music; however, the more lyric pieces of the early eighteenth century are less effective on the harpsichord due to its lack of flexibility in creating nuances. The piano—that dynamic instrument whose strings are struck by hammers—possesses extraordinary expressive possibilities, but lacks the clarity of the harpsichord. These three instruments, together with their more pompous companion the pipe organ, form a keyboard dynasty that remains unchallenged.

ECHIQUIER

Despite the fact that all types and sizes of early clavichords and harpsichords have been preserved, as well as information concerning their construction, the earliest stringed keyboard instrument continues to be somewhat of an enigma. In a manuscript titled Les Enseignemens (Instructions, 1483)1 Imbert Chandelier reveals his favorite pastime:

Never do I suffer from melancholy,

Incessantly I play the echiquier. . . .

What was this elusive echiquier (there are several spellings for the word) so often mentioned by the chroniclers but never clearly described? The instrument was in use at an early date, for even in Chandelier’s time it had been known for well over a hundred years. In the year 1360, King Edward III of England presented to his prisoner King Jean le Bon of France an echequier made by a certain Jehan Perrot.2 This transaction could indicate a possible English origin for the keyboard instrument, a conjecture strengthened by the poet-musician and man of the Church Guillaume de Machaut (ca. 1300–1377). In his grandiose poem La Prise d’Alexandrie (The Capture of Alexandria),3 Machaut lists an exchaquier d’Engleterre in an enumeration of musical instruments.

But there is something more to be learned about the echiquier than what is revealed in casual literary reference. Echiquier performers were in demand in their day and well paid for their services. An anonymous minstrel who played for Philippe le Hardi, Duke of Burgundy, in 1376, received a fee of six francs.4 Two years later the French poet Eustache Deschamps wrote about one Platiau who could play the echiquier as well as the harp. Deschamps himself declared that he had never undertaken anything so difficult as learning to play the echiquier.5

The French term echiquier (chessboard) was not the only name applied to this early instrument. In England it was called the chekker. In 1393 a Bishop Braybroke of London paid 3s/4 “to one playing on the chekkers at Stepney.”6 The German poet Eberhardus Cersne von Minden in Der Minnen Regelen (The Rules of Love, 1404)7 mentions not only the clavicymbolum (harpsichord) and clavichordium (clavichord) but also the Schachtbret, probably the German equivalent of the French word echiquier.

One of the few references to the instrument’s construction comes from the year 1388 when King John I of Aragon wrote to the Duke of Burgundy to request the services of the minstrel Johan dels orguens who was, according to the letter, able to play the echiquier, an instrument described as similar to the organ but which sounded by means of strings.8

Some authorities consider the echiquier to be a type of clavichord with a primitive hammer action. Others believe that it is an early ancestor of the harpsichord. To support the latter theory, it has been suggested that the sight of the jacks—the wooden pieces that housed the plucking mechanism—lined up along the keyboard could have reminded someone of chessmen, thus calling forth the name echiquier.9 Whatever the construction principle, it is obvious that stringed keyboard instruments were popular as early as the fourteenth century. Alain Chartier (ca. 1392–ca. 1430), who writes poetically about the battle of Agincourt in his Livre des Quatre Dames (Book of the Four Ladies, 1416),10 mentions the echiquier; and the Naufrage de la Pucelle (Shipwreck of the Virgin)11 by Jean Molinet (1435–1507) enumerates bons eschequiers et les doucemelles. The name echiquier, whatever it may have been, disappears from literary sources in the late fifteenth century. Public attention then turned to the clavichord.

CLAVICHORD

The clavichord is the earliest type of stringed keyboard instrument about which there is specific information available. Its known ancestry goes back to the sixth century B.C. when Pythagoras used a monochord for his experiments in musical mathematics. The monochord consisted of an oblong hollow box—the sounding board—above which stretched a string tuned by means of a peg. A movable bridge or fret made it possible to vary the length of the string. Later on, more strings were added.

Another precursor of the clavichord was the dulcimer, an instrument in which a series of strings were fitted over two stationary bridges and tuned by movable pins. The dulcimer was played by means of hammers striking the strings from above. This instrument still exists as the Hungarian cimbalom.

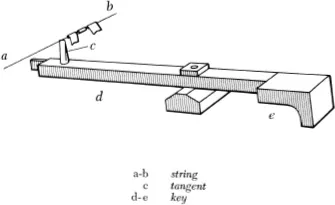

About the eleventh or twelfth century a stringed instrument was provided with a row of keys. Each key had a metal tangent at its tip (Fig. 1); when a key was struck, its tangent produced a small delicate tone capable of some dynamic variation. One string could be used for several keys, the various tangents striking a given string at different places. One of the first pictorial representations of this clavichord appears in the Weimarer Wunderbuch (Weimar Wonderbook), dated about 1440 (Ill. 1).

By the mid-fifteenth century, the clavichord competed with the echiquier for popular favor. When one Jean-Ulrich Surgant studied at the Sorbonne about the year 1472, he reported that the scholars there amused themselves by singing in parts and playing the lute or the clavichord.12 The English also liked this intimate keyboard instrument with its silvery sound. In 1477, William Horwood, master of choristers at Lincoln Cathedral, was appointed to teach the boys “playing on the clavychordes.”13 And in his satirical poem “Against a Comely Coistrown,” England’s poet laureate John Skelton (ca. 1460–1529) exclaims:

Fig. 1. Clavichord Mechanism

Reproduced by permission. Karl Geiringer. Musical Instruments. New York: Oxford University Press, 1945.

Comely he clappeth a pair of clavichordes;

He whistleth so sweetly, he maketh me to sweat;

His descant is dashed full of discordes;

A red angry man, but easy to entreat.14

Among the earliest clavichord performers are Pierre Beurse in the late fifteenth century and Henry Bredemers (1472–1522), a Flemish teacher. In Paris in 1485, the nobleman René de Lorraine paid a service fee to a performer on the manichordion (clavichord).15

The clavichord is not conspicuous in sixteenth-century records, although it was used. Scotland’s King James IV (reigned 1488–1513) entertained his bride, Margaret of England, by playing the lute and clavichord. Isabella d’Este (1474–1539), protectress of Raphael and Mantegna and known in her own time as a living example of Renaissance ideals, received clavichord lessons as a young girl. After her sister Beatrice acquired a handsome clavichord made by Lorenzo Gusnasco, Isabella ordered a similar instrument but requested a more supple keyboard.16

The so-called fretted clavichord—one string for several keys or notes—was satisfactory as long as the music itself remained simple (Ill. 2–3). However, with the advent of more complicated instrumental writing during the second half of the seventeenth century, the clavichord was gradually supplied with one string for each key and sometimes even a pair of strings for each key. Also in that century, the term clavichord cam...