- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This classic guide offers an accessible initiation into the mysteries of violin-making. Charming in its style and cultivated in its research, it covers every detail of the process, from wood selection to varnish. A fascinating history of the instrument precedes discussions of materials and construction techniques. More than 200 diagrams, engravings, and photographs complement the text.

Author Edward Heron-Allen served an apprenticeship with Georges Chanot, a preeminent nineteenth-century violin maker. The knowledge, skill, and experience Heron-Allen acquired in the master's shop are reflected in this book, which was the first to combine the history, theory, and practice of violin-making. Originally published in 1884 as Violin-Making, As It Was and Is: Being a Historical, Theoretical and Practical Treatise on the Science and Art of Violin-Making for the Use of Violin Makers and Players, Amateur and Professional, this volume has enlightened and informed generations of performers and players alike.

Author Edward Heron-Allen served an apprenticeship with Georges Chanot, a preeminent nineteenth-century violin maker. The knowledge, skill, and experience Heron-Allen acquired in the master's shop are reflected in this book, which was the first to combine the history, theory, and practice of violin-making. Originally published in 1884 as Violin-Making, As It Was and Is: Being a Historical, Theoretical and Practical Treatise on the Science and Art of Violin-Making for the Use of Violin Makers and Players, Amateur and Professional, this volume has enlightened and informed generations of performers and players alike.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Classical MusicPART I.

Historical.

DE FIDIBUS.

INTENSOS RESONA PRIMUM TESTUDINE NERVOS

MERCURIOUS FERTUR SOLLICITASSE MANU,

CUM RAPTAS PECUDES QUÆRENTEM CARMINE PHOEBUM

MOLLIVIT CREPITANS FILA CANORA LYRAE.

FLUMINA RIYORUM POTUIT CELERESQUE MORARI

THREICIUS VENTOS VOCE POETA SUÂ;

QUIN COMITES SILVAS DUXIT SCOPULOSQUE, FERASQUE

DULCISONIS DOMUIT CANTIBUS ILLE LYRÆ.

TU GENUS HUMANUM, LACRYMAS, SPES, GAUDIA, LUCTUS,

CALLIOPE CITHARÂ SUB DITIONE TENES;

GAUDIA SI TREMULIS FIDIBUS MODULARIS OVAMUS,

SIVE PLACET PLANCTUS CORDA DOLORE GEMENT;

TU MISERORUM OCULIS DULCES REVOCARE SOPORES

PECTORA TU FIDIBUS MŒSTA LEVARE QUEAS:

TU NISI SÆVORUM DOMUISTI CORDA VIRORUM

IDALII PUERI VANA SAGITTA FUIT.

S. C. G.

CHAPTER I

THE ANCESTRY OF THE VIOLIN.1

Difficulties in the Way of Research—Destruction—Errors of Description and Representation—Mention of Viols in the Bible—Bow Instruments among the Ancient Greeks and Romans—The Ravanastron—The Omerti—The Kemangeh a’gouz—The Rebab esh Sha’er—The Goudok—The Rebab—The Nofre—The Assyrian Trigonon—Pear-shaped Viols—The Rebec and the Viol —The Gigue and the Kit—The Viol-makers and their Instruments—French Claims to Invention—The Viol da Gamba—Playford—The Barytone— Prætorius—Chests of Viols.

“’Tis true, the finding of a dead horse head

Was the first invention of string instruments,

Whence rose the gitterne, viol, and the lute.”2

Was the first invention of string instruments,

Whence rose the gitterne, viol, and the lute.”2

IN no subject of research, perhaps, has the Antiquary so many difficulties to contend with as in the consideration of the “Ancestry of the Violin,” and the study of the precursors of instruments of music played with a bow.

The History of the Violin from the earliest times until comparatively recently has been one exclusively of pictures and sculptures. Metal and stone instruments may come down to us preserved in tombs, etc., in almost their original state, but the wooden instruments of music, especially those of such delicate build as those made to sustain the tension of musical strings, even had they been intentionally preserved by those whose ears they charmed, must long ere this have succumbed to the ravages of time and its attendant destroyers; besides this, any instrument played with a bow or plectrum, has the additional disadvantage that this necessary appendage may easily become separated from it and lost, whilst the instrument itself is preserved. And, indeed, this is proved by the fact, that though we know that many of the classic instruments were played with plectra of various sizes, and of various materials, some of them extremely hard and durable, in no instance has an authenticated specimen of a plectrum been found, to give us accurate information of what these prehistoric “bows” actually were. This being so, we are thrown upon descriptions in prose and verse by contemporaneous writers, on sculptures, frescoes, and carvings, and on pictures representing, or including in their subjects representations of, stringed instruments. Undoubtedly of these four the first are the best, but the inferiority of a written description to an actual representation in carving or drawing needs no comment, and we know from painful experience how intensely unsatisfactory and doubtful any such representations must be when we reflect that not only may the artist for his own artistic purposes have “invented” an instrument, so to speak, to embellish his design, regardless of the fact that he was recording, for the use of future generations, a history of the dress, manners, and instruments of his own time, but also the hand of the restorer may have been at work; and I doubt very much whether the good-natured people who subscribe heavily in cash, and get up bazaars, concerts, and what not, to raise funds for the “restoration” (save the mark !) of the parish church, with its monuments, frescoes, and ornaments, ever realize what irreparable mischief such work is apt to do, unless carefully superintended, and conscientiously and intelligently carried out by the artificers. As an instance of the first of these contingencies, I would call your attention to the well-known Holy Family, painted by Carl Müller, who is, perhaps, one of the greatest living delineators of sacred subjects. The young Mother, the carpenter Joseph, the Infant Saviour, are all breathing images whose purity of expression and truth of colouring will render the picture immortal; but, in an attitude of devotion, there kneels upon the ground an angel playing on a sort of three-stringed violoncello, more like the Kemangeh a’gouz of the modern Mohammedan (Fig. 7) than anything else. In a few centuries some Sçavant will say—“In Germany, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, was played a modification of the Mohammedan Kemangeh: it would appear to have been used exclusively for devotional purposes.” As an instance of the second of these casualties, in the lozenge-shaped panels in the roof of Peterborough Cathedral are grotesque figures playing violins (Fig. 1). Now, this roof is considered to be of the date 1194, but these violins—I use the word advisedly—are almost perfect; the f f holes, scrolls, necks, finger-boards, strings and tail-pieces show a perfection not attained till the fifteenth century, and the bows are practically those of the eighteenth century. How account for this? Simply thus—I quote the words of Messrs. Sandys and Forster3—“The ceiling was retouched a little previous to 1788, and repaired in 1835, but the greatest care was taken to retain every part, or restore it to its original condition, so that the figures, even where retouched, are in effect the same as when first painted.” This is of course impossible accurate tracings of the original designs would have been invaluable, imperfect though they might have been; but as they are, though as ornaments they may be pretty, as antiquarian records they are comparatively useless.

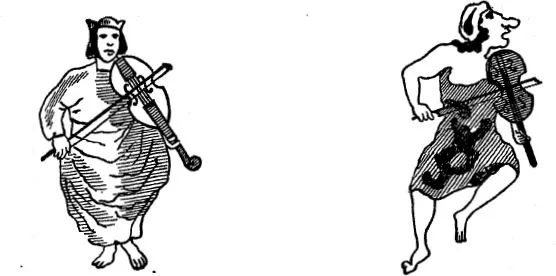

FIG. 1.—Grotesque figures from panels in the roof of Peterborough Cathedral, Date, 1194 (?).

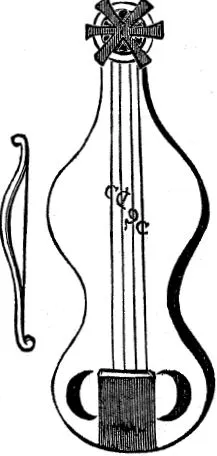

FIG. 2.—Viol attributed to Albinus (?). Fourteenth century.

A final instance that I will cite, as it concerns a frequently reproduced figure, is that of the so-called “Viol of Albinus.” This (Fig. 2) is a figure found in a MS. of the fourteenth century in the library of the University of Ghent, entitled, “De diversis monochordis, tetrachordis, pentachordis, extachordis, eptachordis, octochordis, etc., ex quibus diversa formantur instrumenta musicæ, cum figuris instrumentorum.” The manuscript is not signed, but the viol purports to be the invention of one Albinus, and until we can find out who this Albinus was, and when he lived, the figure, which is a very interesting one, is not much use. Some have stated him to be identical with a certain Alcuin, who lived in the eighth century , but the viol is not only of a very fourteenth century shape, but its four strings are actually marked A, D, G, C, which renders it absurd to suppose it is a faithful representation of an eighth century viol. Others, more enthusiastic still (reminding us of Rousseau and Bartoloccius cited below), try to identify him with the Albinus mentioned by Cassiodorus (!), but the reader who peruses the next few pages will quickly dismiss any idea of this sort. No; this remains one of those mysteries which we can only solve by analogy, and therefore, as we cannot identify Albinus, and the MS. is obviously fourteenth century, and appearances favour the assumption, we can almost safely say that we have here a fairly well-developed viol of the fourteenth century, represented with its mode of tuning and bow complete.

These three instances out of countless examples are enough to show the difficulties with which I enter upon a notice of the earliest forms of the fiddle. Plato,4 indeed, tells us that among the ancient Romans “it was not allowed to painters or other imitative artists to innovate, or invent any form different from what were established, nor lawful, either in painting, statuary, or music, to make any alteration.” This rule would, indeed, have been most useful if it had been adhered to throughout all ages, and would relieve the musical antiquary from the necessity of making my first complaint; but the ravaging restorer would still rage around among the monumenta temporis acti, and nullify this far-seeing and provident law. It is to such meagre materials, therefore, that I turn for the information to be set forth at this present. Even later on in the Middle Ages, as will be seen, the sources of information are equally unsatisfactory; and in concluding these preliminary remarks, for the length of which I must crave your indulgence, I merely quote Bottée de Toulmont,5 who says—“Si le moyen âge est l’époque où la nomenclature des instruments est la plus nombreuse, c’est aussi celle où les renseigneme...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- “Forewords”

- Dedication

- Poem (Percy Reeve)

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- “Echoes ” (R. A.)

- Introduction

- Part I.—historical.

- Part II.— Theoretical

- Part III—Practical.

- Appendices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Violin-Making by Edward Heron-Allen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Classical Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.