![]()

CHAPTER I

THE MODERN PIANO

The possibilities of the piano have been a matter of continual development. The highly developed instrument of today is the descendant of many attempts at perfection. When Bartolomeo Cristofori, in the early years of the eighteenth century, sought to improve the keyboard instruments he was manufacturing, he found that it was necessary to start out upon an entirely new line of attack. The instruments of the time (clavicembali, harpsichords, etc.) were limited in expression because the wires were plucked with quills, much as a zither is played. By inventing an instrument in which the wires were struck with hammers, instead of being plucked, he made a distinct departure. He called it the Forte-Piano, because it could play both loud and soft. Later, doubtless for euphony, it became the pianoforte, and then the piano. But it could do far more than play loud or soft. It permitted the production of different classes of sound quality within its range. These are controlled by touch; and it is because of this that one of the basic problems of its use is the matter of touch, with which we shall have a great deal to do in this series. Rubinstein called the pedal “the soul of the piano.” But the pedal can be used like a soul in purgatory or like one in paradise. The finest pedaling in the world, however, is worthless unless the student is familiar with the basic principles of touch.

Before entering the discussion of the matter of touch or technic, however, let us consider first of all the most important thing, a good foundation in real musicianship. Certain things cannot be skipped in the early lessons without appearing to the enormous disadvantage of the student in later years. Possibly here is the greatest waste in music teaching, poor or careless instruction in the earlier years. The teacher of beginners is a person of great importance in all education, particularly in music. In Russia the teacher of the beginners is often a man or a woman of real distinction. The work is not looked upon as an ignoble one, worthy of only the failures or the inferior teacher. These teachers are well paid. Of course, in America you are developing many teachers of beginners who have had real professional training for this work; but in the past there must have been some ridiculously bad teachers of elementary work, judging from a few of the so-called advanced pupils whom I have been called upon to teach.

The folly of paying a teacher a considerable fee for instruction that should have been given at the very beginning, is too obvious to comment upon. Surely a practical people like the Americans will rectify this.

THINGS THAT CANNOT BE SKIPPED

A complete knowledge of notation should be drilled into the pupil at the first lesson. It is all very well to sugar coat the pill for the lively American child; but the musical doctor must see that there is no needed ingredient left out of the musical pill.

The pupil, for instance, must know all about notes. He must be able to identify instantly the time value of any given note, its name on, above or below the staff. When I first came to America, seventeen years ago, I gave some lessons. I find now that in the interim, there has been a great advance in methods of early instruction in America; but many students still indicate the most superficial early training.

INDIFFERENCE TO RESTS

One indication of this is the indifference to rests. Rests are just as important as notes. Music is painted upon a canvas of silence. Mozart used to say, “Silence is the greatest effect in music.” The student, however, does not realize the great artistic value of silence. The virtuoso whose existence depends upon moving great audiences by musical values knows that rests are of vital importance. Very often the effect of the rest is even greater than that of the notes. It serves to attract and to prepare the mind. Rests have powerful dramatic effect. Chaliapin has an instinctive appreciation of rests; and any one who has heard the great Russian’s recitals knows that his rests are often as impressive as the tones of his gorgeous voice. Indeed, poise in music is often largely a matter of the correct observance of the full value of rests.

Sometimes it takes courage, seemingly, for the student to value a rest properly. He has the feeling that the audience is impatient and that he must go on playing. There must be sound. The composer, in creating the composition, did it with a distinct design in mind. That is the element of balance and symmetry which is natural to art. The student who plays a half rest with the value of a quarter rest destroys this artistic symmetry. The audience unconsciously feels this, and the work of the student does not please.

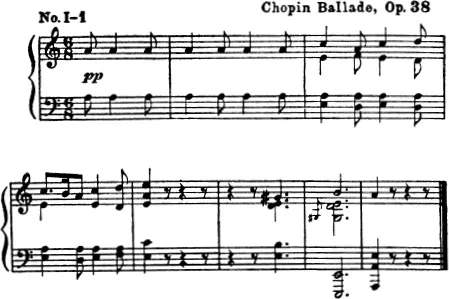

Examples I-1 and I-2 may be cited as examples of the dramatic value of rests. The first is from the F Major Ballade of Chopin. Hurry over this rest at the end of the composition and the value of a beautiful art work is destroyed.

The second example is from the Chopin Nocturne No. 13 in C Minor. Here the rests are in the right hand. “But the left hand continues to play,” you say. Of course, but nevertheless you must feel the rests. If you were singing this beautiful melody, or playing it upon the flute or the violin, you would have to feel the rests. I don't know what it is; but when you have that feeling in your mind you will bring it out in your playing, and your playing will be correspondingly more beautiful. There are thousands of passages of similar intent, in different pieces.

One remedy is to imagine the melody as heard from an instrument of different quality from the piano—say the oboe, or the French horn. Another remedy is to play each hand alone, strictly observing the time and feeling the rests. This excerpt from Chopin makes a most excellent example; and the pupil who practices it religiously for a little while will gain a new respect for rests.

The reader is probably surprised by this time that I have taken up so much time with something that is not music at all, but silence. Well, it is upon such “little” things that all really important artistic progress must be based. Take the matter of note alterations. There are really three forms of staccato; but the average careless student either does not know about them or he plays all forms in the same identical manner.

The first form with the point

is the shortest. This might be represented as cutting off three-fourths of the value of the note and leaving only one-quarter, thus:

The second form is the dot:

which cuts the note in half, thus:

The third form is the dot and the dash,

which slices off only one-quarter of the note and leaves three-quarters to be played, thus:

This touch is sometimes called portamento; and it has a very distinct and important effect. These conceptions are general. They must not be taken too literally.

DEVELOPING RHYTHM

Before leaving these elements of musicianship, I feel it incumbent to point to the need for a fine development of rhythm. American students are capable of wonderful rhythmic development; but they have been limited in their opportunities. They hear jazz and ragtime from morning to night, and come to learn one rhythm and one rhythm only. They should be taught, early in life, all sorts of rhythmic designs. They should be taught that the rhythm must remain, although the moods may vary the rapidity of the tempo. They should be taught to develop a rhythmic sense like the Gypsies.

It is very hard to teach rhythm. It must be felt. It is contagious to a certain extent; and for that reason the student who attends concerts and who hears fine rhythms upon the various mechanical sound-reproducing machines has distinct advantages.

Duet playing, with a strong, vigorous musical individual...