CHAPTER 1

The Limits of U.S. Territorial Expansion

Robbery by European nations of each other’s territories has never been a sin, is not a sin today.

To the several cabinets the several political establishments of the world are clotheslines; and a large part of the official duty of these cabinets is to keep an eye on each other’s wash and grab what they can of it as opportunity offers.

All the territorial possessions of all the political establishments in the earth—including America, of course—consist of pilferings from other people’s wash.

Mark Twain, 1897

Why did the United States stop annexing territory? Mark Twain’s country was ten times larger than the colonies that declared independence in 1776, the result of expansionism by Thomas Jefferson, James Polk, William Henry Seward, and countless other U.S. leaders.1 Yet since Twain’s death in 1910 the United States has made no major annexations. Political scientists and historians alike have highlighted the U.S. shift from territorial expansion to commercial expansion, arguing that transformations in the sources of economic wealth and military power undercut the profitability of further annexations after the mid-nineteenth century. However, this conventional wisdom overstates the importance of material constraints on U.S. expansionism and neglects the main reason U.S. leaders rejected the annexation of their remaining neighbors: its domestic political and normative consequences.

By absorbing external territory into the state, annexation necessarily changes the state. Some of those changes are positive—for example, increasing its future wealth and security by gaining natural resources and population or controlling strategic terrain. These potential benefits may stoke leaders’ expansionist ambitions. Yet annexation may also change the state in ways that leaders consider negative—for example, distorting its institutions and demographics in ways that undercut their domestic political influence or their normative goals for the state. Even opportunities to pursue annexation that appear profitable in material terms may be undesirable for leaders who fear these domestic costs.

Two factors made the presidents, secretaries, and congressmen who shaped U.S. foreign policy during the nineteenth century especially sensitive to annexation’s domestic costs: democracy and xenophobia. First, they were acutely aware that their democratic institutions left them vulnerable to domestic political shifts resulting from the assimilation of new populations or the admission of new states. At the same time, they valued those democratic institutions enough to grant all major territorial acquisitions an eventual path to statehood, rejecting endless imperialism and militarized rule as threats to democracy at home (at least until 1898). Second, their xenophobia fueled widespread opinions of neighboring peoples as undesirable candidates for U.S. citizenship. As a result, virtually all viewed large foreign populations as deterrents, sources of moral and cultural corruption that would degrade the United States and undermine the popular sovereignty of their existing constituents if annexed.

Together, democracy and xenophobia raised the potential for annexation to impose formidable domestic costs from the moment the Constitution was ratified. This notion—that the factors most profoundly limiting U.S. territorial expansion were in place from the earliest days of the Union—is a provocative one. After all, scholars usually search for the cause of some effect by asking what else changed when that effect appeared. Most previous studies have followed this approach, explaining the end of U.S. annexation by asking what else changed by the late nineteenth century and identifying economic changes like industrialization and globalization or military transformations like nationalism and regional hegemony as the most likely culprits.

Yet in this case it turns out that the answer was present all along: the U.S. pursuit of annexation came to an end not because of any new development but because an old process had run its course. U.S. leaders did not fundamentally change their expansionist calculus in the mid-nineteenth century; rather, they confronted the prospect of annexing neighboring territories episodically as opportunities arose, deciding whether or not to pursue each specific territory based on its material, political, and normative merits. Once they had rejected a neighboring territory, their successors rarely reversed that decision, and one by one each remaining neighbor was either annexed or understood to be better left independent.

In this way U.S. leaders pursued annexation throughout the nineteenth century by picking and choosing from among their potential options until they ran out of desirable targets. Congressional majorities supported presidential efforts to annex areas like Louisiana and California, but they delayed similar efforts in Florida and Texas and defeated efforts to gain more of Mexico and Cuba. Time and again they raised objections to the domestic costs of annexation, and as they crossed their remaining neighbors off their list of viable targets, the practice gradually disappeared from U.S. foreign policy. To recognize that annexation has domestic consequences and that those consequences bear on leaders’ decision making is to recognize that in international politics, as in the human diet, you are what you eat. And the United States has always been a picky eater.

What Is Annexation?

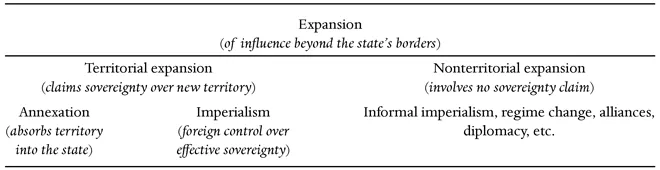

Like many terms, “annexation” has often been used in vague and contradictory ways. In this book, consistent with its dictionary definition, annexation refers to the absorption of territory into a state. The most straightforward way to think about annexation is as a subset of territorial expansion, which is itself a subset of the expansion of international influence (table 1.1). Expansionism, or states’ pursuit of influence abroad, has attracted consistent interest from international security scholars due to its role in causing wars and shaping the international system.2 While most forms of expansionism simply aim to increase one state’s leverage over another’s policies, territorial expansion sees a state claim Westphalian sovereignty over an area beyond its previous borders, declaring itself to be the highest political authority there and proscribing foreign interventions.3 Territorial expansion may increase the state’s economic and military power more efficiently than other forms of expansionism—depending on its administrative and technological abilities to utilize its new territory—which explains why it is simultaneously a coveted foreign policy goal and a potent source of international conflict.4

Territorial expansion, in turn, comes in two forms, annexation and imperialism, distinguished by whether the state fully absorbs its new territory or rules it separately and subordinately. A state in international relations, as opposed to U.S. states, is an institutional order that exercises paramount political authority and a monopoly on legitimate violence within its borders.5 Annexation expands that order by integrating new territory within its core protective, extractive, and legislative institutions. This doesn’t mean that states are internally homogeneous—no state entirely is—but rather that a state’s relationship with the annexed territory comes to mirror its relationship with its other constituent territories. By merging the new territory into the state itself, annexation enables leaders to redefine their national homeland, molding local identities, institutions, and cultural politics to reduce the likelihood of future unrest and maximize deterrent credibility in the eyes of international rivals who might desire to gain that territory for themselves.6

Table 1.1 Forms of international expansion

In contrast, imperialism establishes “foreign control over effective sovereignty,” in Michael Doyle’s phrasing.7 It too involves a new sovereignty claim, but the state rules its empire externally through institutions separate from and subordinate to those governing itself. Imperialism thus represents a state’s deepest method of expanding its influence abroad without expanding the institutional order that defines the state itself. Like nonterritorial forms of expansionism, imperialism may function as a precursor to annexation. For example, the United States pursued diplomacy, economic and cultural penetration, regime change, and imperialism in Hawaii before annexing it. But leaders may also pursue imperialism without any intention to annex territory. Those primarily concerned with extracting resources from a territory may prefer imposing institutions designed to streamline that process via imperialism rather than extending their state’s more cumbersome legal institutions via annexation. Similarly, leaders whose authority depends on ethnic nationalism may prefer to subordinate areas inhabited by other ethnicities via imperialism rather than compromise the perceived purity of their nation by annexing them.

Distinguishing between annexation and imperialism is crucial to understanding why the United States lost its early appetite for territorial expansion. U.S. leaders tended to think of territorial expansion and annexation as one and the same, imperialism being valid only on a transitional basis to prepare territories for integration into the Union. Leading a country born through anti-imperial revolution and infused with liberal ideology, they widely assumed that any territories they acquired would eventually gain representation either by enlarging existing states within the Union or, as quickly became the norm, by admitting new states to the Union. Most leaders rejected the notion of perpetual imperialism as fundamentally incompatible with American democracy. It emerged as a serious proposition during their debates only when there was widespread agreement that potential statehood was unthinkable, notably with regard to southern Mexico in 1848 and the Philippines in 1898. In other words, when U.S. policymakers considered opportunities for territorial expansion, they considered them first and foremost as opportunities for annexation.

This book seeks to explain why U.S. leaders pursued annexation when and where they did, not why their efforts succeeded or failed. Since annexation extends a state’s institutional order over new territory, it cannot occur without conscious implementation by state leaders. There are no accidental annexations. Unlike a balance of power, which may persist for centuries despite great powers’ frequent attempts to overturn it and dominate each other, the pursuit of annexation is necessary for its occurrence.8 Explaining why the United States stopped pursuing annexation can therefore tell us why it stopped annexing territory.

U.S. foreign policy today continues to feature other forms of expansionism, including diplomacy, foreign aid, sanctions, military occupation, regime change, and (in a mostly informal way) imperialism. Its military reaches all corners of the globe, yet the U.S. domestic political system remains limited to part of North America, seemingly invalidating Joseph Stalin’s mantra that “everyone imposes his own system as far as his army can reach.”9 For all their rhetoric about creating an “empire of liberty” and fulfilling their “manifest destiny,” U.S. leaders annexed far less territory than was feared by neighbors who quaked before the “northern colossus” and European leaders who assumed that further U.S. territorial expansion was “written in the Book of Fate.”10 Why did U.S. leaders stop pursuing annexation?

Why Abandoning Annexation Matters

The reasons why the United States stopped pursuing annexation should interest scholars and students of international relations, diplomatic history, American history, and American politics as well as members of the broader international public. By choosing to pursue only the territories they did, U.S. leaders contradicted typical patterns of great power behavior throughout history, offering intriguing puzzles to theories of international politics. Moreover, their decisions fundamentally shaped the geopolitical, economic, demographic, institutional, and ideological development of the United States across the centuries that followed, with repercussions that continue to echo through its current flaws and virtues. Finally, their rejection of further annexations enabled the creation of the modern international order, and understanding why they did so can help us understand why that order looks the way it does and how long we should expect it to last.

U.S. territorial pursuits differed from typical great power behavior in two major ways: (1) by targeting land rather than people, and (2) by declining as U.S. power grew. Most great powers in history have spent their blood and treasure trying to absorb nearby population centers and their workforces, which could be taxed and conscripted, rather than uninhabited lands requiring extensive settlement in order to yield a profit.11 They did so with good reason, since population and wealth are the building blocks of military might. Yet U.S. leaders preferred to annex sparsely populated lands like Louisiana and California, expelling many of the inhabitants they found there. Moreover, they intentionally declined opportunities to absorb population centers in eastern Canada, southern Mexico, and the Caribbean despite the impressive material benefits those territories offered. In short, when the United States pursued annexation, its choice of targets reversed the usual great power appetite.

U.S. leaders also broke from historical precedent by abandoning territorial ambitions as their power grew. International politics used to be defined by a quest for conquest: from Alexander and Qin Shi Huang to Genghis Khan and Napoleon, the list of historical conquerors “could go on almost ad infinitum.”12 Those leaders saw increases in their own power as opportunities to conquer and absorb their neighbors, making history trend “toward greater accumulation and concentration.”13 The United States helped reverse that trend, rejecting further annexations even as it rose toward an unprecedented position of global unipolarity. Robert Gilpin’s maxim that “as the power of a state increases, it seeks to extend its territorial control” may hold true for the United States if broadly conceived to include spheres of influence and alliances, but it is squarely defied by the ...