This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This fascinating anthology commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Civil War with heartfelt letters by Union and Confederate sympathizers and soldiers of all ranks. Authentic illustrations accompany insightful missives by Lincoln, several generals (including Grant, Lee, Butler, Jackson, and Sherman), Walt Whitman, Jefferson Davis, and many of their contemporaries.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Civil War Letters by Bob Blaisdell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1863

WOUNDED: “I ran around till my boot was full of blood”

Private Dwight A. Lincoln

42nd Illinois Volunteers

Nashville, Tennessee

January 10, 1863

42nd Illinois Volunteers

Nashville, Tennessee

January 10, 1863

Dear Father—

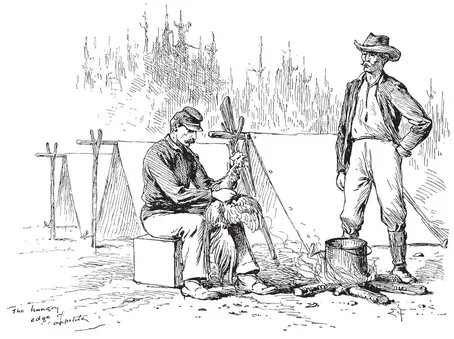

I received your kind letter at Nashville, after having marched all day through cornfields and mud, expecting to have a fight every moment; but lo and behold, the enemy were gone, and we went into camp, wet through and nothing scarcely to eat. But the next day we had an abundance. The next day we started for Murfreesboro, and arrived at night as near there as we thought it healthy to go. But we were not allowed to have any fire, so we had to make a supper of a few pieces of crackers. The next morning we got up all wet, it having rained in the night. We ate what we had left in our haversacks, and started our brigade in advance.

We did not go more than a mile before we were stopped by the enemy. Our regiment was thrown out as skirmishers. We “skirmished” most of the day. Night came, and not having had any dinner, we had nothing for supper. A hog made his appearance, and we soon dispatched him. We had no time to cook it before we were called to go on picket. We went; lay on the ground four hours; and liked to have shook ourselves to death with cold; came back to the reserves, cooked some meat and ate it, and then lay down till morning.

In the morning we were relieved, and took our position in line of battle, when some meat and mush were brought up. We had hardly time to eat it before we were called on to make a charge on the enemy. We started, and had only gone a short distance before a man, who stood beside me in the ranks, was shot dead. On we went, the boys cheering, and the enemy peppering us and falling back. We drove them, and regained our old ground, which was covered by dead and wounded. Just at this time the men on our right gave way; so of course we had to retreat. In the charge, which was made across an open field, we had five wounded and one killed. The fighting after this was terrific. Our division was at one time surrounded on three sides. It was about this time that I was wounded. Colonel Roberts was shot dead a few paces behind me. I ran around till my boot was full of blood, and saw it was no use, so I lay down and was taken prisoner. I was held four days, during which time I had two small biscuits a day to eat, and it was over a day before my wound was looked to or washed. I am wounded in the left knee, the bone being a little shattered. It is a pretty bad wound, but I guess it will heal if nothing befalls it. If the ball had struck an inch and a half higher, it would have been all day with me. The brigade doctor said it was as narrow an escape as I would ever have.

The rebels forgot to parole the wounded in the tent I was in, so I am not paroled. Much love to all.

From your son,

DWIGHT A. LINCOLN

DWIGHT A. LINCOLN

Private Lincoln died ten days later in a Nashville hospital.

Source: [SL]

BATTLE OF STONE RIVER: “more lives were lost in two hours there, than in the same time during the war”

W. H. Timberlake, U.S.A.

81st Regiment, Indiana Volunteers

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

January 12, 1863

81st Regiment, Indiana Volunteers

Murfreesboro, Tennessee

January 12, 1863

To [Unknown]—

We had a desperate battle here. For four days the fortunes of war seemed to be against us, but Providence at last turned the scales in our favor. I can yet seem to hear the din of the conflict—the whiz of the bullet, the scream, of the shell, and the roar of the artillery! It is yet with me like one who has been on the sea; he becomes so accustomed to the roll and pitch of the ship, that it seems when on shore that the very earth is upheaving beneath his tread.

Our regiment was in the commencement of the bloody battle of Wednesday (December 31st), when our right was turned. General Jefferson C. Davis commands the division, and we stood the full shock of their concentrated charge.

General Johnson, who commanded a division adjoining us, suffered himself to be surprised and routed, thereby very nearly losing us the battle and causing the army to be annihilated. It seemed as if all were lost on that Wednesday. The enemy having massed their forces, or nearly all their whole force, against our right wing, commanded by McCook, swept over it like an avalanche! There was no resisting it. Our brigade gained more honor than any other on the right; but we had to fall back, leaving killed and wounded in their hands. Everything went against us that day, and nearly everyone prayed for night to come, that we might retreat. But Rosecrans knows no such word.

Thursday.—No advantage on either side, but the carnage terrible! Friday.—The battle commenced at two o’clock, and I venture to say more lives were lost in two hours there, than in the same time during the war. The enemy attacked our left wing, which resisted stubbornly, but, like ourselves, had to fall back from loss of numbers, but not until they had made sad havoc among the enemy.

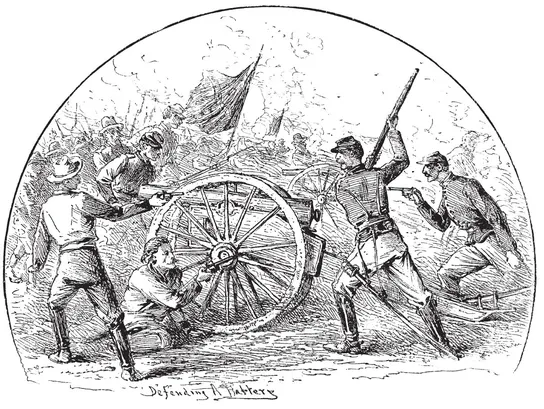

As they fell back, General Negley threw his division forward, while our artillery was concentrated against their ranks. Then the rebels lost; they were literally mowed down! They had such an immense force, however, that Negley could not drive them. His men and the rebels were very much disorganized in the hand to hand conflict, when orders were brought to our general to “forward with his division, and make a charge!”

Away we went, “double-quick,” or rather, “on the run”; forded a stream over knee-deep three times; charged up the hill, where the rebels were, with a yell, and the rebs, panic-stricken, threw away their arms and fled. Such a sight as we saw! The ground was covered with the dead and dying.

The rebels admitted their loss in that one charge to be 800! This was the decisive blow of the battle. That night they commenced their retreat. But, in the four days’ fight, with two days of heavy rain, cold, without blankets, no fires, and scarcely any sleep, our forces were entirely too exhausted to pursue.

How near we came to being defeated, only those who saw can realize.

Source: [SL]

DOUBT: “I now lament extremely my early education and life”

Captain Charles Francis Adams, Jr., U.S.A.

First Massachusetts Volunteer Cavalry

Potomac River, Virginia

January 23, 1863

First Massachusetts Volunteer Cavalry

Potomac River, Virginia

January 23, 1863

To His Brother, Henry Adams

I do wish you took a little more healthy view of life. You say “whether my present course of life is profitable or not I am very sure yours is not.” Now, my dear fellow, speak for yourself. Your life may be unprofitable to you, and if it is, I shall have my own ideas as to why it is so; but I shall not believe it is until I see it from my own observation. As to me my present conviction is that my life is a good one for me to live, and I think your judgment will jump with mine when next we meet. I can’t tell how you feel about yourself, but I can how I feel about myself, and I assure you I have the instinct of growth since I entered the army. I feel within myself that I am more of a man and a better man than I ever was before, and I see in the behavior of those around me and in the faces of my friends, that I am a better fellow. I am nearer other men than I ever was before, and the contact makes me more human. I am on better terms with my brother men and they with me. You may say that my mind is lying fallow all this time. Perhaps, but after all the body has other functions than to carry round the head, and a few years’ quiet will hardly injure a mind warped, as I sometimes suspect mine was, in time past by the too constant and close inspection of print.

I never should have suspected it in time past, but to my surprise I find this rough, hard life, a life to me good in itself. After being a regular, quiet respectable stay-at-home body in my youth, lo! at twenty-seven I have discovered that I never knew myself and that nature meant me for a Bohemian—a vagabond. I am growing and developing here daily, but in such strange directions. Let not my father try to tempt me back into my office and the routine of business, which now seems to sit like a terrible incubus on my past. No! he must make up his mind to that. I hope my late letters have paved the way to this conviction with him. If not, you may as well break it to him gently; but the truth is that going back to Boston and its old treadmill is one of the aspects of the future from which my mind fairly revolts. With the war the occupation of this Othello’s gone, and I must hit on a new one. I don’t trouble myself much about the future, for I fear the war will not be over for years to come. Of course I don’t mean this war, in its present form: that we all see is fast drawing to a close; but indications all around point out to me a troubled future in which the army will play an important part for good or evil, and needs to be influenced accordingly. I shall cast my fate in with the army and the moment reorganization takes place on the return of peace and the disbandment of volunteers I shall do all I can to procure the highest grade in the new army for which I can entertain any hope.

I now lament extremely my early education and life. I would I had been sent to boarding school and made to go into the world and mix with men more than my nature then inclined me to. I would I had been a venturous, restive, pugnacious little blackguard, causing my pa-r-i-ents much mental anxiety. In that case I should now be an officer not at all such as I am. But after all it isn’t too late to mend and enough active service may supply my deficiencies of education still. Meanwhile here I am, and here I am contented to remain. The furlough fever has broken out in our regiment, and the officers, right and left, are figuring up how they can get home for a time. Three only of us are untouched and declare that we wouldn’t go home if we could, and the three are Greely Curtis, Henry Higginson and myself. Our tents and the regimental lines have become our homes. . . .

I’ve all along told you, you ought to remain in London, and I say so still; for that is your post and, pleasant or unpleasant there you should remain. I have told you all along, however, that I didn’t like the tone of your letters. Your mind has become morbid and is in a bad way—for yourself—both for the mens sana and corpus sanum. A year of this life would be most advantageous. Your mind might rest and your body would harden. My advice to you is to wait until you can honorably leave your post and then make a bolt into the wilderness, go to sea before the mast, volunteer for a campaign in Italy, or do anything singularly foolish and exposing you to uncalled for hardship. You may think my advice absurd and never return to it again. I tell you I know you and I have tried the experiment on myself, and I here suggest what you most need, and what you will never be a man without. If you joined an expedition to the North pole you might not discover that terra incognita, but you would discover many facts about yourself which would amply repay you the trouble you had had. All a man’s life is not meant for books, or for travel in Europe. Turn round and give a year to something new, such as I have suggested, and if you are thought singular you will find yourself wise.

Tuesday, 26th. I suppose you in London think it strange that I do not oftener refer to the war in my letters and discuss movements. The truth is that you probably know far more of what is going on than I do, who rarely see papers, still more rarely go beyond the regimental lines and almost never meet any one possessed of any reliable information. As a rule, so far as my knowledge goes, the letters of correspondents of the press are very delusive. They get their information from newspaper generals and their staffs and rarely tell what they see. Now and then, very rarely, I see a plain, true, outspoken letter of an evident eyewitness. . . .

I have given up philosophising and do not often, except in very muddy weather indulge in lamentation. I think indeed you in London will all bear witness that my letters, under tolerably adverse circumstances, have been reasonably cheerful, and I hope they will remain so, even if the day...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Note

- 1861

- 1862

- 1863

- 1864

- 1865

- Sources