- 672 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

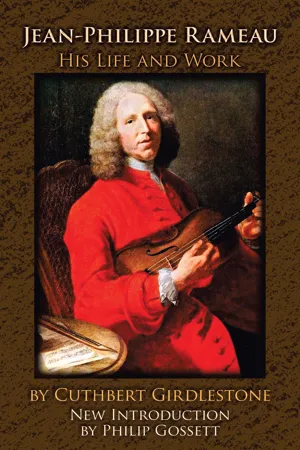

The definitive biography and critical study of Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), this volume deals at length not only with the composer's musical achievements but also with aspects of his life and work that made him one of the most important cultural figures in eighteenth-century France. Fascinating incidents include his central position in a musical controversy that excited the enmity of Rousseau, Diderot, and the Encyclopedists; his friendship and collaboration with Voltaire; and his position as the author of a treatise on harmony that endured for two centuries.

This critical evaluation focuses chiefly on Rameau's musical works, devoting entire chapters to his operas and ballets as well as his chamber music, cantatas and motets, and minor works. Additional topics include his links to Lully, his influence on Gluck, and the nature and importance of his acoustic and harmonic theories. Supplements include more than 300 musical examples, numerous useful appendices, indexes, an extensive bibliography, and a new Introduction by the distinguished musicologist and historian Philip Gossett.

This critical evaluation focuses chiefly on Rameau's musical works, devoting entire chapters to his operas and ballets as well as his chamber music, cantatas and motets, and minor works. Additional topics include his links to Lully, his influence on Gluck, and the nature and importance of his acoustic and harmonic theories. Supplements include more than 300 musical examples, numerous useful appendices, indexes, an extensive bibliography, and a new Introduction by the distinguished musicologist and historian Philip Gossett.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I. Life: The First Fifty Years

WHEN we study the lives of the older composers, we find again and again that they sprang from parents who were themselves musicians. Jean-Philippe Rameau is no exception to this apparent rule. At the time of his birth, his father, Jean Rameau, was organist at two churches in Dijon. This city, once the seat of the Dukes of Burgundy, had been since 1477 the capital of the Gouvernement of that province, the meeting-place of its Estates and its Parlement. In 1731 it was to become a bishopric. It boasted a college, founded in 1584 and belonging to the Jesuits.

For two generations Rameaus had been churchwardens of the parish of St. Médard, a post held by Jean’s father Antoine and his brother Andoche. Jean is said1 to have been introduced to the keyboard by a canon organist of the Sainte-Chapelle, the most venerable church in the city. Originally the ducal chapel, founded in the twelfth century and rebuilt in the fifteenth, it enjoyed the honour of being a peculiar and dependent only on the Pope. The Order of the Golden Fleece had its seat there; High Mass was sung in it every day, and it possessed a choir of precentors and boys. Stripped of the treasures with which the Valois dukes had enriched it, the Sainte-Chapelle survived the Revolution only to be pulled down in 1821 and replaced by a theatre.

At twenty-four, Jean Rameau became organist of the collegiate church of St. Étienne, the future cathedral.2 He held this post for twenty-seven years, combining it for a time with one at the abbey of St. Bénigne (the present cathedral), and leaving it in 1689 to occupy the organ-loft at Notre-Dame the next year. His alleged tenure of the organ at St. Michel is more than doubtful. For forty-two years he gave his services in one church or another of his native town. Rameaus were numerous in Dijon; we hear of them living in various districts, occupied with wool-shearing, clothing and employment in church or government administration. Jean seems to have been the first musician in the family.

He had married a wife from Gemeaux, a village some thirteen miles to the north-east. Her name was Claudine Demartinécourt; she was the daughter of a notary and belonged to the lesser nobility. Her family house, with its rounded angle, still stands at a street corner of the village, with a little eighteenth-century moulded wooden door. The name was spelt indifferently in one or two words. There exist two genealogical tables of her family—one of 1754, the other of 1630; it claimed to “go back to the Crusades”. Actually, the first Demartinécourt in history was a certain Claude who accompanied John the Fearless, then Count of Nevers, in the luckless expedition which went to help King Sigismund of Hungary against the Turks and was almost wiped out at Nicopolis in 1396. On his return he was made bailiff of Aumont by Philip the Bold, and in 1444 was knighted by Philip the Good. His son Antoine fought beside Charles the Rash at Morat in 1476.

Claudine bore her husband eleven children in twenty years. The first four were daughters, the fifth a son, the sixth another daughter. Jean-Philippe was the seventh. After him came four more sons, the last but one being Claude, the organist. Maret speaks of Demoiselle Catherine Rameau,

his daughter, who died in 1762, a good harpsichord player; for a long while she had taught music in Dijon but for several years before her death her infirmities had made her unable to work and her brother … made her an allowance which he always paid punctually.

Who was this Catherine? None of Jean’s daughters bears this name. If Maret’s information is correct—and there seems to be no reason to doubt it—Catherine may have been an unofficial name which had replaced her baptismal one in ordinary use.

Jean-Philippe was christened on September 25, 1683, at four o’clock in the afternoon, in the church of St. Étienne where the parishioners of St. Médard used an aisle while their own church was being rebuilt.3 His parents’ house still stands in the Rue Vaillant, Nos. 5 and 7; it was then called Cour St. Vincent, Rue St. Michel. He was two years older than Bach, Handel and Domenico Scarlatti, and one year older than Watteau, all of whom he was to outlive.

No infant-prodigy stories are laid to his account; the utmost claimed for him is that he knew his notes before he could read. It is his brother Claude, not he, who is alleged, like Daquin, to have given organ recitals when he was ten. For his schooling, Jean-Philippe was sent to the Jesuit Collège des Godrans, to-day the city library. A schoolfellow of his, the Carmelite Père Gauthier, told Dr. Maret that, though he was unusually quick, he spent his time in form singing or writing music. His performance in school was, in fact, so deplorable that the fathers asked Jean Rameau to take him away. Thus were dashed his parents’ hopes of seeing him enter the magistracy.

Maret says that, his many occupations and journeyings having prevented him from “chastening his language”, his use of French was not of the purest, and that a woman whom he loved having criticized him, he at once set about studying his tongue “par principes” and succeeded in a short while in speaking and writing it grammatically. Another version of this story, not told by Maret, is that he fell in love at seventeen with a young widow, who laughed at the spelling mistakes in his letters to her. But he was always a prolix and unclear writer, surprisingly so, in this eighteenth century when French prose reached its perfection and every letter writer handled his language with limpid elegance.

In later life he was not talkative and seldom spoke of himself. Chabanon, inditing his eulogy a few months after his death, says that the first half of his life is absolutely unknown, and that he never imparted any detail of it to his friends or even to his wife. When, in the year after his death, Dr. Maret, secretary to the Academy of Dijon, collected material for an Éloge, he had great difficulty in filling the gaps in the first forty years. Indeed, we know to-day more of Jean-Philippe’s existence between 1683 and 1723 than did any of his contemporaries.

By the age of eighteen he had made up his mind that he wanted to be a musician. His father sent him to Italy, the land which still enjoyed pre-eminence in music. He obeyed, but got no farther than Milan. To what he did there and what he heard we have no clue. A few months later he was back in France. In his old age he owned to Chabanon that he regretted not having stayed longer in the country “where he might have perfected his taste”. For the next twenty years his presence can be traced in various parts of France, but we cannot form a connected picture of his life. We do not even know whether he returned home on recrossing the Alps. He is said to have joined “as first fiddle” a troupe of travelling Milanese artists. At some stage he was in Montpellier, where a certain Lacroix taught him the “octave rule” for realizing figured bass.4 According to Maret, he never had a teacher of composition, though it seems unlikely that he did not receive some tuition from his father.

In January 1702, at nineteen, he was engaged as temporary organist at Avignon cathedral pending the arrival of the appointee, Gilles. His contemporary and future rival, Jean-Joseph Mouret, was still living in his native city, but we do not know whether the two met. In May of the same year he is found in Clermont, where he signs a six-year agreement to serve the cathedral chapter as organist.

All we know of this first stay in the capital of Auvergne is that the full term of the contract was not reached, since he was in Paris by 1706 at the latest, and that he must have left the town in good odour with the chapter since he was reappointed some years later. The earliest evidence of his presence in Paris is on the front page of his first book of harpsichord pieces, which gives his address and calls him organist to the Jesuit Fathers in the Rue St. Jacques and to the Fathers of Mercy, or Mercedarians; the latter’s church was in the Rue du Chaume.5

The only frequentation of which we can be reasonably sure is that of Louis Marchand, the most distinguished French organist of his day, who then held the post at the Cordeliers’, or Franciscans’, on the left bank. According to his obituary notice in the Mercure de France, he lived opposite the priory in order to hear the more easily the great man perform; “we know this from his own lips”. He derived much benefit from this intercourse, according to the writer, but Maret says that he was disappointed to find that Marchand was incorrect in the fugues which he played. He also says that the organist became jealous of his young visitor once he had seen some of Rameau’s organ compositions, and refused to have anything more to do with him. Of all these statements, I feel inclined to retain only the facts given by Rameau himself about his abode and interest in Marchand’s playing. The title-page of Marchand’s harpsichord pieces, dated 1703, calls him organist to the Jesuits of the Rue St. Jacques as well as to St. Benoît and the Cordeliers. I suspect that Rameau’s succession to the organ of the first of these churches was due to Marchand’s friendship.

In September 1706 he competed for the organ of La Madeleine en Cité and obtained it, but never took up the post, probably because he would have had to give up his two other organs. The issue for July 1708 of Ballard’s Airs sérieux et à boire includes his harpsichord pieces in a list of publications and calls him organist of the Jesuits and the Mercedarians, so that he may still have been in Paris at that time.

However, the next date in his life of which we can be sure is March 27, 1709, when he signs an agreement with the council of Notre-Dame at Dijon. He was succeeding his father, who had been there since 1690. As at Clermont, the agreement was for six years. The post was shared with one Lorin who was to play on ordinary occasions while Rameau’s services were required only on “vigils and holy days and at functions”. Once again he did not honour his agreement to the end, and four years later he was succeeded by the same Lorin. This inability to stay long in one place is a nomadic trait found also in his brother Claude and still more in Claude’s two sons.

By July 2, 1713, Jean-Philippe was no longer at Dijon. This time there is no hiatus in our knowledge of his movements, thanks to Léon Vallas, whose plotting of his stay in Lyons is the most important single contribution made to his biography since the eighteenth century. Before Vallas’s researches it was apparent, from an allusion in an article in the Mercure,6 that he had been in that city, but neither date nor length of stay was known.

In July 1713 the city of Lyons was preparing to celebrate the Peace of Utrecht. The festivities included music, and this was placed in the charge of one Rameau, “maître organiste”, who turns out to be our Jean-Philippe. Rameau’s plans were not carried out, for the city fathers decided to replace the concert by a distribution of alms, an expression of social sense which strikes us, perhaps unjustly, as exceptional at this period. In 1714 he is found employed by the Jacobins, or Dominicans, whose organ had just been restored; presumably he was organist there already in July of the previous year. Receipts signed by him exist; the last is dated December 13, 1714. This was a few days after his father had died, an event which caused a hasty visit to Dijon. He stayed on for his brother Claude’s wedding in January, and was back in Lyons before March 17, when he signed another receipt for a payment; now he is styled merely “maître de musique”, and he must have resigned from the Jacobins on his father’s death. His brother Claude had accompanied him to Lyons, and an agreement between them, settling their father’s affairs on their behalf and on that of their brothers and sisters, was signed there on March 24.

In April 1715 he is back in Clermont where he again signs a contract as cathedral organist, this time for twenty-nine years.7 His stipend of fifty livres a month is twice the amount of that stipulated by his earlier contract and his work includes teaching a chorister “or some other person” to play the organ, and keeping the instrument in order. The bishop at the time was Massillon.

These eight years in Clermont are the darkest in the mystery of his life between twenty and forty. It seems that his motets and cantatas were composed there or in Lyons and it was certainly in Auvergne that he carried on the studies which bore fruit in his first book, Traité de l’harmonie, published by Ballard in 1722, on the title-page of which he is described as “organiste de la cathédrale de Clermont”. According to a statement made many years later,8 he had pursued these studies from earliest youth. The following story proves that already in Lyons his mind was working on the fundamental bass.

In the pit of the Lyons opera house [a man] began to sing audibly and fairly loud the fundamental bass of an air whose words had struck him … I learnt that he was a workman whose occupation was hard and rough; his condition and work had long forbidden him opportunities of hearing music and he had been frequenting the opera only since fortune had smiled on him.9

Hitherto the records of the city and of the Puy de Dôme have revealed nothing about him, and we know no more about his stay there than what Maret tells us. There exist, however, some pupil’s harmony...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- Preface to the Dover Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Contents

- 1 Life: The First Fifty Years

- 2 Chamber Music

- 3 Cantatas and Motets

- 4 Lulli’s Tragédie en musique

- 5 Hippolyte et Aricie and Rameau’s Tragédie en musique

- 6 Castor et Pollux

- 7 Dardanus

- 8 The Later Tragédies en musique

- 9 Les Indes Galantes and Rameau’s Opéra-Ballet

- 10 d’Hébé and Rameau’s Pastoral Music

- 11 Platée and Comédie Lyrique

- 12 Minor Works

- 13 Life: The Last Thirty Years

- 14 Theories

- 15 Rameau and Gluck

- 16 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix A—Abodes and Churches

- Appendix B—Titles

- Appendix C—Prelude by Louis Marchand

- Appendix D—Excerpts from Hippolyte et Aricie, Dardanus and Les Boréades

- Index of Names

- Index of Subjects

- Index of Books and Articles by Rameau

- Index of Musical Works by Rameau

- Index of Operas, Masses and Oratorios by Composers other than Rameau

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jean-Philippe Rameau by Cuthbert Girdlestone, Philip Gossett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.