eBook - ePub

Available until 30 Sep |Learn more

WYSE Series in Social Anthropology

New Approaches to Understanding Morality

This is a test

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 30 Sep |Learn more

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access WYSE Series in Social Anthropology by Linda L. Layne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Taking the Measure of Selfishness and Selflessness in the Early Twenty-First-Century US and UK

Linda L. Layne

Introduction

Not quite as ubiquitous as ‘I’ and ‘my’, ‘us’ and ‘ours’, but certainly related to them, ‘selfishness’ is a profoundly familiar concept, against which readers were likely admonished as children. Although we may monitor our own behaviour and desires, selfishness always seems more easily recognizable in others. We are apt to find ourselves exclaiming, ‘How selfish!’ more often than we would like. We wish we did not have to encounter people who shout into their mobile phones on trains, bring an infant to a concert, arrive late for important events, or chat with a co-worker instead of serving us, but inevitably we do.

Such instances of selfish behaviour are much like ‘the wrongs’ encountered by the students of Jane Collier (1989) at Stanford in the 1970s: ‘My roommate used my toothbrush again’; ‘My mother said something embarrassing in front of my friends’; ‘Someone pushed ahead of me in line’ and so on. Such offences are relatively inconsequential, yet they often generate strong feelings, even moral outrage. ‘Can you believe it?’ or ‘How dare s/he?’ Collier was struck by how filled with emotion the ‘conflict narratives’ that she collected from her students were, in contrast to those she had collected in Chiapas, Mexico. The students reported feeling ‘angry, upset, frustrated, mad, hurt … at what they perceived as others’ wrongdoing’ (1989: 144), even though, in sharp contrast to the Mexican victim narrators, the Stanford students ‘did not posit deliberate malice on the part of those who harmed them’, nor did they think that the wrongdoer had singled them out. The students’ explanations tended to be that the other person had failed to follow the ‘Golden Rule’; they had not ‘put themselves in others’ shoes to think about how they would feel if they were the recipients of their own acts’ (1989: 146). Almost invariably, they understood these transgressions to be the result of ‘mere thoughtlessness’, which they used interchangeably with selfishness – ‘to be selfish is to think only of oneself, and so, by definition, not to think about others. To be thoughtless of others, is again, by definition, to think only of oneself’ (1989: 146).

Forty years on, is this still how ‘selfishness’ is understood and responded to in the US? Does it have the same meanings and attendant practices in the UK? To try to get a handle on how ‘selfishness’ is used today, and to do the same for what I initially assumed to be its opposite, ‘selflessness’, I turned to what, for anthropologists, may be unconventional sources. In so doing, I contribute to the emerging methodological tool kit for engaging in the ‘ethnography of moralities’ (Howell 1997), or as Lambek (2010) might put it, ‘ordinary ethics’. My sources include dictionaries, Wikipedia, newspaper articles, blogs and popular books. They are likely to be among the sources ‘my natives’ – twenty-first-century, literate, English-speaking residents of the US and UK – would consult if they were interested in, troubled by, and/or aspiring to embody these moral qualities.

Starting in 2014, I was electronically alerted each time The New York Times (NYT), the newspaper of record in the US, published an article that mentioned ‘selfish’ or ‘selfless’. For the UK, I drew mostly on theguardian.com. Although not as popular as the UK’s best-selling Daily Mail, its readership is more similar to that of the NYT. (Both papers have US and UK editions and are available online to readers in the other country.) Articles addressing selfishness outnumbered those on selflessness, usually with a ratio of at least 2:1, and on one occasion 9:1.

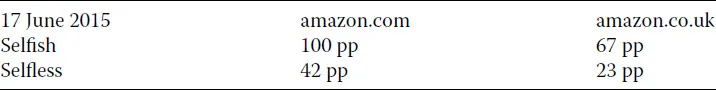

In June 2015, I searched for the terms ‘selfish’, ‘selfishness’, ‘selfless’ and ‘selflessness’ on amazon.com, Amazon’s US site, and amazon.co.uk, its British site and the company’s third-largest market. I searched under the category ‘books’ but once inadvertently searched under ‘all’, thereby stumbling upon a trove of consumer goods touting these moral qualities. Together with the books, these items provide a disturbing picture of what Fassin describes as ‘the banalization of moral discourse and moral sentiments in the public sphere’ (2014: 433). The US site produced significantly more results than the UK site, reflecting the larger market size, and on both sites, ‘selfish’ produced significantly more results than did ‘selfless’.

Thanks to online shopping sites like Amazon, digital newspapers, music and video streaming, Britons and Americans have easy access to many of the same sources. Thus, it should be no surprise how much overlap there is in the ways selfishness and selflessness are used in the public sphere. Some of the continuities in use can be traced to the moral struggles in Britain and its American colonies during the eighteenth century in the wake of the consumer revolution taking place on both shores (Barker-Benfield, this volume, 1992, 2010, 2018). Differences in contemporary usage are noticeable too, such as the prominence of Christian sources in the US and the more frequent application of these moral judgements to ‘society’ in the UK. Other anthropological methods or foci would likely reveal greater differences between the two countries.

Table 1.1. Result of Amazon search for the terms ‘selfish’ and ‘selfless’.

Table 1.2. Synonyms for ‘selfish’ and ‘selfless’.

Selfish | Selfless |

egocentric egotistic egotistical egomaniacal self-centred self-absorbed self-obsessed self-seeking self-serving wrapped up in oneself inconsiderate thoughtless unthinking uncaring uncharitable mean miserly grasping greedy mercenary acquisitive opportunistic | unselfish altruistic self-sacrificing self-denying considerate compassionate kind noble generous magnanimous ungrudging charitable benevolent openhanded |

I found the terms were being applied to a remarkably wide range of objects and subjects: societies, religions, eras, politicians, financiers, husbands, bosses, mothers, children, single people, firefighters, soldiers, athletes, missionaries and humanitarian aid workers. Moral judgements get mobilized on a personal level – ‘my selfish husband’, ‘my boss, the narcissist’ – but also at the level of social categories: ‘Generation X’ers are too self-absorbed’. The modes and occasions for judging oneself or others according to these moral criteria include opinion pieces, advice manuals, children’s literature, bodice rippers, spiritual guides, music, movies, phone cases, coffee mugs and bibs. The tone registers (Lambek 2015: 11; Rapport 1997: 74) range from earnest and preachy to seductive and ironic.

Moral evaluations of selfishness and selflessness are fluid and wide-ranging. Neither concept is persistently ‘good’ or ‘bad’ and accusations of selfishness are sometimes embraced, the epithet co-opted as a sign of power and defiance. This ‘rich semantic ambiguity’ (Strathern 1980: 179) is contingent on context – who is doing the evaluating, what or who is being evaluated, and with whom the evaluation will be shared.

Selfish and Selfless: Core Symbolic Categories in Contemporary US and UK Cultures

Clearly ‘selfishness’ and ‘selflessness’ are multivalent and polysemic, and at least in some instances they work as part of what Needham (1973) would call a ‘dual symbolic classification’ system. Addressing as they do the ‘proper’ and ‘improper’ relationship between self and others, these classifications are as basic as ‘nature’ and ‘culture’. Yet, whereas nature and culture have received significant and sustained anthropological and historical analysis,1 the same cannot be said for selfishness and selflessness. How is this possible? How could we have missed this?

For my inquiry into these incredibly slippery concepts, I found structuralist approaches helpful. The anthropological debate concerning the relationship between nature/culture and female/male (MacCormack 1980; Ortner 1972; Strathern 1980), that started with, then challenged, Levi-Strauss’s structuralism, provides a particularly useful model for how to make sense of the many and varied ways in which selfishness and selflessness are deployed and their gendered associations. There are striking similarities in the types of relationships Strathern (1980) observed between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ in the twentieth-century UK, and what I have found for ‘selfishness’ and ‘selflessness’, and not merely because of the extent to which they are attributed to ‘human nature’.

My survey of contemporary usage in American and British public spheres indicates that, as with nature/culture, selfish/selfless are understood alternatively, and even simultaneously, to operate as a dichotomy, be in a hierarchical relationship to one another, occur on a continuum, and/or have the ability to transform one another (Strathern 1980: 182). In the first part of the chapter, which I call ‘Selfish Is to Selfless as Nature Is to Culture’, I do not suggest any simple analogy, but rather use this trope to highlight the complexity and dynamism of these categories in use. I provide ethnographic detail about where, by whom, and how successfully these different types of relationships are marshalled in contemporary usage.

I discuss the frequent use of dichotomies and multiple sources of tension that undermine them. Rather than thinking of hierarchical relations as distinct from dichotomous ones, I show how the two are linked in popular usage, drawing on insults, spiritual guides, cartoons and children’s books. Next, I address continua and transformations and show how, here again, two types of relationships are linked in practice. Moral transformations, whether it be of individuals or societies, are routinely conceptualized in terms of placement on a continuum. The rhetoric of health and illness informs much current thinking about the ‘right amount’ of these moral inclinations. In the US, the $9.9 billion self-help book industry (Groskop 2013; Kachka 2013; LaRos 2018) includes numerous titles aimed at the transformation of selves and others – to become a more caring, generous, selfless person or help others to do so, and barring that, to become better able to cope with selfish people. Self-help books are also growing in popularity in the UK (Rigby 2013), where ‘“intellectually credible” self-improvement books [were expected] to outsell celebrity biographies in 2014’ (Groskop 2013). Most of the books that address the moral transformation of society from community-minded to selfishly preoccupied – that is, moving in the ‘wrong’ direction along the continuum – are British.

I suggest that these types of relationships (dichotomy, hierarchy, continuum and transformation) can be understood as folk theories about the moral universe. Cognitive anthropologist Willett Kempton used the notion of ‘folk theories’ to describe the mental models that upper-middle-class residents of Princeton, NJ had about how their home thermostats worked. By ‘folk’, he signified that the theories were shared and that they were acquired ‘from everyday experience or social interaction’, and by ‘theory’, he highlighted the use ‘of abstractions, which apply to many analogous situations, enable predictions, and guide behavior’ (Kempton 1986: 75).

In the second part of the chapter, I build on my analysis of four types of relationships and the relationships between them by turning my focus to values/categories relationships as modelled by Sahlins (1985) and Robbins (2004). Their attention to ‘the relationships between values and values, categories and categories, and values and categories’ (Robbins 2004: 6) is a helpful guide for thinking about variations and sets of combinations of the ways these categories are being used, and the values assigned them in the US and UK in the early decades of the twenty-first century. I present six variations in the meanings of the categories selfish, selfless and unselfish and/or the values attributed to them: selfishness is good if it protects private property, or because it is natural, or because it is really selflessness in disguise; selfishness is bad, but bad is good (and sexy); selflessness is bad because it is really selfishness in disguise, and the alternative – it is good, because it is really selfishness.

Part I. Selfish Is to Selfless as Nature Is to Culture: Dichotomies and Hierarchies, Continua and Transformations

Dichotomy/ies

Dichotomies have been rejected by post-structuralist scholars because they present an overly simplistic and static representation of complex and dynamic cultural symbols and practices (Kopnina 2016; Nygren 1999). If one is to understand how selfishness and selflessness are actually used, however, one cannot ignore their frequent use as a dichotomy, that is, as two halves o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations, Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction. Self, Selfish, Selfless

- 1. Taking the Measure of ‘Selfishness’ and ‘Selflessness’ in the Early Twenty-First-Century US and UK

- 2. ‘Sentiment Has Struggled with Selfishness’: Selfishness, Sensibility and Gender in the Late Eighteenth-Century British Antislavery Campaign

- 3. Selfless Advocacy? Profeminist Men’s Movements in Late Twentieth-Century Britain

- 4. ‘Doing the Right Thing for My Child’: Self Work and Selflessness in Accounts of British ‘Full-Term’ Breastfeeding Mothers

- 5. Sexism, Separatism and the Rhetoric of Selfishness: Single Mothers by Choice in the US and UK

- 6. Selfish Masturbators? The Experience of Danish Sperm Donors and Alternatives to the Selfish/Selfless Divide

- 7. Inroads into Altruism

- 8. On Being Selfish – Or Not: Explorations of an Idea from the Mountains of Oaxaca and the Alaskan Tundra

- Conclusion. Starting Points: Modest Contributions to the History and Anthropology of Moralities and Ethics

- Index