- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Light for the Artist

About this book

Intermediate and advanced art students receive a broad vocabulary of effects with this in-depth study of light. The guide offers detailed descriptions that start with the basics — the direction of light, reflections, and shadows — and advance to studies of light in natural and manipulated situations. Examinations of subtler light effects include foreshortening, field effects, multiple light sources, colored light, depicting the light source, and the behavior of light on shiny surfaces.

Lavishly illustrated with diagrams and paintings, this volume applies its principles to figure, still life, and landscape paintings. Author Ted Seth Jacobs stresses the importance of comparing real-life vision to the canvas, since no system of rules can substitute for close and careful observation. Jacobs points out common errors, suggest light effects that artists should keep in mind, and discusses how preconceptions can be put aside in order to see the world more clearly.

Lavishly illustrated with diagrams and paintings, this volume applies its principles to figure, still life, and landscape paintings. Author Ted Seth Jacobs stresses the importance of comparing real-life vision to the canvas, since no system of rules can substitute for close and careful observation. Jacobs points out common errors, suggest light effects that artists should keep in mind, and discusses how preconceptions can be put aside in order to see the world more clearly.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE NATURE OF LIGHT: Its Structure, Action, and Effects

THE VISIT OF THE BEY, oil on canvas, 20″ × 24″ (50.8 × 61.0cm), 1988 (work in progress)

WRITING a rather analytical study of light is somewhat intimidating. Viewed from our human scale of observation, light seems at once cosmic and nearly immaterial. How can we hope—in fact, why should we wish—to pin down such an elusive element? How can we quantify this paradoxical living entity, ever-changing and ever-present? And what could be more exquisitely subtle in its appearance?

Within these limitations, I find it is still possible to say something useful to the artist on the basis of what we can observe about light by using nothing more or less sophisticated than the human eye. We all have in common this faculty of sight. If we pay attention to what it is constantly showing us, we can learn a great deal.

THE DIRECTIONAL QUALITY OF LIGHT

Perhaps the first observation that we can make about light—and one that will remain of paramount importance—is that it comes from somewhere. Visible light has a source. Natural or mechanical, from a sunny or cloudy sky, from lamps, candles, fire, or firefly, it radiates outward from a point of origin, from some energetic source.

If light is radiating from a source, it is going somewhere. That is to say, it has a directional orientation. For us earthlings, the immediate source is Aton, our sun (I say “immediate” because I don’t think there is as yet any conclusive knowledge about where the sun and all else ultimately came from).

This light originating with our sun can be channeled and presented to us through secondary sources such as windows, lamps, or cloud cover. The light effect that we painters are called upon to suggest in any given situation comes from a given source. Whatever subject we see before us is lit from a certain direction. In cases where there is more than a single light source, each source has its own directional aspect. It is necessary for artists to know where the light is coming from whenever we look at a model or imagine a subject. Otherwise, our symbolic ideas will insinuate themselves between our awareness and our process of vision, and we will fail to notice the effects of the light. This is often as much the case for advanced artists as it is for beginners. We must be very alert!

Determining the Direction of Light. How exactly can the direction of the light be established? Although at first glance this question may seem unnecessary, it is in fact not always easy to determine the exact angle of the light arriving on the model. One simple and sure method is to look for the cast shadows. Every opaque object blocks the passage of light and casts its shadow after itself. These shadows are, so to speak, thrown “behind” the object, in the same direction as the incoming light. Their exact shape is conditioned by the shape of the object upon which they fall, but overall they lie along the line of the arriving light ray, like an arrow reaching its target.

For example, if the light is from the right, the cast shadow will be thrown toward the left; if the light arrives from below, shadows will be cast upward. Even cast shadows that are diffuse and blurred will still be thrown in the direction of the arriving light. An experiment can be made that clearly shows this directional principle. If you place an object on a tabletop in lamplight, you can find the point on the edge of the cast shadow that corresponds to that point on the subject. If you connect these points with a thread and pull it taut, you can then extend the thread in a straight line that will pass through the center of the light bulb.

By habitually noticing where the cast shadow falls in relation to the model, we can establish the position of the source of light. This can be useful, for example, painting indoors when we know the light is arriving through a window but cannot otherwise determine its exact angle of incidence.

From Source to Subject. Following from the idea that light comes from the direction of its source is the conclusion that it is then propagated through space. It has a trajectory. Given the scope and dimensions of our usual models, it is not necessary for artists to question whether light is bent as it moves through the cosmos. For our purposes, we may treat light as moving in widening rays in a straight path from source to model.

REFLECTION: LIGHT BOUNCING OFF A SURFACE

This idea that light moves in straight beams from its source leads us to two vitally important conclusions. The first is that light, like almost anything thrown or propagated, bounces off a hard surface. The part of light that our eyes register has apparently bounced off an object. The direction of its reflection follows the law of incidence and reflection, which states that light bounces from a surface at the same angle as that of its arrival, but in the opposite direction. It moves much as does a ball thrown against a wall. If we throw a ball from a wide angle, it will bounce off the wall at that wide angle in the opposite direction. If we throw the ball directly in front of us, it will bounce back to us. It is necessary to understand and remember this principle. Besides its general applications, it is responsible for some rather special effects in the case of highlights and light reflected into the shadow.

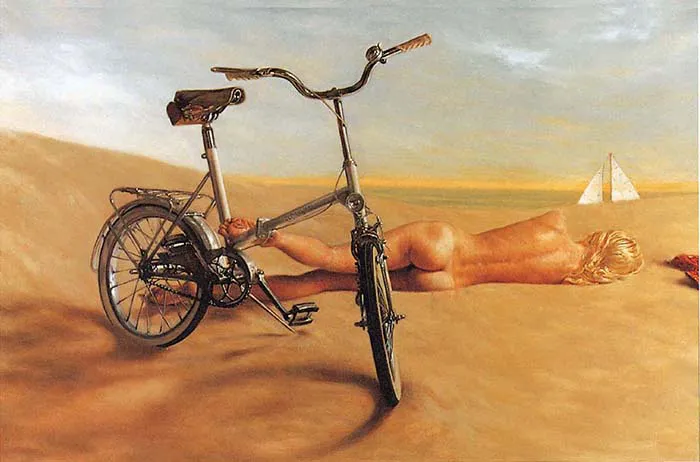

WOMAN WITH A BICYCLE, oil on canvas, 20″ × 30″ (50.8 × 76.2 cm), 1972

The cast shadows on the ground indicate where the light source is located. For example, connect the hub of the front wheel with its cast shadow on the ground to find the angle of the light source.

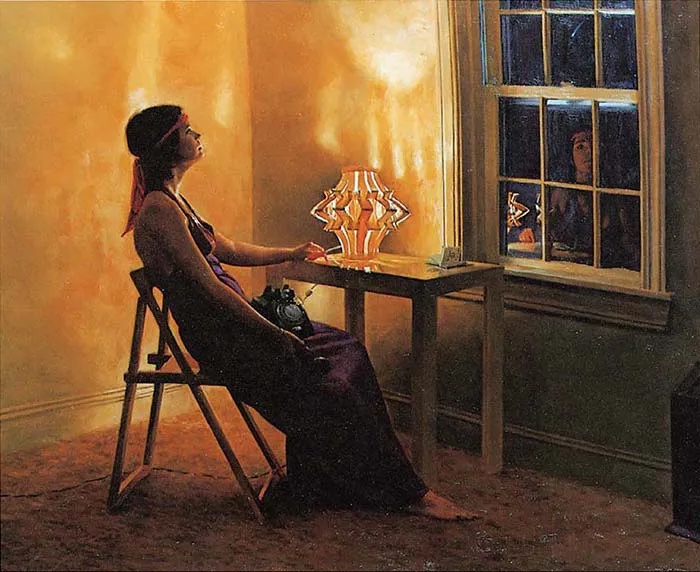

THE COMET KOHOUTEK, oil on canvas, 18″ × 24″ (45.7 × 61.0 cm), 1974

In this composition, I wished to use the curiously shaped lamp and the light it radiates as a metaphor for the comet that is visible through the window. Despite the literary content of the scene, the painting itself is essentially a study of light effects. In the same manner, the nineteenth-century Italian genre painter Chierici used highly anecdotal subject matter as a vehicle for brilliant paintings of the effects of light on form.

MOUNTED OWL, oil on canvas, 12″ × 15″ (30.5 × 38.1 cm), 1987

In this subject, the light arrives from the lower left and throws cast shadows upward, toward the upper right. These can be seen on both the owl and the wall. It is instructive to make pictures with the light coming from directions other than those you usually see.

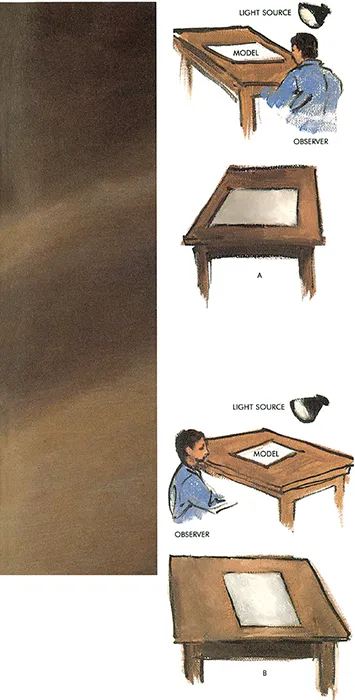

This is a schematization of how the same model will appear from two differet positions of the observer.

The Reflective Shift. The effects of light—the distributions and gradations that we see on the model—do not look the same from different points of view. These effects depend upon the positions, relative to one another, of model, observer, and light source. Because these relative positions produce different angles of incidence and reflection to our eyes, it is very important to understand the law of incidence and reflection. Because of the effects of that law, the gradations of light, known as “values,” are not distributed in a uniform progression—a smooth, descending curve of intensity. The reflective action of light can cause what will appear to us as an uneven gradation. The value changes can be displaced, or “shifted,” because of reflective effects.

For example, if we keep the light and model in the same place, but change our own position as observer, moving to face the light source, the lighter values on the model will shift toward us, even though the light source has not moved. The gradation of value will seem reduced, or “flattened.” This “reflective shift” is, of course, always happening everywhere, but in some situations it becomes, if you will pardon the expression, “glaringly” apparent.

Imagine a sheet of paper lying on a tabletop, under a lamp fixed in place. The illustration shows how the paper will appear to us if we move from position A to position B. As we move to B, the brighter values are displaced toward us by the angle of reflection. The gradation of value from position B appears flatter, less varied from light to dark.

What we see are relationships caused by positional factors.

SHADOW: THE ABSENCE OF LIGHT

The second vitally important conclusion that derives from the action of light moving as a beam from a source is that it can only illuminate what lies in its path. Only part of any three-dimensional object will face the light. Whatever parts do not receive light will fall into what is called “shadow.” Shadow, then, is the opposite of light, its absence. If we wish to suggest what is seen, this division of everything into light and shadow is one of art’s most important principles.

In nature we find both dark lights and light shadows, but for convincing results the artist ought always to distinguish which is being represented. The suggestion of something seen will be considerably weakened if the artist is confused about what is in light and what is in shadow.

A Word About Half-tones. If we consider that light travels in beams, it is impossible to conceive logically of a plane that is not facing either toward or away from those rays. Although some parts of an object face more and some with “cast shadows” that less directly into the light, I cannot light. These are called conceive of an object that is turned neither away from nor toward the source. I cannot imagine a mysterious angle or plane that lies somehow between light and shadow. Probably what is meant by “half-tones” is what I call the darker lights, that is, those surfaces still receiving some light but not turned very directly into its path. The semantic distinction is important because the concept behind the idea of a half-tone tends to produce excessively soft and indecisive work.

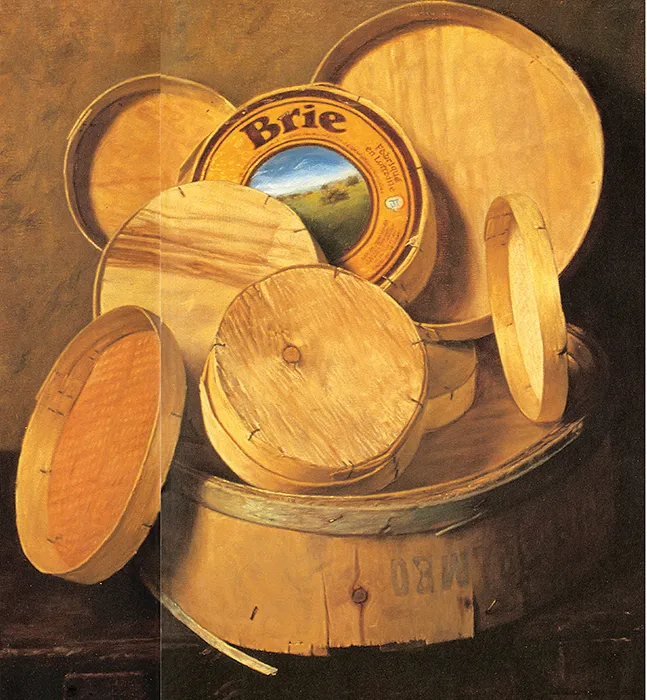

BRIE, oil on canvas, 22″ × 20″ (55.9 × 50.8cm), 1981

Shadows occur where the curves of the boxes turn away from the beams of light. These are called “form shadows” and should not be confused are projected by one form onto another.

LIGHT MOVING THROUGH SPACE

The fact that light emanates from a source produces another extremely important effect. As light leaves its source and travels in widening beams through space, it decreases in intensity. It pales on its journey. Of two stars of the same innate brightness, the nearer will appear more brilliant. Light entering a room through a window drops off quite noticeably in strength as it travels through space. The same is true for light radiating from a lamp or fixture. This effect can clearly be seen on a blank wall, where the section nearer the source of light will be brighter than the farther areas. We can see a fairly even progression of intensity across a wall lit by a single source. It is vitally important for the artist to represent this gradual diminution in intensity. Because of our attachment to symbolic preconceptions, it is quite easy not to notice it. This is a very common fault among students and even sometimes with the more experienced.

The light source in both these paintings is at the upper left. In this incorrect version, the chair on the right is placed much farther from the light than the chair on the left but has been painted in inappropriately high values. It is therefore in harmony with neither the space around it (which has been properly darkened) nor its position relative to the light source. This dissonance gives the picture the feel of the expressionistic style, which is characterized by raw emotional power produced by exaggerations and distortions.

Here, the values of the right-hand chai...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Symbolism and Perception: Word Versus Light

- The Nature of Light: Its Structure, Action, and Effects

- Toward A Philosophy of Perception

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Light for the Artist by Ted Seth Jacobs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art Techniques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.