![]()

CHAPTER ONE

From Independence to 1989

IN NOVEMBER 1989, the world’s attention was riveted on global transformations. That autumn, the one-party states of central and eastern Europe and the Balkans crumbled like dominoes. In November, the most dramatic development of all occurred. The Berlin Wall, which had stood for three decades as a symbol of the world’s division between East and West, came down, signaling the imminent end of the post-1945 world order and the dawn of a new era in global history and international relations.

In India, the nation’s attention was riveted on events within the country. In November 1989 India went to the polls for the ninth time since independence in 1947 to elect the national government. The (normally) five-yearly election to constitute the directly elected chamber of the national Parliament, the Lok Sabha, “House of the People,” is the centerpiece of India’s democratic process and the world’s biggest exercise of democratic franchise.

The November 1989 election was a particularly tense and fraught affair. The ruling Congress party, founded in 1885 as the Indian National Congress, which led the mass struggle for freedom from colonial subjugation under Mohandas K. Gandhi’s guidance from the early 1920s onward and had thoroughly dominated independent India’s politics for over four decades, faced a spirited challenge from a rainbow spectrum of opposition parties. This spectrum included groups comprised of old and new defectors from Congress, “regional” parties based among ethnolinguistic communities in some of the Indian Union’s (then) 25 states, communists, and right-wing Hindu nationalists. The communists and Hindu nationalists had formed a loose alliance with the “National Front”—an umbrella grouping of anti-Congress political formations based primarily in northern India and regional parties based primarily in the south of the country. The Congress leader and prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi, who had inherited both mantles five years earlier, aged just 40, through hereditary succession from his mother, Indira Gandhi (prime minister 1966–1977 and 1980–1984) and grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru (prime minister 1947–1964), faced a tough personal challenge from the National Front’s leader, Vishwanath Pratap (V. P.) Singh, who had until 1987 been a close colleague. V. P. Singh had served during Indira Gandhi’s second premiership as the chief minister (head of the elected government) of Uttar Pradesh (UP), India’s most populous state and a vast sprawl across the Gangetic plain of northern India, from 1980 to 1982. He had then served in Rajiv Gandhi’s cabinet as finance minister, and briefly as defense minister, between 1985 and 1987. Since his dismissal from the cabinet and resignation from Congress in mid-1987, V. P. Singh had emerged as the focal point for the rainbow spectrum of parties striving to undermine Congress’s entrenched dominance of India’s polity. The opposition claimed that Singh had been hounded out of the finance and defense ministries for seeking to investigate high-level corruption in the Congress party and Rajiv Gandhi’s government.

The November 1989 election was the turning point in India’s evolution as a democratic country. In the eighth Lok Sabha, elected in December 1984, Congress had held 415 of the 542 seats, or about 77 percent of the parliamentary “constituencies”—single-member electoral districts spread across the country where the candidate who wins the single largest share of the vote becomes the constituency’s representative in Parliament through the plurality or “first-past-the-post” electoral principle. Five years later, the party’s tally plummeted to just 197 of the 543 seats, about 36 percent of the total. The Congress share of the nationwide popular vote slumped from 48.1 percent in 1984 to 39.5 percent in 1989. While at first glance less than drastic, this fall of nearly nine percentage points in fact represented a severe erosion, a loss of nearly one-fifth of the party’s vote base. This decline in popular support combined with a second factor—the coordinated though not totally unified challenge from the diverse spectrum of opposition parties, who tried to put up a common candidate against Congress in as many parliamentary constituencies as possible—to deal the grand old party of India a devastating political defeat.

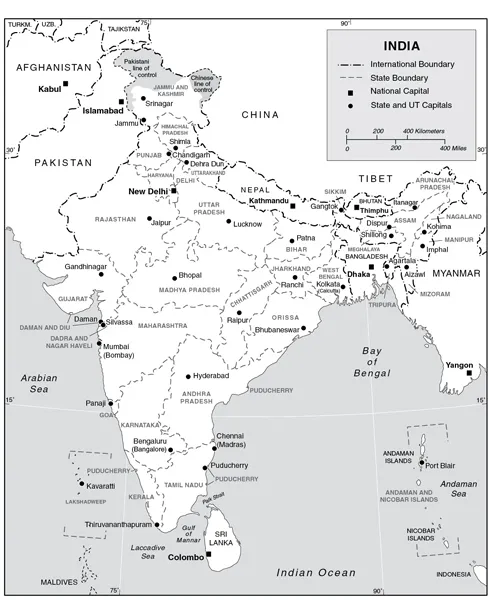

The overall outcome was a “hung parliament”—a fractured verdict in which no party or preelection coalition wins an absolute majority (at least 50 percent plus one) of seats in the legislature—in which Congress was still the single largest party. The Janata Dal (People’s Party), a federated entity of anti-Congress factions based primarily in northern India and fronted by V. P. Singh, won the second largest number of seats—142. The bulk of the Janata Dal’s seats in Parliament came from two giant states in predominantly Hindi-speaking northern India, UP and Bihar, where the party won 54 of 85 and 31 of 54 seats, respectively. In UP, V. P. Singh’s home state, the Congress seat tally collapsed from 83 of the 85 constituencies won in 1984 to just 15 in 1989, and in Bihar from 48 to just 4. The other big gainer was the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (Indian People’s Party; BJP), India’s established but hitherto marginal right-wing party, which increased its parliamentary representation from 2 to 86 seats, almost all of which were won in a swathe of states in northern and western India. On the other side of the political spectrum, a left-wing coalition led by India’s largest parliamentary communist party, the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPM), won in 53 constituencies, 38 of which were in the populous state of West Bengal in eastern India. Congress was routed in almost all the states of northern, eastern, and western India.1 As many as 135 of its 197 seats in Parliament came from just five states: the populous western state of Maharashtra (of which Mumbai, previously Bombay, is the capital), and the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu in southern India. (And in Tamil Nadu, in India’s deep south, Congress’s success was due to its electoral alliance with one of the state’s two main “regional” parties.)

Together, the Janata Dal, the BJP, and the communist-led bloc had a majority of seats in Parliament. In early December V. P. Singh assumed the prime ministership of India at the head of a Janata Dal/National Front minority government, propped up from its two flanks by “outside support” extended by the Hindu nationalists and the communists. His tenure as premier was to be short-lived—just 11 months, until November 1990—but that brief period was extraordinarily eventful and fraught with vast implications for India’s political trajectory through the 1990s and beyond.

Congress had recovered from serious electoral setbacks on two previous occasions—in the fourth national election held in 1967 and the sixth national election in 1977—and re-asserted its hegemony in India’s polity within a few years by winning decisive victories in the fifth national election (1971) and the seventh national election (1980). But the crisis of hegemony revealed by the debacle of late 1989 was to prove permanent. In midterm national elections held in mid-1991, the party won 232 of the 543 parliamentary constituencies—well short of an absolute majority in Parliament (272 seats) but an improvement on the 197 seats the party had managed to win a year and half earlier. This semblance of recovery was an illusion, however, and primarily due to a lesser degree of unity among the range of anti-Congress parties compared to 1989. In fact, the party’s share of the nationwide vote declined further in 1991—from 39.5 percent to 36.5 percent. In UP, Congress won just five of the 85 parliamentary constituencies; in Bihar, just one of the 54 constituencies. Congress had virtually ceased to exist in the two northern states that together accounted for more than a fourth of India’s Parliament.2

The ninth national election of November 1989 was the watershed in the evolution of the world’s largest and most complex democracy, as the Congress era (1947–1989) yielded to the post-Congress era. Since 1996 India has been governed by unwieldy and polyglot coalition governments, in sharp contrast to the single-party Congress governments of the first four decades after independence. And in the two decades that have elapsed since the passing of Congress hegemony from India’s politics, the “regionalization” of India’s political landscape has deepened and intensified, as parties with a popular base in just one of the 28 states comprising the Indian Union—and particularly in the dozen or so most populous states—have proliferated and utterly changed the terms and parameters of the functioning of the world’s most populous, most unruly, and most vibrant democracy.

Formation: The 1950s and 1960s

The paradox of the long Congress era in independent India’s political history is that the party was never as dominant at the societal level, among the masses of India’s people, as it was at the institutional level, where it wielded formidable levers of power and patronage. Throughout its four decades as the hegemon and pivot of Indian politics, the Congress party never succeeded in gaining an absolute majority of the national vote. It came closest to the 50 percent threshold in the eighth national election of December 1984 when, after the assassination of Indira Gandhi, party leader and prime minister, the party, led by her neophyte son Rajiv, polled 48.1 percent of the nationwide ballots riding an all-India “sympathy wave.” In independent India’s first national election, held between October 1951 and February 1952, Congress secured just 45 percent of the nationwide vote. In subsequent elections in 1957, 1962, 1967, 1971, 1977, and 1980, the party obtained 47.8 percent, 44.7 percent, 40.8 percent, 43.7 percent, 34.5 percent, and 42.7 percent, respectively. This record stands in contrast to that of a true “majority” party, South Africa’s African National Congress. In the first postapartheid national election of 1994, the African National Congress won 63 percent of the nationwide vote and improved to 66 percent in 1999 and 70 percent in 2004, before declining slightly to 66 percent in 2009.

Congress’s hegemonic power in India’s polity was enabled and sustained by the “first past the post” electoral system operating across single-member parliamentary constituencies—the same system as that of India’s former colonial ruler and fellow parliamentary democracy, Britain. The system rewards the party that wins the single largest share of the popular vote with a disproportionately high share of seats in the legislature. This system typically magnifies the plurality share of the popular vote secured by the frontrunner into a decisive and often commanding parliamentary majority. Thus in Indian democracy’s founding election in 1951–1952, 55 percent of Indians who voted cast their ballots for non-Congress parties, but Congress won 364 of the 489 seats in the first national Parliament. In an election held under rules of proportional representation, based on party lists, the party would have been entitled to 220 of the 489 seats. The pattern recurred in all national elections until the watershed of 1989, with the exception of 1977, when the ruling party was resoundingly defeated by a hastily cobbled together opposition coalition in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s overt attack on the nation’s democratic edifice during her dictatorial “Emergency” regime of 1975–1976. In 1957 Congress got 371 of the 494 seats in the Lok Sabha, and in 1962 it bagged 361 of the 494. In 1967, when the party suffered—and survived—the first major jolt to its supremacy, it still won a reduced majority of 283 of the 520 seats in Parliament. In 1971 Congress rebounded with 342 of the 518 seats in Parliament. In 1980, as the victorious opposition coalition of 1977 disintegrated amid factional and personality feuds, necessitating a midterm election, the grand old party returned to power under Indira Gandhi’s leadership, winning 353 of the 529 parliamentary constituencies. In 1984 her older son and successor, Rajiv Gandhi, won a victory whose scale surpassed those of his grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru, prime minister from independence in August 1947 until his death in May 1964, and his mother. In the mid-1980s, with Congress holding 415 of the 542 seats in Parliament’s directly elected chamber, it did not seem that the end of the Congress era—and of dynastic rule—was at hand.

The four decades of Congress hegemony were not solely due to the electoral system. A second, powerful factor was at work—the fact that no other party existed, or arose, that could remotely rival the India-wide voter base and organizational presence that was Congress’s inheritance from its leading role in the mass movement for freedom from colonialism between the early 1920s and 1947. Thus the majority non-Congress vote was splintered from the first election of 1951–1952 onward among a diverse spectrum of opposition parties and groupings, and Congress towered over its disparate assortment of Lilliputian rivals. This meant that Congress’s dominance of India would not be undermined until the party’s base was severely weakened in at least a critical mass of the dozen or so most populous states of the Indian Union. That would not happen until the late 1980s, when it would signal a great transformation in the nature of India’s politics, a transformation that would unfold through the 1990s and continues to unfold in the early twenty-first century.

The fact of one-party dominance was a very mixed blessing for India. In a vast country inhabited by numerous ethnic and linguistic groups, religious communities and castes—a mosaic of diversity—it was obviously useful for the newly independent state and its nascent polity that a nationwide party with strong popular legitimacy existed to take on the many challenges of postcolonial state-building. The existence of the Congress party was in this sense a boon during the early years of independent India. As an Indian author has observed, “in the fifties and sixties [Western] reporting about India was full of metaphors of the region-of-uncertainty or area-of-darkness kind. There was a great deal of superior moaning about how awful, poor, divisive, filthy … India was.… Of course democracy simply did not have a chance in this illiterate and hungry land; at best it would be a farce and at worst a chaotic Babel that would encourage all the latent fissiparous forces, ensuring the … destruction of the country.”3

That this gloom-and-doom prognosis proved incorrect is due in large part to the Congress party providing the glue that held a vast and diverse nation together. The contrast with the early years of Pakistan, the other state to emerge in the subcontinent in 1947, is instructive. There the Muslim League, the party that spearheaded the movement for Pakistan, proved to be weakly rooted in the regions of northwestern and eastern India that became Pakistan, and having achieved its objective of a sovereign Muslim state, the party lost its raison d’être and withered away within a few years of the formation of Pakistan. No other party or parties with a Pakistan-wide presence and purpose arose to fill the vacuum. The void provided the opportunity for an alliance of civilian bureaucrats and military officers based in West Pakistan (the post-1971 rump Pakistan) to increasingly dominate the country during the 1950s, with disastrous consequences for both democratic development and relations between the two wings of Pakistan (East Pakistan seceded in 1971 and became sovereign Bangladesh). Pakistan’s first military coup in 1958 set the country firmly on the path of military-bureaucratic authoritarianism, which continues to shape the fate of the erstwhile West Pakistan more than a half century later. Thus “the Muslim League failed to fulfill the nation-welding role which, under different circumstances, the Chinese Communist Party provided from just this time onward in China, the Indian National Congress in India, and later the United Malay National Organization in Malaysia and the Tanganyika African National Union in Tanzania.”4

India’s constituent assembly finished its work by late 1949, and the Republic of India was proclaimed on January 26, 1950. During Nehru’s long tenure in office, the country completed three national parliamentary elections within 15 years of independence, setting India firmly on the path of democratic development (by contrast, the constitution of Pakistan was not framed until 1956, and its first nationwide election was held in 1970, 23 years after the country came into existence). By the mid-1950s the crucial question of the political structure of the Indian state had been resolved, and the process of organizing India as a union of relatively autonomous ethnolinguistic states—the broad principle being that significant language groups should have their own states—was set in motion. (This process proceeded incrementally, and the drawing of the internal political map of India took until the early 1970s, although it was substantially complete by 1966. Prior to this, between 1947 and 1949 several hundred nominally independent feudal principalities known as “princely states” scattered across the country, a residue of the British practice of “indirect rule,” were absorbed into India, in all but a few high-profile cases without conflict.) Also in the mid-1950s, an important “modernization” was enacted by Parliament with the reform of Hindu family law on inheritance, marriage, divorce, and adoption.

But if the Congress party of Nehru’s India was a guarantor of stability and democratic development, it was also a force of profound social and political conservatism. The Nehru regime “was based on a coalition of urban and rural interests united behind an urban-oriented industrial strategy. Its senior partners were India’s small but politically powerful administrative, managerial and professional urban middle classes and private-sector industrialists.… The junior partners were rural notables, mostly large landowners who survived intermediary abolition and blocked the implementation of land-ceiling legislation.”5 All of these privileged groups were largely comprised of Hindu upper castes.

The leaders of the “Congress system” sought to offset, and perhaps obscure, its bias toward traditional dominants and the social status quo with a vaguely socialist official rhetoric of state-led industrial development.6 The state thus occupied the “commanding heights” of the economy, with a monopoly over much of heavy industry and other “strategic” sectors, while the rest of the manufacturing economy was subjected to, and some would say shackled by, a pervasive system of government regulation, which over the decades came to be known in India as the license-permit Raj (a snide reference to British imperial rule in India, which was referred to as the Raj) . The license-permit system spawned vast patron-client networks linking politicians ...