![]()

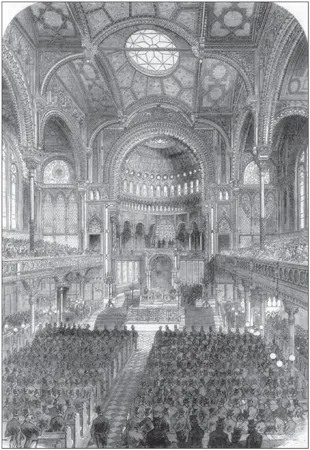

Opening of the New Jewish Synagogue, Berlin.

Source: The Illustrated London News (September 22, 1866).

CHAPTER ONE

An Architecture of Emancipation or an Architecture of Separatism?

Berlin

Das Bauwerk, will es Anspruch auf ein monumentales machen, muß vor allem national sein. Der deutsche Jude muß also im deutschen Staate im deutschen Style bauen.

(If a building intends to make a claim to monumentality, it first and foremost has to be national. A German Jew in a German state should therefore build in a German style.)

—EDWIN OPPLER (1864), quoted in Harold Hammer-Schenk, “Edwin Opplers Theorie des Synagogenbaus,” Hannoversche Geschichtsblätter 32, no. 1–3 (1979): 106

IN THE SUMMER of 1865, a full year before the completion of the Oranienburgerstraße synagogue in the center of Berlin, an anonymous letter appeared in the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums (AZdJ), the most widely read Jewish periodical in the German-speaking lands. Its author acknowledged the beauty of the new building emerging before everyone’s eyes and the “good taste” of those involved in the production of this magnificent synagogue (Prachttempel). Berlin, after all, he said somewhat snootily, “did not yet possess any religious buildings worth seeing” and this synagogue truly was an ornament to the Prussian capital. The author, however, questioned the usefulness and expediency of such a monumental structure. “The time has passed,” he argued, “when the majority of Jews are crowded in one district; a large contingent has moved to western neighborhoods and it would have been more appropriate and more conducive to religious attendance, had we built moderate-sized synagogues in a variety of districts as opposed to one excessively large one.”1 In Paris, he explained, two synagogues had been built in opposite neighborhoods, each of which amounted to one million francs, while in Berlin only one structure emerged at the extravagant cost of three and a half million francs. Emphasizing the latter’s impracticality—especially for Orthodox women living in western districts, for whom the walking distance of more than an hour was “too great of a sacrifice,” providing an “excuse” to stay home on the Sabbath—the Oranienburgerstraße building would achieve the very opposite end for which it was intended, namely a growing absence of Jewish worshippers. If this was indeed the case, concluded the author, then “surely it is worth posing the question to what purpose we have built at all?”

This question is central to our inquiry. While our author overestimated the extent to which the Berlin Jewish population had moved to better neighborhoods—the majority still lived in the Berlin Mitte district in the 1860s—it is true that the Oranienburgerstraße synagogue was built in a residential area that prosperous Jews were beginning to leave behind. Moreover, the community financed what was at the time the most expensive and largest synagogue in the world, surpassing those built in western European capitals, where Jews generally enjoyed more civil rights and liberties than was the case in Prussia. Drawing public attention by means of a conspicuous building in a bold Oriental design countered the approaches to synagogue building seen in London, Amsterdam, and Paris. Why and for what purpose Berlin Jewry erected a spectacular Moorish structure in the old city center, then, are legitimate questions to which our contributor to the AZdJ found only partial answers.

To him the incentives for monumental synagogue architecture lay in “the pleasure of building itself,” even if this meant the Jewish community would shoulder a heavy debt. “It is just the way things are nowadays,” he wrote, “to ask with every enterprise ‘where do we obtain the money?’ rather than ‘who will pay it back?’ ”2 Building extravagantly for the sake of extravagance, in other words, seemed to be the primary factor driving synagogue architecture in Berlin. While there might be some truth to his claim—large-scale building projects were increasingly common in Europe due to industrialization, population growth, and the expansion of the building industry—it is a simplistic answer to a complex question. We have to take into account, for instance, the fact that the Oranienburgerstraße project was initiated in the mid-1850s, at a time when Jewish residential migration was the exception rather than the rule and when the construction of one large house of worship in Berlin Mitte was the most logical choice. The Jewish community was also in desperate need of a large space, as the existing communal synagogue in the Heidereutergasse, with its 500 seats, and the Notsynagoge (auxiliary synagogue) in the Großen Hamburgerstraße, with space for an additional 1,800 worshippers, had ceased to be adequate much earlier. More than 13,000 Jews lived in the Prussian capital in the 1850s, and every year during the High Holidays the lack of space became more pressing. Furthermore, we have to consider the socioeconomic position of the congregation, which, despite the exorbitant construction costs of the synagogue, was prosperous enough to shoulder this debt as well as that of additional building projects, such as the Jewish hospital (also located in the Oranienburgerstraße). For a community that was financially comfortable, that did not need to spend a significant proportion of its communal budget on poor relief—as was the case in Amsterdam—and that strove for bourgeois respectability, building a monumental synagogue was not an irresponsible enterprise.

But the most important force driving this project was the legal status and the sociopolitical ambitions of the community. This determined to a great extent the size, location, style, and interior floor plan of the synagogue. While the building was inaugurated in the fall of 1866, its conception and design originated in the mid-1850s, when the community designated the Oranienburgerstraße plot for the location of the new synagogue and when the Protestant architect Eduard Knoblauch submitted his first set of drawings. As we shall see, this was a time of postrevolutionary tensions and political ambiguities, especially with regard to the legal status of the Jews. The 1848–1849 revolution had not solved the question of Jewish status in Prussia. Indeed, argued the historian Werner Mosse, the revolution had “retarded political emancipation.… Its failure, if anything, meant a temporary re-affirmation in many places of the doctrine of the Christian State.”3 Despite the growing volume of liberal voices, legislation granting equality to the Jews failed, leaving the matter “at an intermediate stage that was not free of ambiguities.”4 That Berlin Jewry proposed a massive building program precisely at a time when emancipation was in close reach but again obstructed is therefore no coincidence. It needed to make a strong appeal, a strong public statement that forcefully communicated its presence and its claim to citizenship. Now that it had the financial means and municipal permission to do so, Jewish leadership did not hesitate to build their Prachttempel. The Oranienburgerstraße synagogue was therefore a demand for emancipation rather than its consequence.

The new building and German synagogue architecture at large cannot be interpreted outside of the context in which both took shape. They were part and parcel of the prolific intellectual, cultural, and literary milieu of nineteenth-century German Jewry, the roots of which lie in the persistent illiberalism of the German states and the lasting power of aristocratic conservatism. Precisely because German Jews (contrary to their Dutch, English, and French counterparts) had to justify political emancipation, they produced a large body of books and journals, pamphlets and petitions that were rich in self-observation and in presenting “evidence” of Jewish progress. Ironically, the reconfirmation of Jewish difference after each failed attempt to eliminate legal restrictions only stimulated intellectual productivity aiming to disprove this difference, which further distinguished German Jewry from its gentile counterparts. The new synagogue was the aesthetic representation of this quest, another vehicle to press the claim for equality. In almost every way, the building “proved” that German Jews had become gebildete Bürger. Its design, for instance, attested to the Jews’ architectural sophistication; the organ—although hidden from view—announced the Jews’ willingness to modernize their religious practices; the fixed pews facing the lectern confirmed the congregation’s dedication to silent etiquette; and the visibility of the golden dome demanded that Berliners face the reality of a permanent Jewish presence in their midst. “[German Jews] have had and must continue to fight, step by step, for civil equality and for their recognition in life and society,” wrote the AZdJ in 1863.5 A monumental synagogue was a powerful weapon with which to fight this battle.

Indeed, Jewish political discourse at the time of the synagogue’s conception and construction reveals skepticism of and frustration with Prussian promises. The record of Prussian politicians had not been particularly reassuring and while progress had been made over the course of the nineteenth century, Jews were still disadvantaged and political emancipation was still incomplete. When reforms passed legislation, they were often ignored in practice.6 “I shouldn’t have to be the first one to tell you more perceptive [readers],” wrote an anonymous contributor to the AZdJ in 1866 on the subject of German Jewry’s political struggles, “that it would be a terrible self-deception to think that Judaism and its confessors have reached a final stage in their varied histories and henceforth will follow only one straight, smooth path along which they will be able to determine their own fate.”7 Legal emancipation was not a given, not an inevitability that lay just around the corner. It was not time that produced great achievements, preached Abraham Geiger in the newly inaugurated synagogue, but rather the actions of dedicated individuals. It was therefore the task of Berlin Jews themselves to ensure progress was made.8 Achieving full equality required a proactive stance on the part of Prussian Jewry and building a landmark synagogue was one way to advance its claim. The Oranienburgerstraße building thus simultaneously refuted and confirmed the still fragile, unresolved political status of German Jews.

The Berlin structure, then, sought the public limelight. It emerged in a milieu dramatically different from that of western Europe and consequently we cannot ascribe to it similar meanings. Lindsay Jones’s theory on the human experience of architecture, which emphasized the triangular interrelationship among building, human actors, and historical context in the production of meaning, demonstrated that an analysis of synagogues needs to include proper attention to space and place. Simply put, to understand what these buildings meant for Jews, we need to situate them in their local environment. A new synagogue meant something different for a Jew in 1860s Berlin than it did for a coreligionist in London precisely because they lived in different circumstances. Both Jews probably agreed that their new buildings were a necessity due to population growth and a lack of available space. Both Jews mostly likely reveled in their new buildings’ beauty, proudly displaying pictures of it in their living rooms or sending postcards to friends and family. But what was “beautiful” in the eyes of the Berliner, that is, Moorish monumentality, was presumptuous and inappropriate to the Londoner; what was desirable to Prussian Jews, namely to draw public attention to their presence by building in an utterly foreign architectural style, was undesirable—even nonsensical—to their English counterparts. As we shall see, Victorian Jews considered modest, familiar architectural expressions a means to convey respectability and assimilability; blending into the urban landscape meant blending into Victorian society. This strategy would not work for Prussian Jews. They had practiced inconspicuousness many times with only mediocre results. Now that they had attained bourgeois status and had lived up to gentile demands to acculturate, the Jews of Berlin were ready to show their achievements to the public. They did so by constructing the largest synagogue of its time, a bold initiative that directly defies the common claim that passivity and timidity were the primary characteristics of nineteenth-century Prussian Jewry.

That the project contained an overt political dimension became clear before the first stone was even laid and before Knoblauch had submitted his first designs. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, the Gemeinde asked permission to erect a second community synagogue, a request that involved the city authorities and the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The correspondence that followed, in which the Jews were granted permission to build, but only in a remote area away from where most Jews resided, revealed an unwillingness on the part of the Berlin authorities to acknowledge a public and a central Jewish presence.9 After the synagogue was completed, too, the political component remained conspicuous, not merely in the aesthetics of the building, but also in the response of gentile observers. The latter admired and appreciated the architectural sophistication of the synagogue but still considered it a Fremdkörper, a foreign body in their city—a sentiment revealed in the language used to describe the building. It was “like a fairy-tale,” exotic, and entirely un-German, confirming for many the inherent foreignness of the Jews.

Before we explore this further, however, let us first turn to the city of Berlin, for its urban and architectural development set the scene in which the Oranienburgerstraße synagogue was constructed.

Berlin in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century

Many observers of Berlin have wondered how this rather shabby garrison town grew to such importance in the history of Prussia and Germany. Its curious location in the swampy areas between the Elbe and Oder rivers and its lack of easy access to a large port rendered it an unlikely candidate to become one of the world’s leading capitals by the late nineteenth century. The rather poor quality of the soil rendered the area unattractive to large numbers of people. Indeed, the Prussian landscape was so unpromising that the French writer Stendhal (1783–1842) once asked what possibly “could have possessed people to found a city in the middle of all this sand?” In addition to its geographical challenges, Berlin was recurrently weakened by conflict and an unstable economy over the course of its long history. While the ascendancy of the Hohenzollern dynasty in the sixteenth century sl...