- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

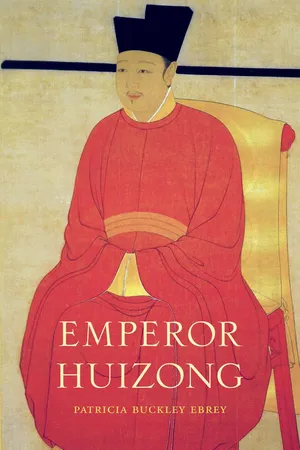

Emperor Huizong

About this book

China was the most advanced country in the world when Huizong ascended the throne in 1100 CE. In his eventful twenty-six year reign, the artistically-gifted emperor guided the Song Dynasty toward cultural greatness. Yet Huizong would be known to posterity as a political failure who lost the throne to Jurchen invaders and died their prisoner. The first comprehensive English-language biography of this important monarch, Emperor Huizong is a nuanced portrait that corrects the prevailing view of Huizong as decadent and negligent. Patricia Ebrey recasts him as a ruler genuinely ambitious—if too much so—in pursuing glory for his flourishing realm.

After a rocky start trying to overcome political animosities at court, Huizong turned his attention to the good he could do. He greatly expanded the court's charitable ventures, founding schools, hospitals, orphanages, and paupers' cemeteries. An accomplished artist, he surrounded himself with outstanding poets, painters, and musicians and built palaces, temples, and gardens of unsurpassed splendor. What is often overlooked, Ebrey points out, is the importance of religious Daoism in Huizong's understanding of his role. He treated Daoist spiritual masters with great deference, wrote scriptural commentaries, and urged his subjects to adopt his beliefs and practices. This devotion to the Daoist vision of sacred kingship eventually alienated the Confucian mainstream and compromised his ability to govern.

Readers will welcome this lively biography, which adds new dimensions to our understanding of a passionate and paradoxical ruler who, so many centuries later, continues to inspire both admiration and disapproval.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. Growing Up in the Palace, 1082–1099

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Maps, and Illustrations

- Preface

- Note on Ages, Dates, and Other Conventions

- Chronology

- Cast of Characters

- Genealogy of the Song Emperors and Empresses

- I. Learning to Rule, 1082–1108

- II. Striving for Magnificence, 1102–1112

- III. Anticipating Great Things, 1107–1120

- IV. Confronting Failure, 1121–1135

- Afterword

- Color Plate Section

- Appendix A: Reasons for Rejecting Some Common Stories about Huizong and His Court

- Appendix B: Huizong’s Consorts and Their Children

- Timeline

- Notes

- References

- Chinese Character Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app