![]()

1

The Near East on the Eve of Islam

The roots of the religion of Islam are to be found in the career of a man named Muhammad ibn ʿAbd Allah, who was born in Mecca, a town in western Arabia, in the latter part of the sixth century C.E. Arabia at this time was not an isolated place. It was, rather, part of a much wider cultural world that embraced the lands of the Near East and the eastern Mediterranean. For this reason, to understand the setting in which Muhammad lived and worked and the meaning of the religious movement he started, we must first look far beyond his immediate surroundings in Mecca.

Muhammad lived near the middle of what scholars call “late antiquity”—the period from roughly the third to the seventh or eighth centuries C.E.—during which the “classical” cultures of the Greco-Roman and Iranian worlds underwent gradual transformation. In the Mediterranean region and adjacent lands, many features of the earlier classical cultures were still recognizable even as late as the seventh or eighth century, albeit in new or modified form, while others died out, were changed beyond recognition, or were given completely new meaning and function. For example, in the sixth century C.E. the literate elites of the lands of the old Roman Empire around the eastern Mediterranean still cultivated knowledge of Greek philosophy and Roman law and of Greek and Latin literature, even though the pursuit of these arts was less widespread and often dealt with new and different issues than in Roman times. At the same time, most people had by this time given up their former pagan cults for Christianity. Similarly, the public and civic rituals of classical times, focused on the amphitheatre, the public bath, and the performance of civic duties, were beginning to atrophy—especially in smaller towns—and, after the fifth century, were gradually being replaced by more private pursuits of a religious and introspective kind. With the spread of Christianity in the eastern Mediterranean lands came also the emergence—alongside Greek and Latin—of new liturgical, and eventually literary, languages such as Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Ethiopic, which had formerly been unwritten. We can see in retrospect, then, that the late antique period in the eastern Mediterranean was one of transition between the preceding classical era, with its well-articulated civic life and Greco-Latin focus, and the subsequent Islamic era, with its emphasis on personal religious observance and the development of a new literary tradition in Arabic.

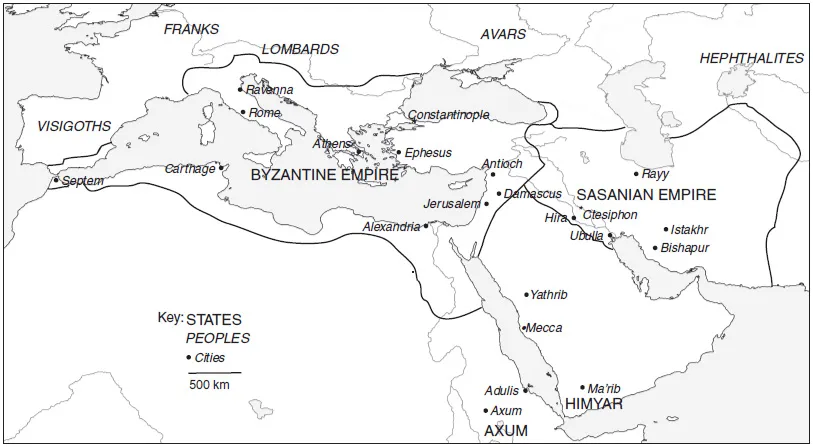

Map 1. The Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, ca. 565 C.E. (borders approximate)

The Empires of the Late Antique Near East

In the latter half of the sixth century C.E., the Near East and Mediterranean basin were dominated politically by two great empires—the Byzantine or Later Roman Empire in the west and the Sasanian Persian Empire in the east. The Byzantine Empire was actually the continuation of the older Roman Empire. Its rulers called themselves, in Greek, Rhomaioi—“Romans”—right up until the empire’s demise in 1453. For this reason it is also sometimes called the “Later Roman Empire,” but I shall refer to it here as the Byzantine Empire, after Byzantium, the village on the Bosporus on which the capital city, Constantinople, was founded.

In the late sixth century, the Byzantine Empire dominated the lands on the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean basin (today’s Turkey, Syria, Egypt, and so on). The other great empire, that of the Sasanians, was centered on the mountainous Iranian plateau and the adjacent lowlands of what is today Iraq, the rich basin of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Just as the Byzantines preserved the Roman heritage, the Sasanians were heirs to the long imperial traditions of ancient Persia. Most of the vast region from Afghanistan to the central Mediterranean was under the direct rule of one or the other of the two empires. Even those areas in the region that were outside their direct control were either firmly within the sphere of influence of one or the other power or were the scene of intense competition between them for political allegiance, religious influence, and economic domination. This contested terrain included such areas as Armenia, the Caucasus, and, most important for our purposes, Arabia. A third, lesser power also existed in the Near East—the kingdom of Axum (sometimes Aksum). The Axumite capital was situated in the highlands of Ethiopia, but Axumites engaged in extensive maritime trade from the port city of Adulis on the Red Sea coast. By the fourth century, Axum had been converted to Christianity and for that reason was sometimes allied with Byzantium; but in general our knowledge of Axum is very limited, and in any case, Axumite culture did not contribute much to Islamic tradition, whereas both Byzantium and Sasanian Persia did. Hence, most of our attention hereafter will be devoted to describing the Byzantine and Sasanian empires.

The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine emperors ruled from their capital city at Constantinople (modern Istanbul) on the Bosporus; the city was dedicated in 330 C.E. by the Roman emperor Constantine as the “Second Rome.” From Constantinople, the Byzantine emperors attempted to hold their far-flung possessions together through military action and a deft religious policy. The Byzantine emperors subscribed to a Christianized form of the vision of a united world order first advanced in the West by Alexander the Great (d. 323 B.C.E.) and later adopted by the Romans. Those who held to the Byzantine variant dreamed of a universal state in which all subjects were loyal politically to the emperor and religiously to the Byzantine (“Orthodox”) church headed by the patriarch of Constantinople, in close association with the emperors.

JUSTINIAN’S EDICT OF 554 C.E. TO THE PEOPLE OF CONSTANTINOPLE, NOVEL CXXXII

We believe that the first and greatest blessing for all mankind is the confession of the Christian faith, true and beyond reproach, to the end that it may be universally established and that all the most holy priests of the whole globe may be joined together in unity. . . .

The Byzantine emperors faced at least two main problems—over and above the challenge of their Sasanian rival—in trying to realize this vision. The first problem was maintaining the strength and prosperity of the vast territory they claimed to rule, and their effective control of it, given the rudimentary technologies of communication and management available in that age—in short, the problem of government. In its heyday during the first century B.C.E. and first century C.E., the Roman Empire had extended from Britain to Mesopotamia and Egypt, a span of roughly 4,000 kilometers (km), or 2,500 miles (mi). It included people speaking a dizzyingly wide array of languages—Latin and Greek in many cities around the Mediterranean, Germanic and Celtic dialects in Europe, Berber dialects in North Africa, Coptic in Egypt, Aramaic and Arabic in Syria, Armenian and Georgian and dozens of other languages in the Caucasus and Anatolia, and Albanian and Slavic dialects in the Balkans. The sheer size of the empire had caused the emperor Diocletian (284–305) to create a system of two coordinate emperors, one in the west and one in the east—so that each could better control his respective half of the empire, suppressing efficiently any uprisings or unrest in his domain and warding off any invasions from the outside. However, during the fourth and fifth centuries, the invasions and migrations of the Germanic peoples and other “barbarians,” such as the Avars and the Huns, were simply too much for the emperors in Italy, who were overwhelmed by them. By the early sixth century, much of the western half of the empire had become the domains of various Germanic kings—the Visigoths in Spain, the Vandals in North Africa, the Franks in Gaul, the Ostrogoths in Italy. Paralleling this political disintegration was a widespread economic contraction in many of the western Mediterranean lands.

Land Walls of Constantinople. The city’s magnificent defenses, still impressive today, permitted it to withstand the onslaughts of many enemies from the fourth until the fourteenth century C.E.

The eastern half of the empire, by contrast, managed to live on as a political entity, and its economy remained much more vibrant than that of the West. The Byzantine emperors in Constantinople, despite some close calls at the hands of the Avars, Bulgars, and Slavs, were able to ward off repeated barbarian onslaughts. Moreover, they always thought of themselves as the rightful rulers of the former empire in its full extent. Some even dared to dream of restoring the empire’s glory by reclaiming lost lands in the west. This was especially true of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I (ruled 527–565)—who, depending on one’s point of view, might be considered either “The Great” or merely megalomaniac. Justinian marshaled the full power of the Byzantine state, including its powers of taxation, in an attempt to reconquer the lost western provinces. His brilliant general Belisarius did in fact succeed in reestablishing Byzantine (Roman) rule in parts of Italy, Sicily, North Africa, and parts of Spain. Justinian also spent lavishly on great buildings, of which the magnificent church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople is the finest surviving example. But the cost of this was high, as his efforts to restore Rome’s lost glory through conquest and construction left the empire’s populations impoverished and resentful, its treasury depleted, and its armies stretched thin.

Urban centers in the eastern Mediterranean were much stronger than those in the West, where cities had almost vanished, but their prosperity was also weakened during the late sixth century. One factor was a series of severe earthquakes that shook the eastern Mediterranean lands repeatedly in this period; another was the plague. Plague, which arrived in the 540s and returned every several years thereafter, regularly harvested off part of the population and further sapped the empire’s ability to recover its vitality. By the late sixth century, the Byzantine Empire was ripe for devastating onslaughts by the Sasanians—the final chapters in the long series of Roman-Persian wars stretching back to the first century C.E. Resurgent under their powerful great king Khosro I Anoshirwan (ruled 531–579), the Sasanians attacked the Byzantine Empire several times during the 540s and 550s. They invaded Byzantine-controlled Armenia, Lazica, Mesopotamia, and Syria and sacked the most important Byzantine city of the eastern Mediterranean, Antioch. Later, starting in 603, the Sasanian great king Khosro II Parviz (ruled 589–628) launched an even more devastating attack that resulted in the Persian conquest of Syria, Egypt, and much of Anatolia. Like the attacks of the mid-sixth century, that war was possible in part because the Byzantine Empire was in a weakened state.

Hagia Sophia. Justinian’s great church in Constantinople, dedicated to “Holy Wisdom,” symbolized the intimate nexus between the Byzantine emperor and the church.

Sinews of empire: A surviving stretch of Roman road in northern Syria. Built to facilitate the movement of Roman legions, these roads not only permitted the emperors to send troops promptly to distant provinces but also served as vital ways for overland commerce.

The other major challenge faced by the Byzantine emperors between the third and seventh centuries had to do with religion. In 313 C.E., Emperor Constantine I (ruled 306–337) declared Christianity a legal religion in the Roman Empire in the Edict of Milan; it was established as the official faith by Emperor Theodosius I (“The Great,” ruled 379–395). Since that time, the emperors had dreamed of realizing the vision of an empire that was not only universal in its extent but also completely unified in its religious doctrine—with the Byzantine emperor himself as the great patron and protector of the faith that bound all the empire’s subjects, both to one another and in loyalty to the state and emperor. In the earlier Roman Empire, the official cult of the deified emperor had served this purpose, while allowing people to continue to worship their local pagan gods as well; but when Christian monotheism became the empire’s official creed, the emperors demanded a deeper, exclusive religious obedience from their subjects.

This dream of religio-political unity, however, proved impossible to attain. Not only did diverse groups of pagans, Jews, and Samaritans in the empire stubbornly resist Christianity; even among those who recognized Jesus as their savior, there arose sharp differences over the question of Christ’s true nature (Christology) and its implications for the individual. Was Jesus primarily a man, albeit one filled with divine spirit? Or was he God, essentially a divine being, merely occupying the body of a man? Since he died on the cross, did that mean that God had died? If so, how could that be? And if not, how could it be said that Jesus died at all? Since Christians believed passionately that their very salvation depended on getting the credal formulation of such theological issues right, debates over Christ’s nature were intense and protracted. In the end, it proved impossible to resolve these issues satisfactorily, even though the emperors expended a great deal of thought, money, and their subjects’ good will in the effort to mediate disputes in search of a theological middle ground acceptable to all sides. It must also be said that these debates over doctrine often pitted powerful factions within the church against one another for reasons that were as much personal and political as doctrinal. Particularly important in this respect was the old rivalry between the patriarchs of the ancient sees of Alexandria and Constantinople, though the bishops of Rome, Antioch, and other centers also played a part.

Orthodoxy thus came to be defined through a series of church councils—intensely political gatherings of Christian bishops, sometimes supervised by the imperial court—that, among many other items of business, successively declared specific doctrines to be heresies. The result was that by the sixth century, the Christians of the Near East had coalesced into several well-defined communities, each with its own version of the faith. The official Byzantine church—“Greek orthodox,” as it is called today in the United States—was, like the Latin church in Rome, dyophysite; that is, it taught that Christ had two natures, one divine and one human, which were separate and distinct but combined in a single person. (This separation enabled them to understand Christ’s crucifixion as the death of his human nature, while his divine nature, being divine, was immortal.) Byzantine Orthodox Christians were predominant in Anatolia, the Balkans, Greece, and Palestine, and in urban centers elsewhere where imperial authority was strong. On the other hand, in Egypt, Syria, and Armenia most Christians, particularly in the countryside, were monophysite, that is, they belonged to one of several churches that considered Christ to have had only a single nature that was simultaneously divine and human. (From their perspective, the key point about Christ was that in him God had truly experienced human agony and death, but being God he was able to rise from the dead.) The emperor’s efforts to heal this rift by convening the Council of Chalcedon (451) backfired when the resultant formula was rejected by the monophysites, who clung tenaciously to their creed despite sometimes heavy-handed efforts by the Byzantine authorities to wean them of it. A third group, largely driven out of Byzantine domains by the sixth century but numerous in the Sasanian Empire and even in Central Asia, were the Nestorians, named after Bishop Nestorius of Constantinople, whose doctrine was condemned at the Council of Ephesus in 431. Although dyophysite, the Nestorians placed, in the eyes of both the “orthodox” Byzantine church and the monophysites, too much emphasis on Christ’s human nature and understated his divinity. North Africa was home to yet another sect deemed heretical, the puritanical Donatists, who rejected any role of the Byza...