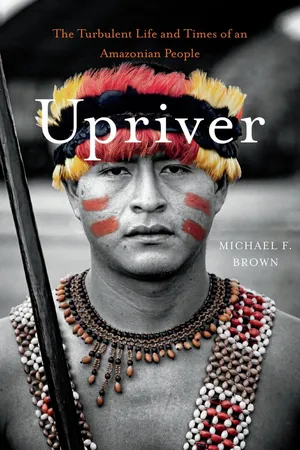

![]()

PART ONE

1976–1978

Anthropology—a professional commitment to understanding different others—is always a reckless enterprise; and exposing how it is actually done, more reckless still.

—Inga Clendinnen, “The Power to Frustrate Good Intentions”

![]()

1

Andean Prelude

Morning fog blanketed the trail rising out of Molinopampa, a village on the eastern flanks of the Andes in northern Peru. Both sides of the rutted path were lined with cloud forest vegetation: towering ferns and gnarled, moss-covered trees from which bromeliads swayed like silvery apparitions. In the distance, it was possible to make out rolling bogs stippled with low hummocks of grass. Molinopampa’s plank-sided houses gradually faded into the mist below.

I toiled up the track at the rear of a packtrain led by two Andean women, Sonia and Carmen, plus a boy brought along as their helper. They had reluctantly allowed me to accompany them to a remote village called Quinjalca, to which they were returning after working in Lima for several years. Sonia and Carmen knew the trail; I didn’t.

Just after dawn I’d been introduced to them by the owner of the shabby pensión where I had passed the night. “The ingeniero wants to find people who still speak Quechua,” he explained. Sonia and Carmen were loading two horses and a mule with focused attention. They carefully divided the cargo into portions of similar weight for balance, then lashed it to pack frames with plaited wool cords. They were wary. The unspoken issue was fear of pishtacos, ghoulish hunters of human body fat. Andean people believed that pishtacos resembled tall, fair-haired, bearded, blue-eyed gringos, a decent match for me. High-country trails were a pishtaco’s hunting ground. In the end, local rules of courtesy to fellow travelers prevailed, and I was allowed to fall into step behind them as they left the village.

The ascent was hot work. When we stopped to rest, Sonia and Carmen kindly shared provisions, but their reticence remained firmly in place. A raw wind cooled us, then drove us back into motion. Another hour of climbing brought us to a plain, called a puna in these parts. The trail wove between marshy areas of reeds and bunchgrasses where cattle browsed and wallowed. Mud sucked at our feet and slowed the horses. They became balky and threw their loads, which had to be retied. After another short rise, the trail dropped into a narrow valley. Clinging to the nearest of its steep sides was Quinjalca, a scatter of crumbling adobe houses roofed with barrel tiles. Not long after midday my companions left me in front of the police post on the patch of bog that served as the village plaza.

In those days foreign travelers were obliged to register with Peru’s paramilitary police force, the Guardia Civíl, when staying overnight in the towns and villages of the interior. The GC office in Quinjalca had the look of a punishment post, and so it proved to be. The mournful sergeant and his two men each eventually admitted to some blunder or lapse of discipline elsewhere that had gotten him assigned to this remote village, so far from running water, electric lights, or an unattached woman who might be receptive to male attention. The sergeant offered me a place to bunk down for the night, which solved the problem of how he would keep an eye on a mysterious visitor.

A gaggle of village boys, all dressed in identical brown homespun ponchos, pointed me to the village school. The teachers insisted that Quechua-speakers had mostly died off and that traditional Andean customs were in decline. Families were abandoning played-out fields for dreams of prosperity in the rainforest frontier to the east. They said that Olleros, a still more remote village across the valley, was the place to find old-timers who spoke Quechua. Having been told some version of this story every day for the past two weeks, I was doubtful.

That night I buried myself under thick blankets provided by my hosts. The sergeant slept elsewhere, and I shared quarters with his two men, like me bachelors in their twenties. We swapped stories to pass the time. In Quinjalca, the biggest crime problem was cattle rustling. Several months before, a local farmer had found a deserted hut well stocked with food—a rustler’s hideout. One of the cops spent a miserable night there, shivering in his poncho, service revolver in hand, without fire or lantern. No rustler appeared. The next night it was his partner’s turn. A suspect eventually arrived but managed to flee into the dark after being hailed. The storyteller laughed bitterly about this wasted sleuthing, then sought my advice about the best medicine for curbing a man’s sex drive.

Breakfast was taken in the house of a woman who cooked for visiting state employees. By midmorning I was descending from Quinjalca to the Río Imaza, which farther north becomes a formidable river that empties into the Alto Marañón and then the Amazon. The recent rains had given the river enough power to make fording it impossible on foot, forcing a half-hour detour to the valley’s only bridge. Ascending the valley’s other side, I reached Olleros at noon. After the near silence of Quinjalca, it was startling to hear conversation and laughter. The commotion came from the house of the village mayor, who was serving lunch to a group of eight or nine adults. After listening to my story, he invited me to eat. Lunch consisted of roasted guinea pig, astringent tubers called oca, boiled large-kernel corn called mote, and cooked cabbage.

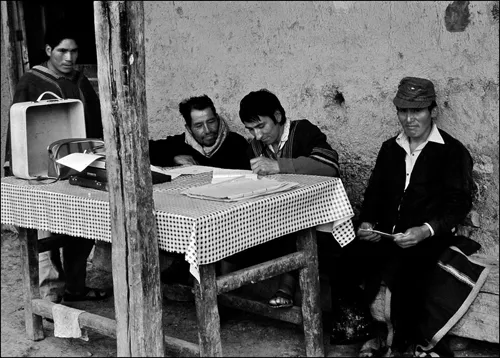

While the dishes were cleared, the mayor excused himself to attend to business. A table was brought outside. Someone produced a battered typewriter. A young man, the mayor’s nephew, laboriously typed a bill of sale for land that the mayor’s wife was purchasing from her widowed sister. The widow was moving to her son’s new farm in the Alto Río Mayo, jungle land that he had recently cleared. After spirited discussion about landmarks for the property’s boundaries—paths, stone walls, rows of trees, prominent boulders—the document was complete. Buyer and seller, both illiterate, sealed the transfer with fingerprints. Then someone yanked the stopper from a liter of aguardiente, a liquor made from sugar cane.

Drinking aguardiente in prodigious quantities was an essential element of Andean ceremonies then. It may still be, although the spread of evangelical Christianity in Peru has thrown the tradition’s future into doubt. The adulterated aguardiente consumed in places such as Olleros was only a step removed from paint thinner and had a less appealing bouquet. Its effect on a drinker’s judgment was rarely salutary.

As the shot glass was passed around, I asked whether people in the village still spoke Quechua. “Hardly anyone,” the mayor said. “Just a few old people. The younger ones are moving east to the jungle.”

The party took a maudlin turn. The two sisters began to weep, the sadness of their imminent separation sharpened by the alcohol. Dark clouds piled up at one end of the valley and spilled toward us. Soon it was pouring. A return to Quinjalca that day began to look doubtful, as did my ability to stand upright. Not to worry, the mayor said, there would be somewhere for me to sleep. The mayor’s nephew, a man named Leonidas, suggested that I visit him in Atumplaya, his new home on the Amazon frontier. “There are lots of real Indians, Aguarunas, who live nearby,” he said. “You’ll find all the natives you want near my farm.”

The mayor of Olleros (second from left) oversees preparation of a deed transfer, 1976. The aguardiente had not yet begun to flow.

Photograph courtesy of Michael F. Brown.

The mood soured as the rain hammered down. The mayor became inquisitive, then belligerent. He demanded my identity documents and insisted that the photograph in my passport showed someone else. I was carrying falsified papers, he said. I was a spy, an agent of the CIA. Another nephew, a young man named Roger, pulled me away. “You can stay at my family’s house, mister,” he said. The mayor’s face twitched as he pondered whether to throw a punch, if he could only stop swaying and get his bloodshot eyes to focus. No one but the mayor wanted a brawl. Roger led me away as fog closed in around us.

We stumbled down the hill to his grandmother’s kitchen, where a fire cast trembling light on soot-blackened walls. Guinea pigs scrabbled under a couple of benches. Roger’s grandmother, an elderly woman covered by countless layers of wool clothing, prepared us soup, roasted maize, and herbal tea. As I ate the piece of dried meat that she gave me, I noticed that the others were doing without. I felt both gratitude for her kindness and shame for being singled out this way.

Roger led me to a storage room with a thatched roof. In the darkness it was possible to make out a bed in the corner, a saddle and tools on the walls. Plaited garlic strands hung from the ceiling. Roger piled the bed high with blankets and said goodnight. Too wired on alcohol to sleep, I stood for an hour outside the storage shed, watching the fog roll past and listening to the soft percussion of rainwater dripping from the thatch. Waking once or twice during the long night, I experienced momentary disorientation because of the room’s absolute darkness.

In the morning Roger’s grandmother served breakfast. Again I was given meat, as well as a fried egg, while the others spooned down what appeared to be maize gruel. My hosts gossiped about the mayor, who had beaten his wife after our departure. “He does that a lot,” Roger explained. The brothers discussed whether to join a communal work party, called a minga, that was to begin shortly at the other end of the village. Flute and drum music announced that work was about to commence. They left to join their neighbors. The event would end with the serving of more cane alcohol. I thanked Roger’s grandmother and gave her a hundred soles, which seemed to please her.

My worn boots proved useless on the return to Quinjalca. I tumbled several times in the greasy mud, cursing. Near the bridge over the Imaza two fierce-looking dogs made for me with teeth bared, but they backed off when I grabbed a handful of stones. In a description of this area dating to the 1890s, the archaeologist Adolph Bandelier reported that these valleys were “perhaps the most broken and accidented country” he had ever seen. “Traveling there is almost an uninterrupted clambering up and down, and the valleys are so narrow that they might more appropriately be called gorges.”1

By midmorning I was back at the police post in Quinjalca watching another wave of rain sluice off the roof tiles. The next day, after retracing the trail to Molinopampa, I made my way to Chachapoyas, the region’s largest town. In 1945 the English botanist Christopher Sandeman said of Chachapoyas that “in spite of a large plaza, a cathedral of minor pretensions, a library, and some ten thousand inhabitants, the place is little more than an overgrown Indian village with open drains running down the middle of the cobbled streets and small, jerry-built adobe houses, vulnerable to even minor earthquakes, which are frequent here.” In the rainy season Chachapoyas was as sad as Molinopampa, only on a larger scale.2

The fruitless journey to Olleros was an attempt to salvage research that was foundering. I faced the prospect of returning to my university in the American Midwest as one of those wraiths about whom faculty and other graduate students spoke in funereal tones: the promising doctoral student whose project turned to dust.

My original plan, for which a private foundation had awarded me a modest research grant, had been to study the use of medicinal plants by the Lamistas, a native people whose widespread population was centered in the Upper Amazonian town of Lamas. I had come to know Lamas two years earlier while working in the central Andes with a team of archaeologists. We were based in the highest of the high country on the shore of Lake Junín, Peru’s second-largest lake. Our sleeping quarters were located at 14,300 feet above sea level. Even for fit young adults, the main challenge of each day was finding enough oxygen to sustain life. Altitude and bad food played havoc with digestion, regularly giving rise to a condition known as the “purple burps,” a noxious gastric detonation that made its victims unpopular in the small, windowless rooms where we bunked. The locals were outwardly friendly, but the appearance of graffiti promising “death to agents of the CIA” on the walls outside our lab showed that some harbored more complicated feelings.

During the field season I visited another research team working in Lamas. Like the area around Lake Junín, the terrain was mountainous, but a subtropical climate gave it a completely different feel. The lush vegetation was exhilarating. The locals seemed more relaxed and open than the Andean villagers I had encountered. The tropics worked their spell.

Lamas was a curious place that blended the Andean with the Amazonian. Richard Spruce, the great botanical explorer of the Amazon, spent time there in 1855. He described it as “a town of 6000 inhabitants, near the top of a conical hill, that reminded me of similarly situated towns and villages in Valencia.”3 In the 1970s, as in Spruce’s time, the town was ruled by a mestizo elite whose houses surrounded the inevitable plaza and Catholic church, as well as a town hall, schools, and small shops, all pastel-colored and made of adobe or cinder block. Away from the center were discrete neighborhoods—urban villages, really—occupied by Lamistas.

Lamista men were not especially distinctive-looking, although they were more likely than mestizos to be seen walking barefoot and carrying enormous bales of cotton or bags of coffee beans on their backs, their hands braced on cotton tumplines stretched taut by the weight of their burdens. Lamista women were unmistakable, however. All but the youngest girls wore embroidered white or blue cotton blouses and full, pleated black skirts from which they hung brightly colored scarves at rakish angles. Necklaces of heavy gold-plated beads, metallic hair clips, and multicolored hair ribbons formed a brilliant ensemble. Religious holidays brought forth even more flamboyant color.

Lamista woman, 1976.

Photograph courtesy of Michael F. Brown.

Despite the relative accessibility of Lamas and the size of the Lamista population, then greater than fifteen thousand, little was known about them. They were nominally Catholic, but their social separateness was marked by worship of a patron saint different from that of the town’s mestizos. Lamista men enjoyed fame in the region for their tenacity as cargadores who could move enormous loads through the cruelest terrain. They were also respected for their knowledge of healing plants and sorcery. In the colonial period, the arrow poison made by Lamistas was so coveted that merchants used it as a form of currency. Their neighborhoods were said to be organized around extended families that feuded among themselves.4

Lamistas spoke a regional dialect of Quechua, a language usually associated with descendants of the Incas. For reasons still not completely understood, some rainforest peoples abandoned Amazonian languages in favor of Quechua, and it is now spoken by indigenous Amazonian groups in Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. It seemed likely that the Lamistas descended from demoralized rainforest tribes, thinned by European arms and epidemics, who had been gathered together in missionary enclaves to exploit their labor and promote Christianization.5

An inescapable feature of the town was mestizo domination of Lamista economic life. Mestizo buyers of Lamista coffee, cotton, and maize routinely paid Indians less than market rates. By extending credit to Lamistas for the purchase of basic goods, patróns lured them into a web of debt passed from generation to generation. The predatory nature of the relationship was softened slightly by the custom of asking patróns to serve as godfathers to Lamista children, but this also bound the Lamistas more tightly to a system designed to exploit their labor.

For all that, few patróns appeared wealthy by American standards or even by those of middle-class Lima. Lamas was a poor province, its economy subject to unpredictable fluctuations in the price of cotton and coffee. The handful of patróns w...