![]()

Part I

Solomon the Wise King

![]()

Story 1

The Fisherman and the Genie

AN OLD FISHERMAN LIVING IN great poverty with a wife, his son and two daughters, throws his net into the sea one moonlit night, and has no luck: his first haul is the carcass of a donkey, his second an old jar full of sand and clay, his third a heap of bits of glass and pottery, bones and débris. In between each throw of his net, he rails against fortune and passionately laments his state:

‘Here virtue cries for misery, and the good-for-nothing disguises himself in his kingdom. The bird that soars high exhausts itself from west to east, while the canary in its cage feasts on sweets.’

He then looks up at the sky, sees dawn is beginning to break and prays that his fourth and last attempt will bring his family something to eat from the sea, in the same way as God made it obey Moses.

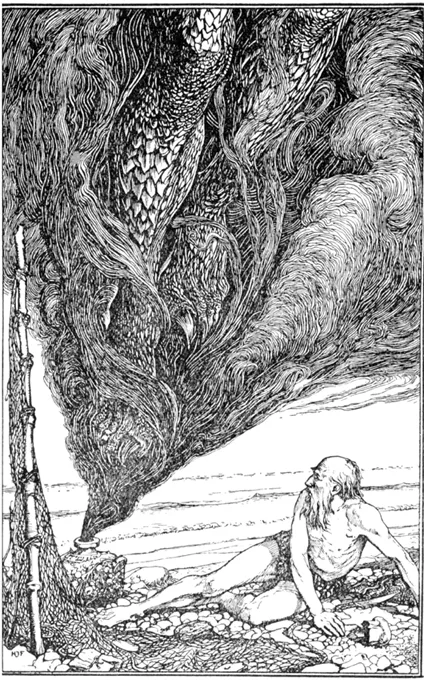

This time, he fishes up a copper bottle, sealed with a lead stopper, and is overjoyed because the copper will fetch at least six gold dinars which he can use to buy wheat. Before setting out for the market, he decides he must open it, and as he chisels away at the lead with his knife, smoke starts rising up and up, and darkens the blue of the morning sky before it rolls down to the ground again, gathers itself together to a great rumble and takes the form of a huge afrit: ‘his head, as high as a dome, touched the clouds, while his feet rested on the ground. His hands resembled gigantic pitchforks, his legs the mast of a ship, his ears shields, his mouth a cavern, his teeth rocks, his nose a jar, his nostrils trumpets, his eyes torches. He had a mane of hair, all tangled and dusty. A real monster!’

The fisherman is seized by a terrible fear, as he hears the jinni – for it is a jinni, of the fearsome species of the afrits – cry out a profession of faith in the true God and in Solomon his prophet, and promise that he will never disobey him again. The fisherman reproaches him, telling him Solomon has been dead more than 1,800 years: ‘We are living at the end of time,’ he says, and demands to know his story.

The jinni tells him to rejoice; but he is being cruelly ironic for with his next breath he informs the fisherman that the hour of his death is at hand, and he must choose the method and the tortures he shall suffer.

The fisherman protests: he has delivered him from the bottle, and is to be rewarded by a terrible death?

‘Listen to my story,’ orders the afrit. He then tells the fisherman: ‘Know that I am a heretical demon. I refused to obey Solomon, son of David. My name is Sakhr.’ He relates how he was brought before Solomon by his vizier and ordered to embrace the true God, but persisted in his refusal, and so was captured and sealed up inside the flask with the lead stopper, inscribed with the name of the true God, and thrown by the faithful jinn to the bottom of the sea. There a hundred years passed, and the jinni promised to bring riches to his deliverer. No one saved him, and another hundred years passed, and he swore to make his rescuer even richer. Another four hundred years passed, and by this time the jinni inside the bottle had become so enraged, he swore that he would kill anyone who freed him now.

The fisherman begs for mercy, but his enemy remains obdurate.

‘O master of demons,’ cries out the fisherman. ‘Is this how you return evil for good?’ He recites a pious proverb which warns against such behaviour – and adds an allusion to the fate that overtakes the ungrateful hyena in a beast-fable.

‘Stop dreaming,’ says the implacable jinni. ‘You have to die.’

The fisherman reminds himself that unlike this jinni, he is a human being, endowed with reasoning powers; he can work out a stratagem.

He invokes the name of God as engraved on the ring of Solomon and pledges the afrit to answer a question truthfully. His antagonist is agitated at the invocation of God and the ring, and agrees. The fisherman then asks him how he got into the bottle, since even one of his hands and feet would not fit.

‘I’ll only believe it when I see it with my own eyes,’ says the fisherman.

(It is the end of the third night in the cycle, and Shahrazad breaks off: with the dawn she must stop. But the Sultan wants to hear what happens next and so she is reprieved for another day – and night.

On the fourth night, she resumes her tale.)

The fisherman watches the jinni shake himself all over and turn back into smoke which rises to heaven and then gathers together and enters the flask. From inside Sakhr calls out:

‘You see, fisherman, I am inside the flask. Do you believe me now?’

The fisherman rushes to seize the flask and the stopper of lead imprinted with the seal of Solomon, and stuffs it back into the mouth of the bottle.

Now it is his turn to give the order that the jinni must die. He is going to throw him into the sea, he says, and build himself a house on the spot so that nobody else can fish there. The jinni struggles in vain to free himself, but he finds himself once more a prisoner of the seal of Solomon.

‘No, no,’ he cries out as his jailer walks towards the sea.

‘Yes, yes,’ replies the fisherman.

The rebel afrit tries to cajole him, sweetly and softly, and promises him wealth and blessings. But the fisherman does not believe his protestations. He knows another story about kindness rewarded with death, and it has made him wary.

And Shahrazad begins to tell the story of the fisherman telling that story . . .

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Master of Jinn

I

THE FAMOUS TRICKSTER TALE OF ‘The Fisherman and the Genie’, at once alarming and funny, so satisfying in its (first) neat resolution when the pauper outwits the colossus, the enemy is hoist on his own petard, and the jinni inveigled back into the bottle, has rightly enjoyed a long and celebrated history (it was successfully restaged in the Disney Aladdin, with Robin Williams voicing the genie). But when Sakhr remembers the scene of his rebellion and punishment at the hands of Solomon, his story provides the fundamental background plot for the cosmology of the Arabian Nights, in which the wise king plays a pre-eminent role as master of the book’s magic, with the jinn at his command.

Unlike the biblical king, the Muslim Solomon understands the language of beasts and birds and commands the winds and the elements; he rules over the higher order of angels and, above all, is given mastery over the innumerable spirits, the jinn, who exist invisibly alongside angels, humans and animals and form a distinct order of beings, elemental and mortal, metamorphic physically and morally, shifting between states of visibility and invisibility, capable of redemption and goodness yet for the most part, especially in the stories of the Nights, capricious, arbitrary and amoral. The stories of the Nights take these aspects of Solomon for granted, and treat them to no exclamations of wonder, giving the impression that these qualities of his were generally known by the community of listeners as well as by the makers of the literature. There is, however, so much common ground between the Judaeo-Christian tradition about the wise king and the Islamic and other Eastern material that it would be too blunt to argue simply that something intrinsically Islamic fostered the magus while Christendom preferred the wise judge.

Solomon belongs to the three monotheisms of the Middle East, appears in the Bible and the Koran, and in Judaic folklore and Kabbalistic belief. The wise king cuts a majestic yet enigmatic figure, and his deeds and characteristics, as related in the scriptures of three faiths, provide the seedstore from which the fantasies of the Nights have grown so richly. The ‘sagest of all sages, the mage of all mages’, he combines kingship and prophecy with magic, and passes from mainstream religion into mysticism and hermetic lore, with numerous wisdom books from the Bible as well as medieval and later grimoires or magic handbooks claiming his authorship (such as the Clavis Salomonis – The Key of Solomon – and the Ars notoria ); Solomonic wisdom, emerging from the Jewish-Hellenistic culture of the Middle East in antiquity, enjoyed remarkable longevity, and continued to be collected, copied and revised in manuscripts in various languages well into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Solomon is credited with authorship of the Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, the Book of Wisdom itself, and with the Book of Proverbs, books which include the most intense lyric passages of the Bible as well as the Wisdom tradition of the Middle East; both these strong strands weave through the 1001 Nights, where the stories are cadenced by bursts of ecstatic poetry on the one hand and fabulist exempla on the other. His myth meets and combines with those of others – of the hero-kings and prophets, Alexander the Great, Merlin, Hermes Trismegistus and Virgil.

The jinni Sakhr, shaggy and clawed, emerges from the bottle of the Fisherman, and towers to the sky. H. J. Ford, for Andrew Lang’s retelling, 1898.

There are other figures of great wisdom in holy scripture – the three kings are called ‘the wise men from the east’ in the New Testament, and there are numerous prophets, of course, but Solomon surpasses them all because, when asked in a dream what he most desires, he does not ask for money and power or long life but responds by praying to God for ‘an understanding heart to judge thy people and to know good and evil’ (2 Chronicles 1: 7–12). As a result, God answers his prayer and ‘Solomon’s wisdom excelled the wisdom of all the children of the east country, and all the wisdom of Egypt’ (1 Kings 4: 30). The reference to Egypt, the most fertile and ancient repository of magical wisdom, gives Solomon explicit superiority to that knowledge, as Moses (and Aaron) surpass Pharaoh’s magicians in the Bible. The Middle Eastern scholar Chester Charlton McCown, commenting on Solomon’s character as a magus, writes, ‘Few [traditions] have a richer and more varied documentation than that which glorifies the wisdom of Solomon. It may well serve as an example of the manner in which the human mind works in certain fields.’

In the Bible, Solomon’s wisdom translates into practical knowledge: he is no hermit or meditative philosopher, but pursues the via activa as an astronomer and natural scientist, as well as a judicious ruler handing out his celebrated and cunning decisions. God has given him knowledge of the stars and their relation to time, understanding of the properties of plants and roots; he can also read thoughts (Book of Wisdom 7: 17–22). The folklore that the king inspires in the Middle East, before Islam was founded, flows into the Arabian Nights. For example, The Testament of Solomon, a splendid phantasmagoria about Solomon drilling demons to build the Temple, is a Greek compendium composed in Jewish circles before AD 300, with some Christian additions and many affinities with later Koranic and Middle Eastern folklore. The New Testament scholar (and ghost story writer) M. R. James commented in 1899, ‘No one has ever paid very much attention to this futile, but exceedingly curious, work . . . related to Greek magical papyri and . . . fairy and demon stories of East and West.’

Since then there has been more interest in this richly imaginative catalogue of demons, which is vividly cast in the first person of Solomon reviewing his life; it recounts a series of conversations between Solomon and the devils, whom he summons by power of his ring and the sign of the pentacle engraved on its gemstone, which has been given to him by the archangel Michael. The devils include some who have since achieved fame, like Beelzebub and Asmodeus, alongside scores of others who have not; they each have different very specific victims and ingenious – diabolical – ways of doing harm. One by one they are conscripted against their will and set to perform tasks that match their spheres of activity: the demoness Onoskelis, who strangles her victims in a noose, is ordered to spin the hemp to make ropes to haul materials. Later in the story, one of the demons whom Solomon tames links interestingly to the Nights: the king’s help is requested in a pitiful letter by the ruler of Arabia, where the people are suffering from a demon wind (‘its blast is harsh and terrible’). Solomon sets the request aside, as he is concentrating on raising the keystone of the Temple, but it is so huge and heavy that more help is needed besides Onoskelis’s rope-making. But later, he dispatches a servant to Arabia with a leather flask and his seal, and tells him to hold it open facing the wind like a windsock and when it has filled out to close the neck with the seal; he is then to bring the devil wind back to Jerusalem.

He does so; and the wind duly dies down, to the relief and gratitude of the Arabs. Three days later, the servant returns to Jerusalem, and the story continues:

‘And on the next day, I King Solomon, went into the Temple of God and sat in deep distress about the stone of the end of the corner. And when I entered the Temple, the flask stood up and walked around some seven steps and then fell on its mouth and did homage to me. And I marvelled that even along with the bottle the demon still had power and could walk about; and I commanded it to stand up.’

This demon tells him his name – Ephippass – and promises to do anything Solomon wishes. The king orders him to lift the keystone into place, which he does, later going on mysteriously to raise a huge column on a pillar of air.

With this miracle, the intermingling of air with spirits takes the form of physical currents – wind, even tornadoes – and the demon announces the feats of sprites like Ariel and the tempest he raises by enchantment. But the ‘Testament’ also provides some of the material that will be worked into the background of the Nights; its marked love of aerodynamic wonders – the flight of the jinn, of Aladdin’s palace and other prodigious displacements and overnight sensations – can be seen taking shape in this storyteller’s fantasy.

‘The Testament of Solomon’ takes the form its title suggests: at the end of his life the wise king is giving an account of himself, so, setting aside its anecdotal supernaturalism, the work makes a real attempt to make sense of Solomon’s complex character as both a godly, wise man of sacred scriptures and an apostate who worships false gods. It does so by concluding with the story from the Bible that he fell in love with the daughter of Pharaoh and ‘many strange women’ besides: ‘And he had seven hundred wives, princesses, and three hundred concubines . . . For it came to pass, when Solomon was old, that his wives turned away his heart after other gods . . .’ (I Kings 14). Among these gods, the Bible mentions Ashtoreth, and Milcom ‘the abomination of the Ammonites’, and how Solomon sacrificed to them. For this reason, the God of the Bible eventually prevents Solomon’s son from inheriting his kingdom.

King Solomon in the Bible is led astray by women: the daughter of Pharaoh urges him to worship her gods (?Antwerp, sixteeenth century).

In relation to the Arabian Nights, this fall from grace gives Solomon an equivocal, even lesser status in the eyes of Western audiences. In the Muslim sacred book, by con...