- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

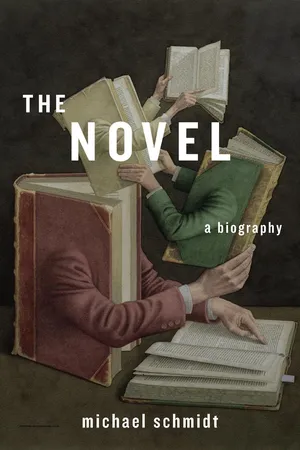

The 700-year history of the novel in English defies straightforward telling. Geographically and culturally boundless, with contributions from Great Britain, Ireland, America, Canada, Australia, India, the Caribbean, and Southern Africa; influenced by great novelists working in other languages; and encompassing a range of genres, the story of the novel in English unfolds like a richly varied landscape that invites exploration rather than a linear journey. In The Novel: A Biography, Michael Schmidt does full justice to its complexity.

Like his hero Ford Madox Ford in The March of Literature, Schmidt chooses as his traveling companions not critics or theorists but "artist practitioners," men and women who feel "hot love" for the books they admire, and fulminate against those they dislike. It is their insights Schmidt cares about. Quoting from the letters, diaries, reviews, and essays of novelists and drawing on their biographies, Schmidt invites us into the creative dialogues between authors and between books, and suggests how these dialogues have shaped the development of the novel in English.

Schmidt believes there is something fundamentally subversive about art: he portrays the novel as a liberalizing force and a revolutionary stimulus. But whatever purpose the novel serves in a given era, a work endures not because of its subject, themes, political stance, or social aims but because of its language, its sheer invention, and its resistance to cliché—some irreducible quality that keeps readers coming back to its pages.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Prologue

- Introduction

- 1. “Literature is Invention”: Mandeville’s Travels, Ranulf Higden’s Polychronicon, De Proprietatibus Rerum

- 2. True Stories: William Caxton, Thomas Malory, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs

- 3. Three Springs: Sir Philip Sidney, Fray Antonio de Guevara, John Lyly, Thomas Nashe

- 4. Before Irony: John Bunyan

- 5. Enter America: Aphra Behn, Zora Neale Hurston

- 6. Impersonation: Daniel Defoe, Truman Capote, J. M. Coetzee

- 7. Proportion: François Rabelais, Sir Thomas Urquhart, Jonathan Swift, Samuel Johnson, Voltaire, Oliver Goldsmith, Alasdair Gray

- 8. Sex and Sensibility: Samuel Richardson, Eliza Haywood, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, John Cleland

- 9. “Nuvvles”: Miguel de Cervantes, Alain-René Lesage, Henry Fielding, Tobias Smollett, Frederick Marryat, Richard Dana, C. S. Forester, Patrick O’Brian

- 10. “A Cock and a Bull”: Laurence Sterne

- 11. The Eerie: Horace Walpole, Clara Reeve, William Beckford, Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Gregory Lewis, Charles Brockden Brown, Charles Robert Maturin

- 12. Listening: Maria Edgeworth, John McGahern, James Hogg, Sir Walter Scott, John Galt, Susan Ferrier

- 13. Manners: Fanny Burney, Jane Austen

- 14. Roman à Thèse: Thomas Love Peacock, William Godwin, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Mary Shelley, Thomas Carlyle

- 15. Declarations of Independence: Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe

- 16. The Fiction Industry: Charles Dickens, Harrison Ainsworth, Elizabeth Gaskell, Wilkie Collins

- 17. Gothic Romance: Charlotte Brontë, Emily Brontë, Anne Brontë

- 18. Real Worlds: Frances Trollope, William Makepeace Thackeray, Anthony Trollope, Benjamin Disraeli

- 19. “Thought-Divers”: Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe

- 20. The Human Comedy: Victor Hugo, Stendhal, Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, Émile Zola

- 21. Imperfection: George Moore, George Eliot, Louisa May Alcott, George Meredith, George Gissing, Samuel Butler, Edmund Gosse

- 22. Braveries: Robert Louis Stevenson, W. H. Hudson, Bruce Chatwin, Richard Jefferies, William Morris, Charles Kingsley, Henry Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling

- 23. Smoke and Mirrors: Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), Rudolf Raspe, Bram Stoker, Ouida, Marie Corelli, Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde, Denton Welch, Arthur Conan Doyle, J. M. Barrie, Max Beerbohm, Kenneth Grahame

- 24. Pessimists: Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad, Stephen Crane

- 25. Living through Ideas: Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy

- 26. The Fate of Form: William Dean Howells, Henry James, Cynthia Ozick, Mrs. Humphry Ward, Edith Wharton, Sinclair Lewis, Marcel Proust, Dorothy Richardson, Anthony Powell, Henry Williamson, C. P. Snow

- 27. Prodigality and Philistinism: Artemus Ward, Mark Twain, George Washington Cable, Theodore Dreiser, Frank Norris, Jack London, Upton Sinclair

- 28. Blurring Form: Willa Cather, Sarah Orne Jewett, Marilynne Robinson, Janet Lewis, Kate Chopin, Sherwood Anderson, Gertrude Stein, Laura Riding, Mary Butts

- 29. Social Concerns: H. G. Wells, Rebecca West, Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, Somerset Maugham, Hugh Walpole, Frederic Raphael, Aldous Huxley, Arthur Koestler, George Orwell

- 30. Portraits and Caricatures of the Artist: James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, Samuel Beckett, G. K. Chesterton, Anthony Burgess, Russell Hoban, Flann O’Brien, Donald Barthelme

- 31. Tone and Register: Virginia Woolf, E. M. Forster, Paul Scott, J. G. Farrell, Norman Douglas, Ronald Firbank, Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, Kazuo Ishiguro, Elizabeth Bowen, Edna O’Brien, Jeanette Winterson

- 32. Teller and Tale: D. H. Lawrence, John Cowper Powys, T. F. Powys, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Durrell, Richard Aldington, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac

- 33. Truth to the Impression: Ford Madox Ford, Ernest Hemingway, Jean Rhys, Djuna Barnes, John Updike, Don DeLillo, Joyce Carol Oates, Anne Tyler, Julian Barnes

- 34. Elegy: Thornton Wilder, William Faulkner, Ellen Glasgow, Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, Harper Lee, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, Thomas Wolfe, Malcolm Lowry, Joyce Cary

- 35. Essaying: Edmund Wilson, Gore Vidal, John Dos Passos, E. E. Cummings, Mary McCarthy, Katherine Anne Porter, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Steinbeck, John O’Hara, Nathanael West, William Gaddis, David Foster Wallace

- 36. Enchantment and Disenchantment: Vladimir Nabokov, Ayn Rand, Radclyffe Hall, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Elizabeth Taylor, Muriel Spark, Gabriel Josipovici, Christine Brooke-Rose, B. S. Johnson, William Gass, John Barth, Harry Mathews, Walter Abish, Thomas Pynchon, Jonathan Franzen

- 37. Genre: Daphne du Maurier, Barbara Cartland, Catherine Cookson, et al.; Bret Harte, Zane Grey, et al.; Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Elmore Leonard, Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, et al.; H. P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, et al.; Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, Ursula Le Guin, et al.

- 38. Convention and Invention: David Garnett, J. B. Priestley, L. P. Hartley, Richard Hughes, Storm Jameson, Walter Greenwood, H. E. Bates, Ethel Mannin, Olivia Manning, Stella Gibbons, V. S. Pritchett, Robert Graves, Doris Lessing, Angela Carter, Elaine Feinstein, Colm Tóibín, Alan Hollinghurst

- 39. Propaganda: Christopher Isherwood, Edward Upward, Paul Bowles, Jane Bowles, Edmund White, Henry Green, Evelyn Waugh, William Boyd, Graham Greene, R. K. Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, Rohinton Mistry, V. S. Naipaul, Caryl Phillips, Timothy Mo

- 40. The Blues: Richard Wright, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, William Styron

- 41. Displacement and Expropriation: Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong’o, George Lamming, Wilson Harris, Ben Okri, Wole Soyinka, Nadine Gordimer, Olive Schreiner, Bessie Head, Alice Walker

- 42. Making Space: Henry Handel Richardson, Patrick White, David Malouf, Peter Carey, Christina Stead, Robertson Davies, Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Maurice Shadbolt, Janet Frame, Keri Hulme, Anita Desai, Salman Rushdie, Earl Lovelace

- 43. Win, Place, and Show: William Golding, Angus Wilson, Margaret Drabble, Malcolm Bradbury, David Lodge, Iris Murdoch, A. S. Byatt, Hilary Mantel, John Braine, Alan Sillitoe, Kingsley Amis, John Fowles, Ian McEwan, Peter Ackroyd, Graham Swift, J. G. Ballard

- 44. Truths in Fiction, the Metamorphosis of Journalism: E. L. Doctorow, John Gardner, Norman Mailer, Kurt Vonnegut, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Joseph Heller, Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Cormac McCarthy, Michael Chabon, Richard Ford, Bret Easton Ellis

- 45. Pariahs: Franz Kafka, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, Mordecai Richler, J. D. Salinger, Philip Roth, Jeffrey Eugenides, Paul Auster, Martin Amis

- Timeline

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app