![]()

PART ONE

Inside the Empire

![]()

1

Entering the Order

Plague swept across Portugal in the year of André Palmeiro’s birth. The outbreak not only devastated the capital, it laid low cities and towns throughout the kingdom. Such was the ferocity of this epidemic that it became known to posterity as the peste grande. Rumors of disease began to spread about the capital city in June 1569, shortly after the first telltale growths were spotted on the dying.1 The contagion spread rapidly in Lisbon, one of the largest cities in sixteenth-century Europe. Its roughly ninety thousand inhabitants lived in densely packed neighborhoods that sprawled over the hills on the northern bank of the Tagus River.2 Contemporaries blamed the continual traffic of ships from around Europe and beyond for the outbreak but, whatever its cause, by midsummer there was no stopping its spread. According to one chronicler, between fifty and sixty people died every day in the capital in late June, and thousands fled in fear of a cataclysm predicted for the new moon of July 10. Before that fated night, “the city was emptied out in such a crazy rush, without order or direction, each one heading off without knowing where, going to the suburbs with women, children, and goods to huddle under the olive trees.” Afterward, those who could proceeded beyond the city’s outskirts while the poor, lacking alternatives, returned to weather the crisis.3 Death was everywhere, but the infant André, who had been born to Salvadora Fernandes and António Palmeiro in Lisbon during the first days of 1569, was spared.4

Nothing else is known about the circumstances of Palmeiro’s birth or infancy, and little information survives about his youth. No personal writings describe his formative years, and the available sources are laconic. What data are available were set down perfunctorily when he joined the Jesuits in 1584. As was customary for those who entered religious life in the early modern period, postulant Palmeiro made vows in which he identified himself. His name, his parents’ names, and his age were recorded, but that is all. The Society of Jesus did not require any more in writing about his parents, their professions, or their social status. The dates of their deaths are not recorded, and Palmeiro does not mention them in his later correspondence. The only reference to any aspect of his parents’ presence in his life is a brief note that Palmeiro’s mother was still in Lisbon in 1617, the year he sailed to India.5

It is fitting that the man who would become such a loyal servant of the Society of Jesus should only begin to appear in the historical record after entering its ranks. From the order’s perspective, his life changed completely when he took religion. For his brethren, Palmeiro’s life in the secular world was of little interest; it was as if his true date of birth was the moment in 1584 when he joined their number. But in an age when signs and omens enjoyed widespread currency, they did record a story about the presage of piety that young André showed while he was a student at the Jesuit Colégio de Santo Antão in Lisbon.6 Based on this reference—the only one identified for this study—it is possible to reconstruct the general pattern of his primary education and give some idea of the context in which he spent his youth. There are more frequent references to Palmeiro’s training at the Jesuit college in Coimbra, as well as to his early career as a member of the Society in that city. Yet, despite their greater number, those archival traces are rudimentary; they are brief entries in personnel catalogues, the lists that served to record biographical information about all Jesuits in the order’s provinces.

While Palmeiro gradually moves from obscurity to clarity in the historical record during the period from his birth until his ordination as a priest at century’s end, little can be said about his individual experience. It is therefore necessary to focus on the institutions and communities that gave him an intimate knowledge of Jesuit patterns of life in late sixteenth-century Portugal. This awareness of how the order functioned in Europe would be the most valuable baggage that he would carry with him to Maritime Asia. Palmeiro garnered this experience over the many years that he spent as a student, novice, and instructor in the Society’s colleges, and it was the yardstick that he would use to measure Jesuit life in the colleges and missions overseas.

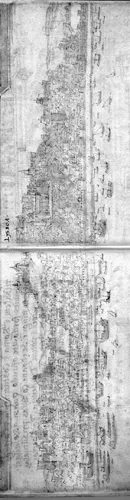

The Colégio de Santo Antão was the Jesuits’ main educational establishment in Lisbon in the early modern period. It stood just beyond the northern edge of the city’s late medieval walls, just below the Castelo de São Jorge, in the newer districts that accommodated the capital’s swelling population. The college opened in 1552, a decade after the first Jesuits arrived in Portugal, offering a curriculum of Latin grammar and rhetoric to boys and young men.7 By the mid-1570s, when Palmeiro was a student, it provided nine levels of instruction in Latin and two in moral theology. Most of the Latin students were boys who ranged from seven to sixteen years of age. They were divided among classes in grammar and in the “humanities”—that is, Latin and Greek poetry and prose as well as rhetoric. The students of moral theology or, more specifically, casuistry were seminarians, parish priests, or members of other religious orders. According to reports from Palmeiro’s time at Santo Antão, the students numbered from 1,300 to 1,500. These enrollments were so great that the Society purchased a nearby site for a more spacious college in the 1580s. As was customary in the Society’s schools, education was provided tuition-free by the college’s community of roughly sixty Jesuits, approximately fifteen of whom were priests and the rest brothers.8

Palmeiro would have followed the standard educational cursus at this Lisbon college in the late 1570s and early 1580s. Although the curriculum taught in the Society’s schools evolved until 1599, when the final version of the Ratio Studiorum (Plan of Studies) imposed uniformity on Jesuit teaching, its general contours were established by the time he began his studies.9 The youngest students at Santo Antão would first learn reading, writing, and religion in their native tongue. The transition to Latin was made gradually over the first three years. Afterward students were expected to compose texts and speeches in Latin, and to speak that language while at school. According to a mid-sixteenth-century Jesuit teaching guide, those who showed skill in composition were invited to perform public recitations. By the fourth or fifth years of the curriculum, students began to study the works of Roman authors, especially Cicero and Virgil. The final years of the program, when the students had reached adolescence, were devoted to rhetoric as well as to introductory Greek.10 This last curricular stage consisted of repeated compositions, recitations, and examinations aimed at conferring eloquence in speech and writing.

FIGURE 1.1. View of Lisbon, seen from the Tagus River, drawn in 1571 by Francisco de Holanda. The first Jesuit Colégio de Santo Antão was situated on the slope of the castle hill, behind the great Rossio Square at the center of the left side. The Society’s Professed House of São Roque was located on the crest of the hill opposite the castle at the far left.

Although the educational program at Santo Antão relied primarily on classical authors, Jesuit education was imbued with the spiritual charge of the Catholic Reformation. Students were obliged to attend doctrine classes and masses, and were assigned devotional topics for their compositions in poetry and prose. Membership in honorary clubs required students to participate in religious brotherhoods and assist at rituals such as the singing of the litanies. The student plays that were staged during the academic year typically had doctrinal or devotional content. For instance, in 1579, when Palmeiro would have been in the middle of his Latin studies, a “tragicomedy of the story of Jonah” was prepared by the college’s oldest students.11 The spiritual side of Jesuit education apparently appealed to him. While it is not known if Palmeiro participated in student devotions or theater, it is certain that he spent much time in the college chapel. Recalling fond memories from his youth as he lay dying on the far side of the world six decades later, he mentioned how he had eagerly helped the sacristan with duties such as placing the altar cloths.12

Palmeiro’s time at Santo Antão was nevertheless not without incident. The late 1570s and early 1580s were a time of upheaval in Lisbon, and the college’s community suffered with the general population. Famine came in 1578, appearing at almost the same moment that King Sebastian I (r. 1557–1578) decided to pursue his ill-advised Moroccan expedition. And the city once again suffered an epidemic: Palmeiro saw his studies interrupted in the late spring of 1579 when contagion forced the closing of Santo Antão. The annual report sent from the Portuguese Jesuits to their brethren in Rome painted a lamentable scene of that year’s events. Sickness reigned over the kingdom for more than a year: First spread a catarrh, “which spared no one and could quickly ravage an entire college.” Then came an outbreak of plague, which “raged furiously for the entire year, causing great damage throughout the city with the death of more than fifty thousand people.” By the time the danger had passed and the schools could open once again, “the city was so devastated by the past troubles that very few students attended.”13

Following upon famine, pestilence, and death, war came to Lisbon while Palmeiro was a student. The succession crisis that began in August 1578 at the Battle of Alcazarquivir would end in the summer of 1580 with the invasion of Portugal by Castilian armies. The dynastic transition culminated in the summer of the following year, when Don Felipe II of Castile arrived to be acclaimed as Dom Filipe I of Portugal (r. 1580–1598). Palmeiro thus lived most of his life as a subject of the Habsburg monarchs who reigned over Portugal and its empire from Madrid. What he felt about this is unclear: his voluminous later writings never mention his thoughts on royal affairs. In any case, it would seem that the greatest impact of all these political and social events on the eleven-year old boy was the sporadic interruption of his schooling. The repeated closures of Santo Antão due to disease and war meant that Palmeiro did not finish his study of Latin and “humanities” before he headed to Coimbra to join the Society of Jesus at the customary age. He would therefore have to complete his early education at the same time as his novitiate.

Shortly after his fifteenth birthday, André Palmeiro entered the Society of Jesus. The motives for his decision are not clear. It is not surprising that a young man who had been a student at a Jesuit college would have considered joining the Society. By the time Palmeiro was a student, the Society’s classrooms were the order’s primary recruitment pools. It is likely that he was attracted by the Jesuits’ spirituality, given his desire to frequent Santo Antão’s chapel and in light of the ample proof of his piety from later on. Others may have joined the Society because they were attracted by its academic activities, or by the possibility of social promotion it offered to men of low birth, or even in order to attain stability in an uncertain age, but none of this appears to have driven Palmeiro’s choice—at least to the extent that documents written at the time of his death can be trusted in their suggestion that he was a natural candidate for religious life. It is possible that his instructors encouraged him to join their order, but he may have made the request himself, as other young men did each year, not all of them successfully. For example, in 1578 the Jesuits at Santo Antão claimed that many of their students entered the religious life in other orders, while “the Society accepted three who were chosen from among the others who desired and requested entry.”14

Such confidence about their selectivity should be expected in the annual reports that the Jesuits circulated among their Portuguese residences and then forwarded to the superior general in Rome. These reports were meant to be read aloud at mealtimes and therefore had the specific intent of both informing and edifying their readers (or listeners, as was more often the case). While one should not dismiss the Jesuits’ boast that many sought to join them, it cannot be ignored that in the 1580s the Society was still a new presence in Portugal. Their “institute”—that is, the set of rules that constituted their manner of spiritual and communal life—was a recent addition to the spectrum of religious life. Not two generations had passed in the history of the order in Portugal, whereas three centuries had gone by since the arrival of the Dominicans and the Franciscans. The Augustinians, the Carmelites, and the Trinitarians enjoyed similar pedigrees, while the roots of the Benedictines and Cistercians stretched back to the Reconquista period. The Jesuits were by comparison upstarts in an age that resisted novelty and innovation, especially in matters of religion.

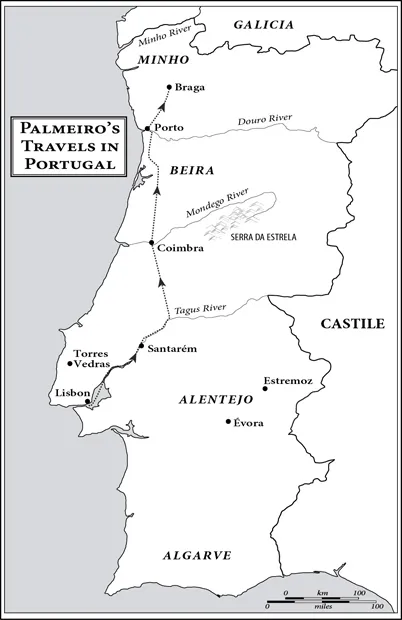

Despite its recent vintage, the Society enjoyed a rapid expansion in Portugal, as it did elsewhere in Europe. By early 1584, when Palmeiro joined the order, its members numbered 504 men distributed among ten residences. The Society’s growth was due, above all, to royal favor. King João III helped the Jesuits acquire residences in Lisbon and Coimbra in the 1540s, and as their order began to focus pastoral energies on education, further endowments helped the Jesuits open colleges throughout the kingdom. The schools in Lisbon, Braga, Porto, and Funchal (on Madeira) offered a curriculum in Latin and Greek grammar and rhetoric in addition to courses in moral theology, while those in Coimbra and Évora presented those same classes as well as others in the higher sciences of philosophy and theology.15 In the 1580s prospective Portuguese Jesuits were required to attend one of these last two colleges since they were the only ones that had novitiates. The Colégio de Jesus at Coimbra and the Colégio do Espírito Santo at Évora were thus the Society’s largest communities in Portugal, accounting for over half of the order’s priests and brothers. In Coimbra, Palmeiro joined the biggest of them all, where he was one of 178 Jesuits, 139 of them brothers like him.16

Jesuit sources indicate that Palmeiro made his first novice vows on January 14, 1584. Although the register he signed on that occasion seems not to have survived, a similar bo...