Most scholars in the field of communication research may find it slightly odd to imagine a counterfactual history of research practice. After six decades of conducting surveys and experiments and accumulating findings within an intuitively satisfying paradigm of research practice (Neuman and Guggenheim 2011) there is a certain taken-for-grantedness about how things are done. But, briefly, let us review some arguably quite reasonable alternatives.

The first alternative has already been introduced in the prologue (and will turn up from time to time as a continuing historical trope in this book). Not only could it have been otherwise; communication scholarship could have been built on the polar opposite intellectual starting point. Consider the historical roots of sociology in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Instead of a concern with an overly strong central control via mass media propaganda the central concern of early sociology was a lack of a social glue, a meaningful basis for social organization and coordination that would survive the uprooting transition from smaller rural communities where people knew each other to the anomic crowds of industrialized urban centers (Merton 1968; Coser 1971; Giddens 1976; Jones 1983; Collins 1986). Had the field of communication scholarship started to develop its disciplinary identity fifty years earlier, this might well have been the case. Or communication scholarship, like the beginnings of political science, could have focused not on the psychology of persuasion but on aggregate structures such as communication systems within communities and nation-states. Political science as the comparative study of constitutions and legal systems persisted a half century up to the “behavioral revolution” in the field in the 1950s (Crick 1959). Or the systematic study of mediated communication could have evolved from literary and cultural studies focusing on the text, narrative structure, and cultural resonances of the mass media. That did happen, of course, with abounding energy about twenty-five years later, but it evolved as a counterpoint to experiments and surveys rather than a precursor and this counterpoint continues to represent an intellectual fault line in the field (Grossberg 2010). Or one could imagine the study of the media as evolving as a practical and applied field perhaps more akin to the curriculum and culture of schools of journalism or cinema or departments of advertising or public relations. Such departments and schools exist, but almost always at arm’s length from academic communication studies. Also one could imagine an experimentally oriented field of scholarship focused on learning from the media rather than persuasion as the research paradigm currently characteristic of educational psychology, educational technology, and some branches of information science (Chaffee and Berger 1987). Finally, the fields of mediated communication and interpersonal communication scholarship could have shared common intellectual roots. Some may argue that they do, but since the publication of Miller and Steinberg (1975) it is generally acknowledged that these scholarly traditions have largely gone their separate ways.

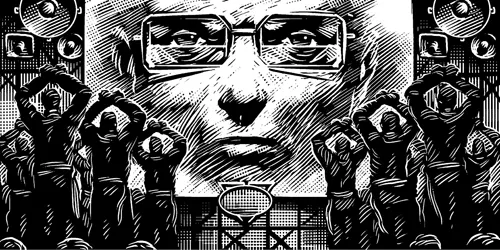

Hypodermic Effects

Perhaps the iconic image of the pivotal midcentury period is the dominating and demanding face of Big Brother from George Orwell’s 1984. Orwell’s book was titled with a year in the near future, but the manuscript was written just after the Second World War and published originally in June of 1949. The novel’s central thematic of totalitarian propaganda and mind control was an artful mix of not-so-subtle references to both Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Russia. Orwell’s protagonist, Winston Smith, is a lowly government bureaucrat working at the Ministry of Truth as an editor, and his primary responsibility is changing the official (in fact, the only) historical record so that the official past corresponds to the needs of the current central authority. He routinely rewrites the records and alters photographs so that those individuals now out of favor become “unpersons” and inconvenient historical documents are irretrievable deleted down the memory hole.

A particularly telling sequence early in the book is the required daily routine of the “two-minutes hate”:

It was nearly eleven hundred, and in the RECORDS DEPARTMENT, they were dragging the chairs out of the cubicles and grouping them in the centre of the hall opposite the big telescreen, in preparation for the Two Minutes Hate.… The next moment a hideous, grinding speech, as of some monstrous machine running without oil, burst from the big telescreen at the end of the room. It was a noise that set one’s teeth on edge and bristled the hair at the back of one’s neck. The Hate had started.

As usual, the face of Emmanuel Goldstein, the Enemy of the People, had flashed on to the screen. There were hisses here and there among the audience. Goldstein was the renegade and backslider who once, long ago (how long ago nobody quite remembered), had been one of the leading figures of the Party, almost on a level with BIG BROTHER himself, and then had engaged in counter-revolutionary activities, had been condemned to death and had mysteriously escaped and disappeared.… Goldstein was delivering his usual venomous attack upon the doctrines of the Party—an attack so exaggerated and perverse that a child should have been able to see through it, and yet just plausible enough to fill one with an alarmed feeling that other people, less level-headed than oneself, might be taken in by it.…

But what was strange was that although Goldstein was hated and despised by everybody, although every day and a thousand times a day, on platforms, on the telescreen, in newspapers, in books, his theories were refuted, smashed, ridiculed, held up to the general gaze for the pitiful rubbish that they were—in spite of all this, his influence never seemed to grow less. Always there were fresh dupes waiting to be seduced by him. A day never passed when spies and saboteurs acting under his directions were not unmasked by the Thought Police. He was the commander of a vast shadowy army, an underground network of conspirators dedicated to the overthrow of the state.…

In its second minute the Hate rose to a frenzy. People were leaping up and down in their places and shouting at the tops of their voices in an effort to drown the maddening bleating voice that came from the screen. The little sandy-haired woman had turned bright pink, and her mouth was opening and shutting like that of a landed fish.…

The Hate rose to its climax. The voice of Goldstein had become an actual sheep’s bleat, and for an instant the face changed into that of a sheep. Then the sheep-face melted into the figure of a Eurasian soldier who seemed to be advancing, huge and terrible, his sub-machine gun roaring, and seeming to spring out of the surface of the screen. But in the same moment, drawing a deep sign of relief from everybody, the hostile figure melted into the face of BIG BROTHER.

Orwell’s scenario mixes the anti-Semitic racial propaganda of Nazi Germany and Stalin’s vilification of Trotsky (the Goldstein character) as a bête noire and traitor to the cause. Even our protagonist, the reluctant Winston Smith, finds himself caught up in the frenzy of the moment. It may represent rather starkly wrought dramaturgy, but it powerfully captures the concerns of the era about the atomized individual, mass society, the lonely crowd, the individual helpless against the onslaught of psychologically sophisticated propaganda. The extreme case of propaganda, of course, is systematic mind control or “brainwashing” that occupies a special place in the novel’s conclusion as Smith’s fears and weaknesses are exploited to break down his will to resist.

We continue to use the terms Orwellian, big brother, and thought police in common parlance today to conjure up these enduring themes. In the decades following its publication 1984 would sell tens of millions of copies and be translated into more than sixty different languages, at that time the greatest number for any novel (Rodden 1989). The hot war had been won, but the cold war of competing ideologies was just beginning. Orwell’s novel represents a synecdoche for the very real and not entirely unreasonable dominating mood of fear and concern in the West following the war. It was not just a backward-looking retrospective on the theories and practices of Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels (Baird 1975; Herzstein 1978) but a commanding fear that if it could happen in Europe it could happen again there or in the United States or in response to communist propaganda in the developing world. In the early 1950s the fear of communism was briefly but dramatically manipulated by the junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, with the ironic result that his success in capturing the media spotlight with trumped-up images of a state department overrun with Soviet agents reinforced fears about the threat of propaganda and demagogic manipulation of public opinion, not just from the Left but from the Right, as well (Rogin 1967; Bayley 1981; Hamilton 1982; Gibson 1988; Gary 1996). The war in Korea generated new images of the extreme form of manipulation—Chinese thought reform and brainwashing (Lifton 1961). Richard Condon’s 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate and the equally influential 1962 MGM movie version describing former army officers secretly brainwashed in China as sleeper agents to assassinate politicians and take control of the government resonated powerfully with the public mood.

Vance Packard’s presumptively nonfiction expose of commercial subliminal persuasion in the Hidden Persuaders, published in 1957, warned that imperceptibly brief flashed images of Coca-Cola on a motion picture screen generated sudden and inexplicable thirst among audience members who thronged to the concession stand for an extralarge drink. (Actually the study was a fake, created as a publicity stunt; see Pratkanis 1992.) It initiated a tradition of critical scholarship on manipulative commercial and political advertising still active today (Key 1974; Baker 1994; Goldstein and Ridout 1994; Turow 1997; Chomsky 2004).

We review these prominent themes from the popular and political culture of the midcentury because they are central to the discussion of the propaganda problem. As noted at the conclusion of the prologue, systematic communication research and the institutionalization of departments of communication in the academy began not as virtually all of the other social science disciplines did at the end of the nineteenth century but rather at the middle of the twentieth. Coming to a disciplinary identity at the conclusion of the Second World War, the field of communication research adopted a paradigm designed to address the propaganda problem, the concern about the hypodermic injection of manipulative im...