![]()

CHAPTER 1

From Toronto Blessing to Global Awakening

Healing and the Spread of Pentecostal-Charismatic Networks

On January 20, 1994, Randy Clark, the pastor of a Vineyard church in St. Louis, Missouri, traveled to Toronto, Ontario, at the invitation of John Arnott, the pastor of the Toronto Airport Vineyard Church, to preach four services. What happened surprised everyone, not least Clark and Arnott. About 160 people attended the first service. When Clark said, “Come Holy Spirit,” people shook, fell down, produced deep belly laughs, felt peaceful, or acted intoxicated. Some converted to Christianity, testified to physical and emotional healing and deliverance from demons, or dedicated their lives as missionaries to bringing good news to the nations of the world. Most controversial were a few people who made loud, animal-like noises such as the roar of a lion. The participants in the Toronto meetings interpreted this unusual behavior as indicating that the Holy Spirit had accepted the invitation to come.1

As news of this revival spread, people came from all over North America and eventually from every continent, representing many racial and ethnic groups, searching for physical and emotional healing or spiritual renewal. Arnott extended the plan for nightly services indefinitely, persuading Clark to stay for forty-two of the first sixty meetings; many other visiting church leaders also took turns preaching. For the first several months, reports of healing in the Toronto meetings were scattered, but over time the frequency of healing claims increased. Services continued six evenings a week—often for six or more hours per night—until 2006, making what was dubbed the “Toronto Blessing” the longest revival meeting in North American history. Indeed, it may be that even as of 2011, the Toronto revivals have not so much waned as decentralized, becoming a less significant pilgrimage destination as its influences have become globally diffused. The Toronto meetings drew an estimated 3 million people, including Catholics, Orthodox, and every Protestant denomination. Approximately fifty-five thousand churches around the world were affected in just the first year as visitors returned home to their own congregations and avowedly brought the “revival fires” with them. Churches all over the world began to report phenomena similar to those occurring in Toronto shortly after a pastor or a few lay members returned from a pilgrimage.2

Not every Christian observer—let alone the secular press—concluded that the presence of the Holy Spirit explained the Toronto Blessing. Within weeks, critics questioned whether the Toronto Blessing was a genuine revival that produced the fruit of conversions to Christianity, increased holiness in the lives of Christians, and outreach beyond the church in missionary evangelism and social benevolence. Some suggested that runaway emotionalism, hypnotic suggestion, pseudo-miraculous psychosomatic healings, or demonically inspired witchcraft constituted more plausible explanations. In his book Counterfeit Revival (1997), the popular evangelical author and radio personality Hank Hanegraaff interpreted Toronto as the epitome of a false revival. Even John Wimber, founder of the Vineyard movement, and the entire twenty-member oversight board of the Association of Vineyard Churches were so disturbed—especially by reports of “exotic” and “extra-biblical” animal noises—that they “disengaged” the Toronto church in December 1995. Shortly before taking this disciplinary action, Wimber had written an endorsement for John Arnott’s book The Father’s Blessing (1995), which justified the avowedly rare animal sounds as prophetic expressions; later, Wimber denied having read that part of the book.3

The Toronto Blessing and the Vineyard movement split their paths. The Toronto Airport Vineyard (TAV) Church was renamed the Toronto Airport Christian Fellowship (TACF). Clark himself was able to keep his St. Louis church and its new missions arm, Global Awakening, in the Vineyard movement. Wimber even encouraged Clark to develop an international healing ministry. Reflecting on his eventual distancing from the Vineyard in a 2005 interview, Clark said that at first he had hoped that Global Awakening could function like one of the Catholic orders, such as the Benedictines, in pushing the Vineyard toward recapturing the movement’s original vibrancy. Clark was disappointed when Wimber seemingly rejected his efforts at revitalization—although Clark also claims that Wimber, near the end of his life (he died in 1997), expressed regret at his decision to disfellowship TAV.4

One of the Toronto Blessing’s severest critics, the Reverend Canon Martyn Percy, a professor of theological education at King’s College London, characterized the Toronto Blessing as theologically “dubious” and “offensive.” Percy was particularly troubled because those who claimed that the Holy Spirit had descended on Toronto seemed to assume that God would “indulge a small, Caucasian-based, international and mainly middle-class group with great blessings, whilst leaving the lot of the poor largely untouched.” Percy concluded in 1998 that there was “just no evidence of that event signifying a global revival.” From the historical vantage of thirteen years since Percy’s assessment, this chapter argues that the Toronto Blessing has significantly influenced the spread of global Christianity—including in the two-thirds world—by increasing the prevalence of prayer for healing and multiplying the number and influence of divine healing claims.5

Toronto-Blessing Pentecostals as a Case Study of Healing Prayer

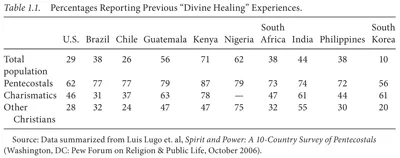

The frequency with which Pentecostals and Charismatics claim healing through prayer distinguishes these groups from other Christians. This may be a surprising claim to those who associate pentecostalism with such practices as speaking in tongues; snake handling; or boisterous, televised appeals for “seed-faith” giving as the ticket to financial prosperity. A 2006 study found that 62 percent of U.S. Pentecostals—compared with 29 percent of the total population—claimed to have “experienced or witnessed a divine healing of an illness or injury.” The same study, conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, surveyed not only the United States but also nine other countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia (table 1.1). The study found sizable percentages of the general population, and even higher percentages of Pentecostals and Charismatics, claiming to have had personal divine healing experiences. Pentecostals are not the only people who pray for healing, but if the goal is to study claims of healing through prayer, pentecostalism is a good place to begin.6

The concept of prayer, even if restricted to Christian prayer, encompasses a wide variety of practices. For example, prayer may be liturgical, conversational, meditative, or petitionary. Pentecostals (like other Christians) may spend time quietly “soaking” in God’s presence or contemplating Bible verses or may combine prayers of adoration and thanksgiving with petitions on the worshiper’s own behalf, intercession for other people, and even commands issued to physical conditions or spiritual entities. A basic theological premise held by many pentecostals is that a personal God responds to prayers in the name of Jesus by the power of the Holy Spirit—although certain individuals and ways of praying are widely considered more effective than others (varying, for instance, by degrees of “faith,” or expectancy). This and subsequent chapters will flesh out this broad-stroke overview through specific examples of how pentecostals may articulate prayers for healing in particular situations.7

When pentecostals pray for divine healing, they often have in mind both a physical cure from disease or disability and a more holistic healing process that produces a sense of emotional and spiritual wholeness. Modern pentecostals are not unique in envisioning healing as benefiting body, mind, and spirit—concerns that are shared by nonpentecostal Christians as well as by participants in holistic healing movements rooted in other religious traditions. Yet many pentecostals do distinguish divine healing from a recovery expected through the regular operation of natural processes. The healing may not be instantaneous or spectacular or appear to violate natural laws—and thus be classified as a miracle. However, divine healing is often understood to proceed more rapidly than usual (as when a tumor dissolves in ten minutes) or under circumstances in which healing would not otherwise be expected (for instance, disappearance of cancer that has already metastasized). In practice, the distinction between divine and natural healing can easily blur. Pentecostals may pray for God to guide the hands of surgeons, make medicines efficacious, or work through psychological counseling, and then credit God for any healing achieved. In the pentecostal worldview, God, as well as angels and demons, may intervene in the natural world by working against—or through—biomedical or psychosomatic processes. The same healing, depending on whether interpreted through a worldview constructed by pentecostals or scientific naturalists, may appear to reflect divine or natural activity.8

The pentecostal networks that emerged from Toronto provide an apt case study for exploring larger questions about healing prayer. As healing became an increasingly prominent theme of the Toronto Blessing, the movement touched off a chain of events that made expectant prayer for healing more common in many Christian churches worldwide. A renewed emphasis on healing prayer—coupled with the widespread perception that such prayers result in divine healing—has contributed to the global spread of Christianity. This is not to say that the Toronto revivals are sui generis, or even that they are the most influential stream of pentecostal Christianity. Yet prayer for healing—accompanied by an expectation that prayer should and often does produce observable results (even if such results are perceived to be more common in the global South)—is a notable feature of Toronto-influenced pentecostalism. Moreover, the fact that healing prayer is practiced in the context of globalized relational and institutional networks facilitates study through the collection of before-and-after medical records, the implementation of survey and clinical research, and long-term follow-up with individuals reporting healing or indirectly affected by healing practices.

I focused my empirical research on two groups, first the Apostolic Network of Global Awakening, headquartered in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania but active in thirty-six countries (most often Brazil), and directed by Randy Clark, a U.S. citizen. The second group is Iris Ministries (IM), which has its headquarters in Pemba, Cabo Delgado, Mozambique, with branches in twenty-five countries; it is directed by Rolland and Heidi Baker, expatriate U.S. citizens naturalized as Mozambicans. Both organizations grew out of Toronto and belong to the same overlapping, globally diffuse pentecostal networks. Randy Clark (born in 1952) and Heidi Baker (born in 1959), who is more of a public figure than is Rolland Baker, are dynamic leaders who are respected and emulated by members of their own networks and more broadly by many pentecostals and other Christians around the world. Clark and Heidi Baker each spend approximately half the year traveling to pentecostal conferences in other states, provinces, and countries. Both of their organizations place great emphasis on prayer for divine healing in day-to-day operations and articulations of vision. Both Clark and the Bakers point to dramatic healing experiences in their own lives that motivate their unconventional lifestyles.9

This chapter sets the stage for the empirical perspectives on healing prayer that are explored in the rest of this book. The narrative begins by contextualizing Toronto-influenced pentecostal prayer within a longer history of Christian prayer for healing and the emergence of global pentecostalism. The Toronto meetings did not occur in a vacuum but grew out of a dense network of institutional and relational connections. The Toronto revivals produced a thickening of those network connections, notably through Clark’s founding of the Apostolic Network of Global Awakening (hereafter abbreviated as ANGA when referencing the larger-than-organizational network, and as GA when referring to Clark’s own ministry entity). This chapter argues that ANGA-bridged networks—though not coterminous with global pentecostalism—exemplify the multidirectional, global patterns of cultural exchange through which healing prayer feeds pentecostal growth. Participation in network activities, notably conferences and international ministry trips, builds a sense of global community. North American ANGA affiliates borrow from pentecostals in countries they visit (such as Brazil, Mozambique, and India) heightened expectation of divine intervention in the natural world, particularly through healing. By emphasizing the capacity of ordinary Christians to become agents of healing, North American pentecostals facilitate the democratization of global healing practices. The interplay of supernaturalism and democratization accentuates the prominence of healing prayer in ANGA-brokered networks, fanning the revivalist expansion of Christianity set ablaze by the Toronto Blessing.

Prayer for Healing in the Context of Global Pentecostal Networks

Prayer for healing is not unique to pentecostalism or even to Christianity. Because sickness and death are universal human experiences, it is not surprising that many of the world’s religious traditions appeal to suprahuman sources of healing energy. Extra-empirical understandings of “energy” are central to healing practices such as acupuncture, tai chi, yoga, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch that draw on traditions that include Taoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Although there are many revealing parallels between pentecostal love energy and other models of energetic healing, the important project of comparison has been reserved for a subsequent book (now in progress).10

The present volume lays the foundation for future comparative work through an in-depth consideration of Christianity, which has aptly been characterized as a “religion of healing.” The religion’s founder, Jesus of Nazareth, reputedly exercised an extraordinary capacity to heal—often by “laying his hands” on the sick—and he commissioned his followers to heal likewise. New Testament instructions for church practice advise that if anyone is sick, “let them call the elders of the church to pray over them and anoint them with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer offered in faith will make the sick person well” (James 5:14–15). Historical records indicate that prayer for healing was a common feature of church practice for at least several hundred years. Over time, the emphasis on healing prayer diminished for a variety of reasons, including a theological refashioning of sickness as an aid to holiness, but the practice of praying for healing never disappeared completely. At the time of the Reformation, during the sixteenth century, the Catholic Church continued to practice healing prayer, whereas the emerging Protestant movement took a more skeptical stance toward the availability of divine healing in the postbiblical era.11

Scattered reports of healing through prayer can be found throughout church history. The number and geographic reach of publicized healings increased greatly in the modern era. The dissemination of newspapers and improved travel technologies made it more likely that activities in one locality would influence events at the opposite end of the globe. News of healings circulated during the Great Awakenings, the transatlantic religious revivals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. John Wesley, the English leader of the eighteenth-century Methodist revivals, recorded numerous instances of healing in response to prayer, most famously the healing of his horse. The best-known evangelist of the First Great Awakening, England’s George Whitefield, claimed that he himself, after prayer, arose from his deathbed to preach the gospel. Charles Grandison Finney, the foremost revivalist of the Second Great Awakening in the antebellum United States, encouraged his congregations to pray expectantly for healing. Contemporaneous with Finney, Edward Irving of the National Scottish Church proclaimed the renewal of healing gifts to audiences numbering over ten thousand. Johann Christoph Blumhardt in Germany and Dorothea Trudel and Otto Stockmayer in Switzerland attracted international attention in the 1840s and 1850s when each of them established “healing homes,” residences where the sick could stay and receive prayer over an extended period of time; newspapers and books carried reports of miraculous cures throughout Europe and around the world. Numerous international visitors traveled to the European healing homes ...