![]()

I

THE RISE OF A CONSTITUTIONAL MODEL OF JUSTICE, 1839–1920

![]()

1

MUSTAFA ALI

Ottoman Justice and Bureaucratic Reform

Mustafa Ali of Gallipoli was a curmudgeonly old man. Disappointed, but not yet defeated by life, he boarded a ship in July 1599 to cross the Mediterranean from Istanbul to Egypt. His career had begun so brilliantly back home in Gallipoli, a small seaside town on the European side of the Dardanelles. As a young poet and star student from a family of religious scholars, he had won entrance at age fifteen to an imperial school in the Ottoman capital of Istanbul. Those were the glorious days of Sultan Suleyman the Lawgiver (1520–1566).

Now past his prime, at age fifty-eight, Mustafa Ali was about to take up the latest in a string of midlevel posts in the Ottoman financial administration. These duties had led him across the empire, to Damascus, Aleppo, Baghdad, Anatolia, Bosnia, and Istanbul. Now he had accepted the post of governor of Jeddah, the important Arabian port. But as his ship crossed the sea, Mustafa Ali still harbored ambition for the office that he had long coveted: governor of Egypt. To remind Sultan Mehmed III (1595–1603) of his talents, he planned to stop for a few months in Cairo and write a report on the state of the province.

Some of Mustafa Ali’s peers ridiculed him for his self-promotion, flowery writing, and tendency to inflate personal disappointment into apocalyptic warnings of Ottoman decline. He compared himself to a phoenix rising above “the shackles of the Chancellery.”1 To modern readers, Mustafa Ali resembles the pompous courtier Polonius in Hamlet, penned by a greater bard of the same era. He routinely sent poems to sultans to dazzle them with his rhetoric. He also admitted to the bad habit of “revealing others’ faults.”

Mustafa Ali’s self-promotion did not obstruct his sharp social and political perception. His personal sense of injustice, piqued by the advancement of men he considered less skilled and more corrupt, triggered his desire to report on the suffering of the sultan’s poorest subjects.2 His lamentation of imperial injustice would inspire a new literary genre called nasihatnameler, or advice books to princes. This bureaucratic movement for justice used the pen and access to power as its repertoire of action. The bureaucrats framed their mission to restore justice (unsurprisingly) in terms of administrative reform. Their books, passed on to successive generations of bureaucrats, led circuitously and contentiously to the triumphant declaration of imperial reform in the 1839 Rose Garden decree. Called the Tanzimat, the reform program sought to turn subjects of the sultan into Ottoman citizens and so mobilize them to save the empire.

Bureaucrats’ reports were responses to the vast changes in the Ottoman empire in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Economic change came as Western Europeans diverted trade from Asia away from Ottoman land routes to sea routes around Africa, and as their conquistadors opened the Atlantic trade with the Americas. Political and military change came as Peter the Great and Catherine the Great expanded Russia into an empire in repeated wars on Ottoman territory. These changes sparked unrest and revolts around the empire. This pressure from below motivated bureaucrats to write their reports and ultimately to act upon them, culminating in what subjects viewed as an Ottoman bill of rights in 1839.

MUSTAFA ALI’S DESCRIPTION OF CAIRO

To Egyptians, Cairo was the “Mother of the World.” To Ottomans like Mustafa Ali, it was the empire’s second capital. In 1599 it housed more than 200,000 residents, a population exceeded only by Istanbul’s half million. Monumental mosques, imperial villas, and vast markets clustered around the magnificent Nile River. Merchants amassed fortunes by transporting foodstuffs grown in Egypt and luxury goods imported from the East to Istanbul and Europe.3 Mustafa Ali lingered in Cairo, before heading across the Red Sea to Jeddah, not only to write his report, but also to conduct research. He knew Arabic from his youthful religious education and he was completing his magnum opus, a world history called The Essence of History, begun in the year of the Islamic millennium (1591–1592). Cairo’s numerous private libraries and bookshops near the prestigious al-Azhar mosque held knowledge that Ottoman elites thirsted for.4

The city that Mustafa Ali found in 1599, however, was not the same as the one he had visited thirty years before. Local people were less friendly. Food was less abundant, and soldiers were an unruly menace in the streets. Mustafa Ali’s candid observations constitute what historians call the first modern bureaucratic report, written without “zeal and bias” and with “shortness and precision.” The introduction proclaims his mission to rescue not just Egypt, but also the whole empire, from crisis:

I had previously visited the land of Egypt around the year [1568] and become thoroughly acquainted with the prosperity of the country.… But in the course of time the state of the world had changed, the various classes of mankind had become distressed in the matter of livelihood, and peace and order had been chased from the face of the earth. Not only in Egypt, also in other provinces, the means of ease and prosperity had become scarce.5

Mustafa Ali’s Description of Cairo combines his favorite themes of Ottoman glory and imminent decline with practical advice about how to restore just and efficient rule. He divided his report into three parts: the praiseworthy features of Egypt, its blameworthy aspects, and an epilogue on how to reverse the corruption of Ottoman rule. “Egypt is God’s treasure-house on earth” and its people are openhearted, generous, pious, and clean, he notes. But they still suffer from bad traits that predated Ottoman rule: they are “rarely beautiful”; the women are immodest compared to Turkish women and wear gems on their turbans; and the poor and African slaves wear so few clothes they are practically naked. Worse, these poor and uncouth Egyptians have taken jobs in government and the military and so the local regiments have become unruly.

Why had bountiful Egypt sunk so low? Corruption. “The managers of the treasury of Egypt resemble hungry wolves and jackals who have broken into a flock of sheep,” Mustafa Ali explained. The government had ceased to guarantee order and equity: prices are no longer regulated, bribery is the rule, and brokers tyrannize the market. The solution: direct rule from Istanbul. Only the Ottoman dynasty can restore Islamic law and justice. The sultan must appoint only Ottoman Turks—not Egyptians—as governors and soldiers in the province.

Mustafa Ali illustrates his model of just government with praise for former Ottoman governors, like Ibrahim Pasha. Appointed in 1584, he was “dedicated to justice, interested in the study of the past, moderate in his acts and manners” and “a merciful friend of the poor.” His successor, Uveys Pasha, was even greater “in regard to absolute justice, rectitude in the collection of revenues, and in showing consideration for both sides.” With strict honesty he still managed to increase tribute paid to Istanbul. By contrast, Governor Mustafa Pasha mismanaged revenues and ruled through extortion. “Finally, they [Egyptians] could not bear his behavior [any longer],” Mustafa Ali wrote. “When he set out to kill certain beys they had him shot and killed with a rifle.”6

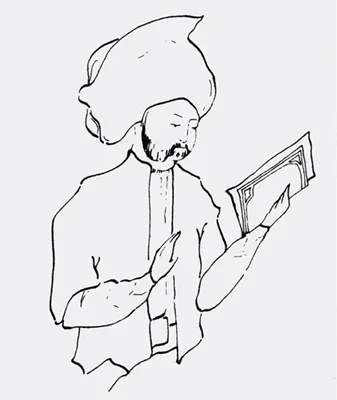

Mustafa Ali of Gallipoli (1541–1600) was a midlevel bureaucrat and historian in the Ottoman empire, who launched a tradition of reform-writing known as the nasihatname. Drawing by Carolyn Brown based on a sixteenth-century miniature.

(From Cornell H. Fleischer, Bureaucrat and Intellectual in the Ottoman Empire. © 1986 Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.)

Just rule, in Mustafa Ali’s view, resembles a circle of interlocking and mutual interests. A prosperous peasantry is the bedrock of good government, because peasants provide tax revenues to support courts and the military. Such a revenue stream is assured only when taxes are legally gathered by honest imperial servants. When the sultan failed to discipline his officers, the “Circle of Justice” broke in Egypt. Despotic governors had siphoned off tribute needed in Istanbul and left troops unpaid. Overtaxed peasants fled from the land. As a result, Mustafa Ali warned, enemies are now poised to grab the Ottomans’ “most essential province.”7

Mustafa Ali closed his report on an optimistic note, assuring Sultan Mehmed III that the flow of truth upward from an honest bureaucrat may yet rescue Egypt from injustice: “Awareness is one of the marks of statesmanship.”8 Mustafa Ali sent off his report and crossed the Red Sea in November 1599. After making a pilgrimage to Mecca, however, he fell ill in Jeddah. Before the sultan could respond to his report, Mustafa Ali passed away in the spring of 1600.

THE OTTOMAN CIRCLE OF JUSTICE

While Mustafa Ali never attained his coveted post in Cairo, his plea for justice reached the highest halls of government. His reports circulated for decades among bureaucrats who shared his anger that honest men were not justly rewarded. They read them not just out of empathy, but also for inspiration. Mustafa Ali became the father of a scholarly movement that elaborated a vision of the just social order as a Circle of Justice.9 If every element of the empire plays its proper role, they believed, then harmony would reign. “Justice,” wrote Mustafa Ali, “means putting things in the places where they belong.”

The Circle of Justice originated among Greek philosophers and was passed on to Ottomans by medieval Persian and Arab scholars. Ottoman bureaucrats adapted it to the structure of their empire by arranging each social estate around the circumference with an assigned function. One version went:

The world is a garden, its walls are the state

The Holy Law orders the state

There is no support for the Holy Law except through royal authority

There can be no royal authority without the military

There can be no military without wealth

The subjects produce the wealth

Justice preserves the subjects’ loyalty to the sovereign

Justice requires harmony in the world.10

This version of the Circle of Justice proclaims Ottoman royal authority as the guarantor of Islamic justice. While earlier Islamic dynasties had ruled solely through Islamic law (sharia), the Ottomans introduced a Central Asian tradition of imperial decree (yasa) to Middle Eastern statecraft. This gave the state greater legislative power and enabled it to regulate a more complex bureaucracy. When Mustafa Ali was young, Suleyman the Lawgiver attempted to align the two legal traditions by codifying imperial law (kanun). He institutionalized legal justice by incorporating a hierarchy of the ulama (Islamic scholars) into the Ottoman bureaucracy.11

The Ottomans’ powerful machinery of rule was viciously depicted by their rivals, the Venetians, as Oriental despotism.12 If despotism is unlimited rule by whim, then the Ottoman sultan was no despot. In the Ottoman view, God had granted the sultan the power to assure the reign of justice on Earth. Divine duty bound the sultan to honor and enforce Islamic law.13 “The sultan is God’s shadow, all oppressed take refuge with him,” Mustafa Ali remarked, quoting the Prophet Muhammad.14

In his major treatise, The Counsel for Sultans, Mustafa Ali used the word justice (adalet) twenty-one times in the preface alone. Its root meaning in Arabic (adadl) is that of equality, balance, and moderation. Its opposite was tyranny (zulm), the extreme imbalance of wealth and power. “To condone the darkness of tyranny is equal to cause the eclipse of the sun of justice,” Mustafa Ali wrote.15

Justice was no mere rhetorical ideal. It was the basis of the Ottoman dynasty’s legitimacy. Descended from Central Asian migrants, the Ottomans could make no dynastic claim to rule as descendants from the Prophet. Instead, they claimed rule as defenders of the faith, whose army and law would establish Islamic justice throughout the realm.16 Sultans performed justice by issuing decrees (adaletnameler) that set out a code of conduct for bureaucrats. In 1595, for example, the new sultan Mehmed III issued a justice decree ordering tax...