![]()

CHAPTER 1

Too Too Utterly Utter

On a wintry gray afternoon on the day after New Year’s, 1882, a chilled boatload of newspaper reporters in a chartered launch thrashed across the waves in New York harbor toward the steamship Arizona, sitting at anchor off Staten Island. Night would be falling soon, but the journalists couldn’t wait for the ship to clear quarantine the next morning. They were after answers to the burning questions: “Why have you come to America?” and “Do you really eat flowers for breakfast?”

The object of the reporters’ quest was waiting serenely in the captain’s quarters, utterly indifferent—or at least carefully feigning indifference—to the media storm about to engulf him. Oscar Wilde was used to such attention. By the time he arrived at the watery edge of America, he had already achieved a certain level of fame in England for his outlandish antics and deliberately provocative appearance. In late-Victorian-era London he was a walking, talking affront to polite society—all the more shocking since he came from a privileged background himself. The son of a prominent if eccentric Irish physician and an equally well-known and eccentric poet and political activist, Wilde had been raised in a hothouse atmosphere of artistic pretensions and personal license. His father, Sir William Wilde, had unapologetically fathered several illegitimate children before his marriage and, to his credit, continued to support them financially and professionally. One of them, Dr. Henry Wilson, eventually became director of the private hospital that Sir William had founded in Dublin. Meanwhile, Wilde’s mother, Lady Jane Elgee Wilde, filled the household on Merrion Square in Dublin with a steady stream of artists, writers, actors, musicians, professors, and politicians, all of whom were expected to get up and perform for the other guests. Rumored to have had clandestine affairs herself, she was an outré presence in trailing scarves and jeweled turbans. “There is only one thing in the world worth living for,” she said, “and that is sin.”1

Despite their personal peccadilloes, Wilde’s parents were both successful—even driven—individuals, traits their second son would eventually display himself. Sir William was one of the leading eye and ear specialists in Great Britain, authoring several comprehensive textbooks in his field of study. In 1863 he was appointed Surgeon Oculist to the Queen in Ireland, which meant that if Her Majesty visited the Emerald Isle again and got a sty or a coal cinder in her eye, he would be the one to remove it. She never made the return trip while he was alive, having gotten her nose out of joint over the refusal of the Irish people to place a statue to her dead husband, Prince Albert, in St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin, and rename the park Albert Green. Perhaps it was for the best. There were rumors that Sir William, during a visit to Sweden, had operated on the king’s eyes and, while the monarch was temporarily blinded, had made love to the queen. Apparently, there was nothing to the rumor, but Crown Prince Gustav, on a later visit to Dublin, joked that he was Oscar Wilde’s half-brother. Wilde never bothered to deny it.

Lady Jane concentrated more on affairs of a political nature. She was an early and enthusiastic convert to the cause of Irish nationalism, contributing inflammatory poems and barricade-raising editorials to the Nation on such topics as the great potato famine and the mass exodus of Irish men and women to America. She adopted the pen name Speranza, meaning “Hope” in Italian, and began calling for armed rebellion against England, declaring that “the long pending war with England has actually commenced” and yearning for “a hundred thousand muskets glimmering brightly in the light of Heaven.” On St. Patrick’s Day, 1859, she attended the Lord Lieutenant’s Ball in full patriotic rig: white silk skirts tied with white ribbons and bouquets of gold flowers and shamrocks. “Ah, this wild rebellious ambitious nature of mine,” she wrote. “I wish I could satiate it with empires.” Instead, she ruled over a somewhat smaller domain of talkers, arguers, disputers, and debaters, of whom she counted herself first among equals. “I express the soul of a great nation,” she informed a fellow poet, adding that she was “the acknowledged voice in poetry of all the people of Ireland.” Like her famous son, she knew how to make an entrance. “I soar above the miasmas of the commonplace,” she cried. It is no accident that Oscar Wilde’s plays are populated by witty, expressive, and formidable women. “All women become like their mothers,” he would write. “That is their tragedy. No man does. That is his.”2

Wilde’s parents saw to it that he and his older brother, Willie, attended the best schools, starting with Portora Royal Academy in Enniskillen. (The Wildes’ only daughter, Isola, the pet of the family, died of a fever when she was nine.) Portora styled itself “the Eton of Ireland” and specialized in sending boys to Trinity College in Dublin. Wilde soon outstripped his wastrel older brother academically, if not socially, winning prizes for poetry, Scripture, and Greek studies and moving on to Trinity on a full scholarship. From Trinity he passed effortlessly to Magdalen College at Oxford, where he studied under celebrated professors John Ruskin and Walter Pater and, almost as an afterthought, won the school’s prestigious poetry award, the Newdigate Prize, for his Byronesque 1878 poem “Ravenna.”

From the start of his undergraduate career, Wilde affected an airy indifference to formal education. Higher learning, he said, meant little to him, since “nothing that is worth knowing can be taught.” He embarked instead on his own course of study at Oxford, which amounted chiefly to finding the best way to nurture his carefully cultivated image as an artist and make an immediate impression on all he met. He wore loud plaid suits, too-small bowler hats, and robin’s egg-blue neckties, carried around dog-eared volumes of Dante’s and Whitman’s poetry, and began a lifelong habit of cigarette smoking. “I find it harder and harder every day to live up to my blue china,” he sighed theatrically, decorating his undergraduate rooms with Japanese fans, silk screens, peacock feathers, and artfully draped curtains. Fresh-cut lilies perfumed the air. His china cabinet held a table-buckling array of exquisite pieces: two large blue china vases, two blue mugs, four soda-water tumblers, four plain tumblers, six port glasses, six gilt coffee cups and saucers, six Venetian bock glasses, two green Romanian claret decanters, one plain claret decanter, and six ruby champagne tumblers. Thus suitably equipped, Wilde hosted regular Sunday evening receptions, called “beauty parties,” where tiptoeing servants in felt slippers proffered guests brimming bowls of gin-and-whisky punch, long pipes stuffed with choice tobacco, and cream-cheese-and-cucumber sandwiches. Wilde was called “Hoskie” by his classmates; his best friends were nicknamed “Bouncer” and “Kitten.” Everything and everyone, he said in a phrase that soon swept the university and beyond, was “too too utterly utter” for words.3

Wilde embraced the social life at Magdalen (pronounced “Maudlin” in the English way), but haughtily avoided competitive athletics. Of Oxford’s famously hearty oarsmen, he complained: “This is indeed a form of death, and entirely incompatible with any belief in the immortality of the soul.” He failed to see the use, he said, of “going down backwards to Iffley every evening.” Asked which sports he preferred, he replied: “I am afraid I play no outdoor games at all. Except dominoes. I have sometimes played dominoes outside French cafés.” After breaking his arm in a pickup soccer game, he was moved to observe: “I never like to kick or be kicked. Football is all very well as a game for rough girls, but for delicate boys it is hardly suitable.” If the later accounts of fellow students are to be believed, Wilde was not quite so delicate as he let on. At least two of his classmates passed along stories of the burly Wilde besting, or at least holding his own, in fisticuffs with bullying upperclassmen. All his life he seldom backed down from a fight, whether verbal or physical.4

Despite his professions of academic indifference, Wilde surprised everyone, including himself, by graduating from Oxford in 1878 with a rare double “first” in classics and modern literature. Like other matriculating seniors, then and later, he drifted a bit after graduation. He applied unsuccessfully for postgraduate scholarships in Greek and archaeology, failed to win a somewhat déclassé appointment as a school inspector, and hung around the fringes of college life, helping to costume and mount a performance, in the original Greek, of Aeschylus’s Agamemnon. Finally, with the help of a small inheritance from his late father’s estate, he moved down to London in early 1879 and immediately set out to conquer society, telling a school friend prophetically, “Somehow or other I’ll be famous, and if not famous, I’ll be notorious.” In short order, he was both. Walking along the streets of the capital one day, he heard someone mutter, “There goes that bloody fool Oscar Wilde.” “It is extraordinary how soon one gets known in London,” he said happily.5

Wilde quickly became the public face of the Aesthetic Movement, a loosely organized, something-for-everyone grab bag of painters, writers, architects, and home decorators that was sweeping across England at the time. The Aesthetes were direct descendants of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which under the leadership of poet-artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and cofounders William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais had emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century as England’s first truly avant-garde movement. The Pre-Raphaelites, like the doomed Romantic poets they worshiped, championed individuality, nature, and freedom of expression, even as they signed their works with a communal “PRB.” An early and enthusiastic supporter was Wilde’s future Oxford professor John Ruskin, who gamely continued to support them after his own wife, Effie, left him and ran off with Millais. (Understandably, Ruskin drew the line at supporting Millais.) Wilde later praised the Pre-Raphaelites as young men who “had determined to revolutionize poetry and painting,” even though “to do so was to lose, in England, all their rights as citizens. They had those things which the English public never forgives—youth, power and enthusiasm.” He could have said much the same thing about himself.6

The Aesthetes, following a generation after the Pre-Raphaelites, also championed art for art’s sake, stressing sensitivity, emotion, and what Wilde felicitously termed “the science of the beautiful.” Somewhat more democratic than the art school–based Pre-Raphaelites, the Aesthetes featured a strong handmade component to their philosophy, encouraging English craftsmen to simplify their work in furniture, textiles, glass, and ceramics. The recent craze for Japanese fashions, memorialized in Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera The Mikado, was incorporated into the movement. (The lily, an early trademark of Wilde’s, was first imported from Japan in 1862.) The Aesthetes extended their reach to home decorating, a reflection of the newly empowered middle class and its desire to be both respectable and au courant. In this they followed the lead of author and artist William Morris, who tirelessly lobbied for a return to handcrafted furniture and furnishings in the face of shoddy industrialized products. Sounding very much like Oscar Wilde two decades later, Morris declared that “the true secret of happiness likes in taking a genuine interest in all the details of daily life.” He practiced what he preached by personally designing and constructing, in 1860, a lavish new home in southeast London for himself and his family. Dubbed “Red House,” it was built with red bricks dating back to the Tudor era and meticulously decorated from top to bottom with handmade carpets, stained-glass windows, intricately designed wallpaper, wall hangings, and painted ceilings. Painter Edward Burne-Jones, who assisted Morris with the decorating, praised Red House as “the beautifullest place on earth.”7

The Great Exhibition in London in 1851, the first truly international world’s fair, had opened the eyes of the British public to a vast splendor of home furnishings and interior designs. An astonishing six million people, or one in every five English men, women, and children, attended the five-month-long exhibition. From giant machines to exotic birds, from furniture to lighting to wallpaper to china patterns, the crowds inside the Crystal Palace were overwhelmed by an embarrassment of riches—14,000 exhibits in all. It remained for the more aesthetically adept to differentiate for the British public the properly beautiful from the merely popular. Wilde, with his strong undergraduate interest in decorating and design, was more than willing to add his two shillings’ worth to the ongoing discussion. The long-standing, if usually misquoted, joke that Wilde on his deathbed shuddered, “Either that wallpaper goes or I do,” was merely a comic exaggeration of the seriousness with which the Aesthetes approached the subject of interior decoration.

The Aesthetes were at war with the very concept of Victorian furnishings. The heavy-legged furniture, dark-paneled woodwork, and over-stuffed rooms that constituted the typical upper-class home—and were being assiduously copied by the nouveaux riches of the middle class—offended Aesthetic sensibilities, which called for an altogether lighter, airier touch. Wilde would later sum up the battle for English homes in his essay “The Soul of Man under Socialism.” The problem, he wrote, was that “the public clung with really pathetic tenacity to what I believe were the direct traditions of the Great Exhibition of international vulgarity, traditions that were so appalling that the houses in which people lived were only fit for blind people to live in.” The Aesthetes, he said, would have to civilize them. Not everyone was convinced that such civilizing was necessary. Wilde’s friend Vincent O’Sullivan observed: “[Wilde’s] taste was not very sure, and it cannot be said that the result of his crusade was good. The practical application of Wilde’s aesthetic theories was Liberty gowns, and shoddy insecure furniture which soon became far uglier, as it was from the first far less comfortable than what it replaced. He forced solid British families to put out of doors the beautiful heavy Victorian furniture and curtains, so comfortable, so secure and to make their houses look like lawn tennis clubs on the Italian Riviera.”8

From the start, Wilde’s aesthetic sense mixed the teachings of his Oxford mentors Ruskin and Pater. Between them, Ruskin and Pater defined the opposite poles of English art criticism in the mid-nineteenth century. Ruskin, who was twenty years older, took the more rigidly moral approach to art, requiring that it address religious and social issues as well as purely artistic considerations. Pater, on the other hand, called for a more immediate and personal response to art, famously admonishing artists “to burn always with [a] hard, gem-like flame” and to evoke in their audience a similarly ecstatic response to their art. In the course of his own career, Wilde would fluctuate between the two poles, the formal and the personal. He praised Ruskin for combining “something of prophet, of priest, and of poet,” while at the same time telling William Butler Yeats that Pater’s groundbreaking Studies in the History of the Renaissance was “my golden book; I never travel anywhere without it . . . it is the very flower of decadence.”9

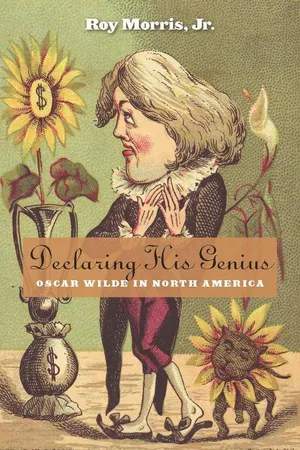

Whatever his artistic and critical influences, Wilde was soon the Aesthetes’ most visible proponent. As such, he became a frequent target for artist George Du Maurier of Punch magazine, who famously depicted Wilde as a flower-toting, world-weary dilettante with the ridiculous name of Jellaby Postlethwaite. Wilde played his part perfectly, dressing in crushed-velvet coat, satin knee breeches, black silk stockings, and pale green necktie, with a giant yellow-and-brown sunflower pinned to his lapel. He quickly became, in the words of one observer, “the most talked-about dandy since Beau Brummell.” It was a role he was naturally prepared to play. “Individualism,” he explained in his self-appointed role as Professor of Aesthetics, “is a disturbing and disintegrating force. Therein lies its immense value. For what it seeks to disturb is monotony of type, slavery of custom, tyranny of habit and the reduction of man to the level of a machine.” He was nothing if not an individual. Even Queen Victoria herself took notice of Wilde’s emergent celebrity, attending a performance of Punch editor Frank Burnand’s comedy The Colonel, whose fake poet, Lambert Streyke, was clearly modeled on Wilde. It was, said Her Majesty, “a very clever play, written to quiz and ridicule the foolish aesthetic people who dress in such absurd manner, with loose garments, puffed sleeves, great hats, and carrying peacock’s feathers, sunflowers and lilies.” Everyone knew about whom she was speaking.10

Du Maurier was merciless, picturing Postlethwaite at “An Aesthetic Midday Meal” consisting entirely of a glass of water for his fresh-cut lily. “I have all I require,” says the poet. In another sketch, a fainting Aesthete is revived by a St. Bernard dog in the Alps, where he has gone to look for the perfect flower after hearing that Postlethwaite had sat up all night contemplating a lily. “I have imitators,” brags Postlethwaite upon hearing the news. “Milkington Sopley swore he never went to bed without an aloe blossom.” In another famous drawing, Du Maurier depicted Postlethwaite outside a public bathhouse by the sea. Invited by an acquaintance to “take a dip in the briny,” Postlethwaite wanly declines. “Thanks, no,” he says. “I never bathe. I always see myself so dreadfully foreshortened in the water, you know.” So valuable was Du Maurier’s good-natured ribbing to the sudden spread of Wilde’s fame that American expatriate artist James McNeill Whistler, a sharp-elbowed rival of both, once cornered the pair at an art exhibit and demanded to know, not entirely in jest, “Which one of you discovered the other?” In an irony of literature, Du Maurier would later write the best-selling novel Trilby, whose main character, Svengali, creates a famous opera singer out of a tone-deaf street urchin as an act of willful provocation. He would also outrage his erstwhile friend Whistler, who threatened...