![]()

PART I

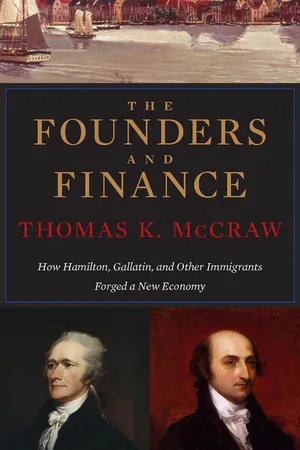

Alexander Hamilton 1757–1804

FIGURE 1. Statue of Alexander Hamilton overlooking the south plaza of the Department of the Treasury, Washington, D.C. Sculpted by James Earle Fraser, dedicated in 1923.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

St. Croix and Trauma

Of the six major “founders” of the United States, Alexander Hamilton was the only immigrant. He was also much the youngest of the six: fifty-one years younger than Benjamin Franklin, twenty-five younger than George Washington, twenty-two younger than John Adams, fourteen younger than Thomas Jefferson, six younger than James Madison. Hamilton alone died violently, in his famous duel with Aaron Burr. He also had the shortest life—only forty-seven years. Washington lived to be sixty-seven, Adams into his nineties, the other three into their middle eighties.

All were true revolutionaries. As Benjamin Franklin remarked in 1776, “We must all hang together or assuredly we shall all hang separately.” Yet as soon as the United States achieved independence, the revolutionaries began to quarrel with one another over the shape the new nation should take. In consequence, the 1790s, the first decade under the Constitution, was probably the most contentious period in American history except for the 1850s and 1860s, which brought the Civil War. And despite the romantic picture later generations painted of the founders, nobody escaped condemnation. Even George Washington almost quit public life because of the partisan infighting. The founders attacked one another without mercy, often through newspaper articles and pamphlets they wrote under pseudonyms.

Alexander Hamilton, the visionary immigrant who shaped the nation’s future economy, absorbed more abuse than anyone else (and inflicted a good deal himself). The tasks assigned him and the audacity with which he pursued them guaranteed that this would happen. “Never,” he wrote in 1800, “was there a more ungenerous persecution of any man than of myself. Not only the worst constructions are put upon my conduct as a public man but it seems my birth is the subject of the most humiliating criticism.”1

. . .

Hamilton came from a complicated background that was certain to incite rumor and gossip. To this day, no one knows with complete assurance when or where he was born, or even who his father was. The year was likely 1757, as he himself believed, but may have been 1755, as one official record indicates. Not that it makes much difference. By all accounts he was a boy wonder. His birthplace was probably the small West Indian island of Nevis, near St. Kitts and St. Croix. At that time, Nevis contained about 1,000 whites and, to work the island’s sugar plantations, 8,000 enslaved blacks.2

Hamilton was the most romantic and dashing of the founders. He likely inherited his good looks—“a face never to be forgotten,” as one of his sisters-in-law called it—from his mother, Rachel Faucett, a beautiful woman of British and French Huguenot descent. She was a native of Nevis and a minor heiress. At sixteen she was married to Johann Lavien, a flashy but cruel Dane nearly twice her age. Together with her mother, who had arranged the marriage, Rachel then moved to Lavien’s home in St. Croix—the largest of the Danish Virgin Islands, lying about seventy-five miles southeast of Puerto Rico.3

A few years later, after bearing a son, the headstrong Rachel abandoned her husband, child, and mother. She began living on nearby St. Kitts with James Hamilton, the ne’er-do-well fourth child of an aristocratic Scottish family. Rachel and James did not marry, but Rachel gave birth to two sons, whom she named James and Alexander Hamilton.

In 1765, when James was about ten and Alexander (“Elicks”) eight, the family moved back to St. Croix. Not long afterward, the elder James Hamilton abruptly left the island, deserting his family and never seeing them again. Meanwhile, Johann Lavien had divorced Rachel on grounds of adultery. For that offense she spent two months imprisoned in a dank fortress, a harsh punishment even for that time and place. The divorce decree read that she had abandoned her husband and child and had “given herself up to whoring with everyone.” This was too cruel a judgment, but Rachel likely did have other lovers besides James Hamilton.4

After her release from prison, she opened a small store in St. Croix’s capital city of Christiansted, a port heavily involved in the sugar trade. She and her sons lived over the store, as was customary in eighteenth-century towns. For a while the little family got along fairly well. Elicks clerked in his mother’s shop and began to learn rudimentary lessons about business.

At that time the Caribbean sugar islands, despite their beauty, were among the unhealthiest places on earth. Their fetid conditions and sweltering climate gave rise to persistent yellow fever, malaria, and typhoid fever. Lifespans were notoriously short—for planters, slaves, and everyone else, including the large number of British sailors stationed in the West Indies.

Not long after their move to St. Croix, Elicks and his mother fell ill, probably with yellow fever. They lay in bed together in their small quarters, becoming sicker by the hour. After a few days, Rachel died as Elicks slept. He woke up to find her lifeless body. She was thirty-nine years old; Elicks, nine. A male cousin then adopted him and his brother, but soon afterward the cousin committed suicide. Within the same year, an aunt, uncle, and grandmother also died. Meanwhile, a court in St. Croix awarded Rachel’s property to the son she had borne to Johann Lavien. That son, now in his twenties, had moved to another island but returned to claim his inheritance—leaving Rachel’s two Hamilton sons destitute.

Such an extraordinary run of bad luck might have been almost laughable had it not been so tragic. The deep wounds the Hamilton boys suffered never healed. Nobody fully “gets over” experiences such as theirs. The adult Alexander Hamilton’s extreme sensitivity to insult, his frequent lack of discretion, his impulsiveness, and his pleasure in outsmarting his enemies had roots in the devastating psychological shocks of his youth.

After their mother’s death, James and Elicks were split up—still another blow to both of them. James was apprenticed to a carpenter and for the rest of his life had little contact with his brother. Elicks was taken in by the family of his young friend Ned Stevens. This gesture by the Stevens family, together with the uncanny physical resemblance of Ned and Elicks, led some people to speculate that he and Ned were not mere friends. They may have been half-brothers as well. Ned’s father had known Rachel for many years.5

Hamilton’s boyhood could hardly have been more different from those of the other founders—especially Washington, Jefferson, and Madison on their large Virginia plantations. Yet even at this stage, it was clear that Elicks had supreme intellectual gifts. By the age of nine, he had begun to show the boldness and self-reliance that would characterize his later years—an unblinking assessment of his circumstances and a resolve to master them. Denied the security and affection of a close family circle, indeed of much real childhood at all, he developed by his early teens a habit of focused, unremitting work. None of the other founders had greater powers of concentration or so little taste for leisure. And none except Franklin started working so early.

. . .

At the time Rachel died, St. Croix had a population of about 24,000, more than 90 percent of whom were enslaved. Hamilton’s close contact with so many human chattels almost surely shaped his ardent lifelong opposition to slavery. Sugar plantations dominated the island’s eighty-three square miles. (By comparison, Manhattan has twenty-three.) The culture of St. Croix, like that of the rest of the Caribbean, was stratified: a few wealthy planters at the top, enslaved masses at the bottom, and in between a motley group of traders, fortune seekers, and itinerant seamen. The small city of Christiansted, where Elicks lived, contained 3,500 people, only about 850 of whom were white. Most of the whites were of English and Scottish descent, plus a few officials from Denmark, which had acquired the island from France in 1733. Elicks grew up speaking English but became fluent in French as well, most likely from his mother’s teaching.6

After her death and his move into the Stevens household, he found a job in the local merchant house of Beekman and Cruger, New York–based traders. He worked under Nicholas Cruger, who was ten years his senior. The firm did a lively import-export commerce centered on the sugar economy, and Hamilton learned valuable lessons about business: bookkeeping, inventory control, short-term finance, scheduling, and the pricing of merchandise. He became an expert on the fluctuating exchange rates of the many different national coinages and currencies in circulation. He grew familiar with the bills of credit issued by numerous merchants.7

In all, his duties in the Cruger enterprise thrust him into adulthood. During one of Nicholas Cruger’s frequent absences, the fourteen-year-old Hamilton wrote detailed instructions to ship captains in the firm’s employ. One message warned a captain against the consequences of delay (the following documents are in their original spelling, as are all other quotations in this book):

ST. CROIX NOV. 16, 1771

Here with I give you all your dispatches & desire youll proceed immediately to Curracoa. You are to deliver your Cargo there to Teleman Cruger Esqr. agreable to your Bill [of] Lading, whose directions you must follow in every respect concerning the disposal of your Vessell after your arrival . . . Remember you are to make three trips this Season & unless you are very diligent, you will be too late as our Crops will be early in.

Then, three months later, upbraiding the same captain on his failures:

ST. CROIX FEBRU 1, 1772

Reflect continually on the unfortunate Voyage you have just made and endeavour to make up for the considerable loss therefrom accruing to your Owners.8

A letter Hamilton wrote at the age of twelve to his friend Ned Stevens captures his fervent drive and self-awareness. Among his thousands of surviving letters, this is one of the most revealing:

Ned, my Ambition is prevalent that I contemn the grov’ling and condition of a Clerk or the like, to which my Fortune &c. condemns me and would willingly risk my life tho’ not my Character to exalt my Station. Im confident, Ned that my Youth excludes me from any hopes of immediate Preferment nor do I desire it, but I mean to prepare the way for futurity. Im no Philosopher you see and may be jusly said to Build Castles in the Air. My Folly makes me ashamd and beg youll Conceal it, yet Neddy we have seen such Schemes successfull when the Projector is Constant I shall Conclude saying I wish there was a War.

Glory in war was practically the only route to distinction available to a boy of his situation at that time and place. He would soon get his war, and would make the most of it.9

In 1772, a powerful hurricane struck St. Croix, and the fifteen-year-old Hamilton’s account of it, published in the Royal Danish American Gazette, brought him some local notice: “It seemed as if a total dissolution of nature was taking place. The roaring of the sea and wind, fiery meteors flying about in the air, the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lightning, the crash of the falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed, were sufficient to strike astonishment into Angels . . . But see, the Lord relents. He hears our prayer. The Lightning ceases. The winds are appeased. The warring elements are reconciled and all things promise peace.”10

In addition to his gift for writing, the young Hamilton had a deep conceptual intelligence and first-rate analytical powers. Despite his almost complete lack of formal schooling, he also had a quick and cold-blooded facility with numbers. His job with the Crugers brought him into contact with people from ports throughout the Americas, as well as western Europe. The rest of his early knowledge about the outside world came from his mother’s excellent collection of books.

It was his work, however—and his being put in charge of the Cruger operation during his superior’s absences—that taught him the core principles not only of retail and wholesale management, but also of finance. These principles included the nature of credit and the importance of compound interest, ideas not well understood in that era even by many businesspeople. This knowledge and experience, acquired so early, played a big part in Hamilton’s future triumphs as U.S. secretary of the treasury.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

New York and Promise

In the eighteenth century, it was common practice in the West Indies to help talented white boys go abroad for further education. Hamilton had no family financial support other than that of his cousin Ann Lytton Venton, whom he later called “the person in the world to whom as a friend I am under the greatest Obligations.” But he made the journey to North America with the additional help of several St. Croix sponsors who had been impressed by his account of the great hurricane. Among them was Hugh Knox, a radical Presbyterian minister with connections in New York and New Jersey.1

Bearing letters of introduction to prominent families in those two colonies, Hamilton sailed away from St. Croix in October 1772. He was fifteen and a half years old and looked even younger because of his small size. Hugh Knox’s wealthy friend William Livingston welcomed the young immigrant at his mansion in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. Hamilton studied for almost a year at a nearby Presbyterian school run by a recent graduate of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). He then tried to get into the same college himself but was denied admission. In the fall of 1773, he enrolled as one of seventeen first-year students admitted to King’s College (now Columbia University), which at that time was located in lower Manhattan. He was not a regular member of the class but attended as a private student of anatomy, Latin, and mathematics.

He also read the classics—Plutarch’s Lives in particular—as well as more recent works by Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Blackstone, and Hume, all of whom influenced his future writing. His friends at King’s College remembered him as studious and given to composing doggerel verses. (Hamilton had a sense of humor, but he seldom allowed it to surface, then or at any other time.) They also recorded a habit of his that stayed with him for the rest of his life: pacing back and forth in his rooms for hours, talking to himself—composing oral arguments as he worked out problems of logic and presentation. In all, he was a striking, zealous, and altogether memorable young man.2

Hamilton was fortunate in settling in New York rather than, say, Boston or Savannah. Since the period of the initial Dutch settlement—16...