![]()

chapter one

Black Literacy in the White Mind

THOMAS DUCKET INSISTED he was innocent. After slave catchers seized the schooner Pearl, which was carrying seventy-six fugitives down the Potomac River, slaveholders in Washington, D.C., scoured the city for conspirators. Desperate to know who had funded and orchestrated one of the largest escape attempts in the history of American slavery, they interrogated the fugitives, put the ship’s captain on trial, and harassed other slaves. Ducket was guilty by association: his wife and children had been captured aboard the Pearl. His owner suspected he was among the plotters of the escape, or at least knew who they were, and resolved to sell Ducket to the Deep South—the severest of punishments in the eyes of most enslaved Washingtonians. The accused slave’s protests of innocence came to nothing, nor did his single plea: if he must be sold away, might he at least be sold to the same person who purchased his family? Ducket’s owner may have openly rejected his request or he may have feigned to honor it, allowing Ducket to depart Washington with false hope of a reunion with his wife and children.1

By the time he arrived on a plantation in southern Louisiana, Ducket no longer harbored illusions about his fate. He had indeed suffered what the domestic slave trade portended for most of its victims from the Upper South: consignment to grueling labor and a diminished life expectancy in the Lower South’s cotton or sugarcane fields; the near impossibility of escape; and, what Ducket most dreaded, permanent separation from family and friends. In the antebellum American imagination, as in the well-founded fears of millions of slaves, to be sold farther south was to descend into greater suffering, isolation, and enforced ignorance—including illiteracy. As Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom was carried down the Mississippi River and away from his family, he found fewer opportunities to practice his reading and writing. In the barbaric domain of Simon Legree, even the marked passages in Tom’s own precious Bible no longer reached his “failing eye and weary sense.”2

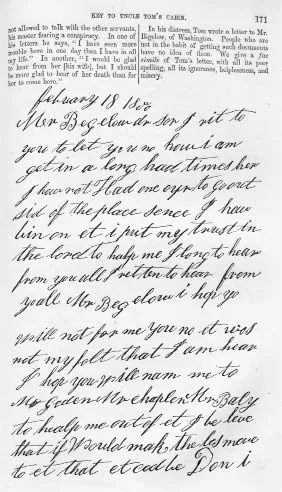

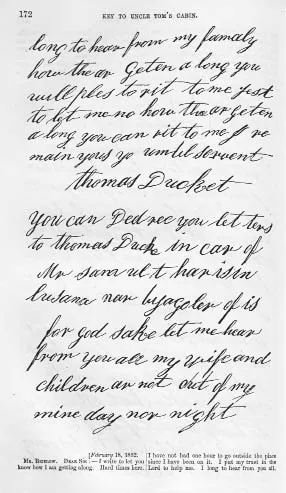

Abolitionists regularly denounced white southerners for withholding the light of knowledge from their slaves, but the institution’s pall of mental darkness, though nearly overwhelming, was not total. Even on the banks of the lower Mississippi years before emancipation, a slave might take up a pen and write. Thomas Ducket did it on February 18, 1850. Desperate to find his lost family, Ducket wrote a faltering plea to Jacob Bigelow, a white abolitionist back in Washington:

Mr Begelow dr sir I rit to you to let you no how i am get in a long had times her I have not Had one our to go out sid of the place sence I hav bin on et i put my trust in the lord to halp me I long to hear from you all I ret ten to hear from yo all Mr Begelow i hop yo will not for me you no et was not my falt that I am hear I hop you will nam me to Mr Geden Mr chaplen Mr Baly to healp me out of et I be leve that if Would mak the les move to et that et cod be Don i long to hear from my famaly how the ar Geten a long you will ples to rit to me jest to let me no how the ar Geten a long you can rit to me I re main yous yo umbl servent

thomas Ducket

you can Ded rec you let ters to thomas Ducke in car of Mr samul t harisin lusana nar byaGoler of is for God sake let me hear from you all my wife and children ar not out of my mine day nor night3

Evidently Ducket was acquainted with Bigelow back in Washington and also was familiar with other opponents of slavery (“Mr Geden Mr chaplen Mr Baly”: Jacob Giddings, William Chaplin, and Gamaliel Bailey, each of whom was thought to be implicated in the Pearl affair), which may suggest that Ducket indeed was involved with the escape plot. Nevertheless, the injustice of his punishment remains: “you no et was not my falt that I am hear.” Exiled to a plantation near Bayou Goula, Louisiana, Ducket is not allowed “one our to go out sid of the place,” and his forsaken “wife and children ar not out of [his] mine day nor night.”

Whether Ducket found his family, or even received a reply, remains unknown. Only against long odds has his letter even survived. A barely intelligible missive scrawled by an enslaved hand, improbable to begin with, would not have struck many people at the time as an artifact worth preserving, and the original manuscript indeed does not survive. We have Ducket’s letter only because Harriet Beecher Stowe wanted her millions of readers to see it. Following vociferous attacks by southerners on Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the best-selling novel of its time, Stowe undertook to present the reading public with evidence that would validate her novel’s representation of slavery. She gathered various sources, ranging from letters to newspaper clippings to legal papers, that provided a glimpse inside the institution, and she published her findings in 1853 as A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Presenting the Original Facts and Documents upon Which the Story Is Founded, Together with Corroborative Statements Verifying the Truth of the Work. While she was working on A Key, Stowe received additional materials from friends and supporters, including Jacob Bigelow, who passed along the letter he had received from a marginally literate slave.

A text penned by someone still suffering in slavery was scarcely thinkable in the 1850s, and to Stowe, the surprising example that arrived on her desk remained largely unreadable. Intent on conveying Ducket’s palpable suffering and the depth of his devotion to his family, Stowe regularized the letter’s prose when she transcribed it into a chapter of A Key. She added punctuation, corrected spelling, and supplied a few missing words (“I hope you will not forget me” for “i hop yo will not for me,” and “if they would make the least move” for “if Would mak the les move”). In addition to making the letter easier to read, though, Stowe insisted on showing just how poorly written it originally was. She took the unusual step of having a reproduction of the handwritten letter published along with her transcription. Convinced that the material document revealed as much as its text, Stowe introduced it with these words: “We give a fac simile of Tom’s letter, with all its poor spelling, all its ignorance, helplessness, and misery.”4

Facsimile of Thomas Ducket to Jacob Bigelow, February 18, 1850, from Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1853), 171–172. Courtesy of the Watkinson Library, Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut.

As Stowe implies, Ducket’s crooked lines and shaky penmanship testify to the anguish of his enslavement at least as forcefully as the story he tells. His “poor spelling” and “ignorance” are part and parcel of his “misery,” and what Stowe finds appalling is not that Ducket has been deprived of literacy but that his literacy has been deformed. In a gruesome counterpoint elsewhere in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe quotes slaveholder Micajah Ricks’s 1838 newspaper advertisement seeking the return of his fugitive slave: “Ran away, a negro woman and two children; a few days before she went off, I burnt her with a hot iron, on the left side of her face. I tried to make the letter M.” Stowe comments: “It is charming to notice the naïf betrayal of literary pride on the part of Mr. Ricks. He did not wish that letter M to be taken as a specimen of what he could do in the way of writing. The creature would not hold still, and he fears the M may be ilegible [sic].” Stowe finds that both these texts, the terrible alphabetic wound and Thomas Ducket’s labored supplication, have power precisely because they are difficult to read. Arrested literacy shows the suffering and sentiments of the enslaved—the “helplessness” in Thomas Ducket’s dual inability to spell or to find his family; the terrified, fierce resistance (she “would not hold still”) revealed in the attempted M on the runaway’s cheek. The written word proves less important for what it says than for what it falls short of saying.5

In preparing her compendious documentary account of southern slavery, Stowe encountered evidence of slave literacy that few northerners had ever seen, and that even she found challenging to understand. To most white Americans of the antebellum era, writing by those who were currently enslaved was scarcely conceivable. From a northern perspective, the chances for slaves’ writing were buried in the abyss of slavery’s brutality or the supposed backwardness of southern culture. For many southerners, the possibility of slave literacy was covered over by their own illusions or their slaves’ secrecy. Whether sympathetic or indifferent to the plight of slaves, free Americans before the Civil War knew they were living within a paradox: their society valorized education, abounded in books, and relished the written word, yet it tolerated the legal prohibition of literacy for millions of African Americans. In myriad ineffable ways, that contradiction affected the imagination of writing in the mid-nineteenth-century United States. Unmistakably, it obscured the role writing actually played in the lives of enslaved people, and that obscurity, passed down with the rest of our cultural inheritance from antebellum America, continues to inform our thinking. Most scholars today esteem slaves’ literacy as a form of resistance and a means of escape but neglect the ordinary acts of writing—often faltering and agonized—that were part of life in slavery. To begin the process of making those acts intelligible, we first need to unravel the misapprehensions of white observers.6

Between 1830 and 1860, the political debate over slavery intensified, with both sides becoming radicalized. By the 1850s, slaveholders and their apologists, once apt to characterize the institution as a necessary evil, now painted an idealized picture of it as a “positive good”—a divinely ordained relation of harmony between benevolent masters and puerile slaves. Meanwhile, abolitionists amplified their condemnations of slaveholders’ mendacity and barbarousness. To acknowledge that some slaves enjoyed the limited autonomy necessary to acquire a modicum of literacy, not to mention to commit their thoughts to paper, would have tempered both sides’ characterizations. Anti- and pro-slavery forces constructed narratives about literacy that served their political ends better than they represented slaves’ experiences.7

Ironically, many slaveholders ranked among the nineteenth century’s most committed believers in the importance and liberating potential of the ability to write. They tacitly acknowledged a form of racial equality that almost no one else did: if African American slaves acquired literacy, they could be expected to use it more or less as white people did—to communicate with each other and speak their minds. They especially would use it, southerners feared, to rebel or escape. Soon after Frederick Douglass began receiving elementary reading lessons from his white mistress, Sophia Auld, her husband forbade her to continue teaching Douglass, calling it “unsafe.” Most significantly, as one reader of Douglass’s autobiography points out, Mr. Auld “does not say, as public racist discourse of the period would dictate, that Mrs. Auld’s efforts are futile because of Frederick’s innate biological inferiority.”8

In Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1856 novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, Anne Clayton, a well-to-do North Carolina woman, teaches her slaves to read and write, in defiance of the laws of her state. When a family friend, Mr. Bradshaw, visits her to discuss the matter, their conversation sketches out two common views of slave literacy. Affecting politeness, Bradshaw speaks on behalf of worried and angry plantation owners in Clayton’s neighborhood:

“We appreciate your humanity, and your self-denial, and your indulgence to your servants. Everybody is of opinion that it’s admirable. You are really quite a model for us all. But, when it comes to teaching them to read and write, Miss Anne,” he said, lowering his voice, “I think you don’t consider what a dangerous weapon you are putting into their hands. The knowledge will spread on to other plantations; bright niggers will pick it up; for the very fellows who are most dangerous are the very ones who will be sure to learn.… You see, Miss Anne, I read a story once of a man who made a cork leg with such wonderful accuracy that it would walk of itself, and when he got it on he couldn’t stop its walking—it walked him to death—actually did! Walked him up hill and down dale, till the poor man fell down exhausted; and then it ran off with his body. And it’s running with its skeleton to this day, I believe.”

And good-natured Mr. Bradshaw conceived such a ridiculous idea, at this stage of his narrative, that he leaned back in his chair and laughed heartily, wiping his perspiring face with a cambric pocket-handkerchief.

“Really, Mr. Bradshaw, it’s a very amusing idea, but I don’t see the analogy,” said Anne.

“Why, don’t you see? You begin teaching niggers, and having reading and writing, and all these things, going on, and they begin to open their eyes, and look around and think; and they are having opinions of their own, they won’t take yours; and they want to rise directly.”9

Perhaps Anne Clayton is merely being coy. She may grasp Bradshaw’s analogy entirely but refuse to credit the implication that black literacy will “walk” white slaveholders “to death.” Perhaps, though, she genuinely does not “see the analogy”—does not understand how black literacy resembles the cork leg. Clayton, like Stowe’s sympathetic readers, wants her slaves to know how to read so they can study the Bible and achieve Christian salvation. As she sees it, literacy is not an instrument of rebellion, perhaps not of any kind of autonomy; it serves to integrate readers into a religious community. To conceive of black literacy as a prosthesis with a life of its own is to understand the act of reading and writing as a catalyst of individual development and resistance. Like Mr. Bradshaw, pro-slavery interests recognized—and feared—that possibility. Like Anne Clayton (an anomalous southerner), white northerners were generally unable or unwilling to see it the same way.

In the experience of most abolitionists—most middle-class northerners, in fact—learning to read and write did not foster radicalism. On the contrary, literacy brought children into the fold of Christian belief, taught them morality and manners, and generally helped them assimilate their culture’s values. Accordingly, anti-slavery rhetoric tended to decry the forced illiteracy of slaves not because it violated their individual rights but rather because it excluded them from the broader community of Americans and Christians. Only the most extreme abolitionist would have argued that slaves should be granted an education so that they would be empowered to revolt against their masters. Most of slavery’s white opponents believed in literacy’s more benign advantages.10

Most commonly, anti-slavery arguments pointed out that slaves’ illiteracy deprived them of access to religious scripture—an appalling fact in a society increasingly dominated by evangelical Protestantism. An abolitionist child...