![]()

Part 1

Women and samba

If art is a mirror of society, then we can see from the roles women play in the samba environment that much has changed in Brazil, but there is still a long way to go. From the birth of the rhythm through its evolution into a national symbol, the vast majority of samba composers and instrumentalists were men. One of them, Moacyr Luz, suggested an explanation. A renowned musician who has had more than one hundred of his songs recorded by some of the most famous Brazilian artists, such as Maria Bethânia, Gilberto Gil, Beth Carvalho, and Zeca Pagodinho, Luz once told me that “women don’t write sambas because they don’t go to bars.”1 Men create songs over beers and peanuts, and Brazilian society just does not allow women to be part of such an environment. They can be singers, muses, or both, but creating melodies and writing lyrics are usually reserved for men. Carmen Miranda, Elis Regina, Araci de Almeida, Clara Nunes, Linda Batista, Clementina de Jesus, Beth Carvalho, Alcione, and many other musical artists have included samba in their repertoires. Very few of these women, however, have been giving voice to their own compositions.

Another conventional role for women in the samba scene is the important figure of the tias (aunties, in English).2 An auntie is not a muse or a singer, but a kind of counselor. Hilária Batista de Almeida—better known as Tia Ciata—is the most renowned of them. She was a cook from Bahia who moved to the neighborhood of Praça Onze in Rio de Janeiro in the 1870s.3 João do Rio, a homosexual journalist of African descent who chronicled Rio de Janeiro’s poor areas in the early twentieth century, called her “a black of low character, vulgar, and presumptuous.”4 He described her role in Candomblé—which combines Roman Catholic, African, and indigenous Brazilian components—with contempt and fear: “The people of her town say that she has driven a distinguished lady crazy, by giving her a mix for a certain disease of the uterus.”5

The area of Praça Onze was celebrated as “Little Africa,” and Ciata made daily efforts to keep it worthy of the nickname. She hosted events such as Candomblé rituals, and parties wherein groups of musicians came together to experiment, improvise, and taste African food. Artists and composers came from far and wide to introduce their most recent creations. Her house became the mecca of African culture in the then capital of Brazil and is now considered one of the birthplaces of samba. “Pelo Telefone” (By Phone), deemed to be the first song of the genre, was composed there in 1916. There were other prominent female figures in the area at the time, but it is Ciata who is remembered today as the godmother of samba. Lira Neto states that, actually,

just like many other black women [who were] treated with reverence as tias by the community—Tia Bebiana, Tia Celeste, Tia Dadá, Tia Davina, Tia Gracinda, Tia Mônica, Tia Perpétua, Tia Perciliana, Tia Sadata, and Tia Veridiana—Ciata had a leading role in the community and an unquestionable leadership in the daily lives of all residents of the neighborhoods of Saúde, Cidade Nova, and Gamboa.6

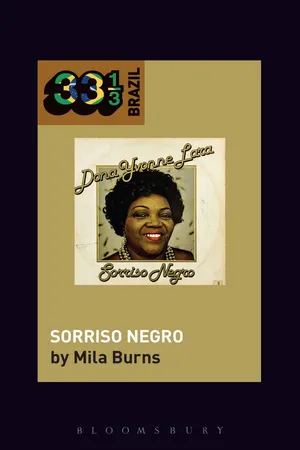

Even today, samba schools pay homage to Tia Ciata in the ala das baianas, which is mandatory in all parades.7 Dona Ivone Lara was a member of this wing from a young age. In the show to launch Sorriso Negro, she wore a beautiful, heavy dress that was typical of a baiana. The critics acknowledged the power of such a tradition, stating that it created an impact when she entered the stage. However, they complained it was “beautiful for a carnival parade, but ruined Lara’s dance.”8 There are still many tias in samba schools today. They are most often elderly women who have dedicated many years to the school and now enjoy some influence, but not necessarily great authority. The honorary title confers respect but no formal decision-making powers.9

It was—and still is—in the houses of the tias that the samba community got together for endless rodas de samba. Just as in the time of Tia Ciata, during Lara’s active professional years composers continued to use these occasions to showcase their new songs, or even to write in-loco pieces that would later become hits in the samba world. The mouthwatering smell of feijoada, the cold beer, and the simple tables around the backyard formed the perfect setting for powerful networks of socialization.10 In post-slavery Brazil, the dynamics of the traditional bourgeois family did not apply to most of the African and Afro-Brazilian families. Not only were women in charge of raising kids and working inside the house but they also had to join the labor market, frequently in informal jobs. Tia Ciata was one of many women from Bahia who brought to Rio de Janeiro the tradition of forming groups of organized workers in small and casual business such as food trade, sewing services, and rental of carnival clothes. Mônica Pimenta Velloso explains that this experience in the job market “influenced the personality of these women, changing the way they thought, felt, and integrated with reality. In contrast with women from other social segments, they behaved uninhibited and had a looser language and greater freedom of locomotion and initiative.”11

The tias were the hosts and bosses of their houses. They were the rulers of the place where sambas were created, cocomposers met, and decisions about the future of samba schools were made. Women, therefore, have been a crucial part of the history of samba since its very early days, but only as community organizers, performers, or simply as inspiration for male songwriters. Dona Ivone Lara, however, was not a tia, a singer, or a muse. She wrote songs and sang them. It is difficult to find an appropriate title for her, which in itself demonstrates how peculiarly male chauvinist the samba environment is. Lara became known as the “first-lady of samba,” primeira-dama, a title that completely contradicts her pioneering work and her independence as a composer, since it implies the presence of a strong man beside her, a male “head of state.”

A Sereia Guiomar

Half-woman, half-fish, a mermaid (sereia, in Portuguese) is a mythical creature that appears in the popular culture all over the world. They are frequently perceived as treacherous beings who can seduce and destroy. In Brazilian folklore, the most famous of these mighty creatures is Iara, which means “lady of the water” in Tupi.12 Iara has another characteristic that is somehow indicative of the Brazilian societal expectations for women: she sings. Her irresistible voice attracts men to the bottom of the river, draws them to their certain death. The few who can survive her approach end up mad, destroyed by her enchantments. Lara’s decision to open the album with “A Sereia Guiomar” (The Mermaid Guiomar) is deeply related to her admiration of a strong Brazilian woman, Maria Bethânia. They became good friends in 1978, when Bethânia recorded Lara’s “Sonho Meu” (My Dream) with another symbol of baianidade, Gal Costa. The tune became a hit and helped Bethânia’s album Álibi sell more than a million copies, a first for a woman in the country. It also turned Lara into a celebrity even beyond the samba environment.

It all started with a mutual friend, guitar player and composer Rosinha de Valença, who introduced Maria Bethânia to the song “Sonho Meu.” A few years later, Lara’s friendship with Valença would produce more fruits. Valença made the musical arrangements for most of the songs of Sorriso Negro and was the conductor for several of them. Her influence can be heard throughout the album. Born in the city of Valença, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, the acoustic guitar player was a prodigy. She was only 12 years old when she began to play in local events. Ten years later, Valença moved to the city of Rio de Janeiro and very soon became a fixture in the legendary Beco das Garrafas, an area full or nightclubs where the most famous musicians in the country performed. There, she met musical producer Aloysio de Oliveira, the director of record label Elenco.13

Oliveira was so astonished by Valença’s talent that he not only invited her to record her first album, Apresentando Rosinha de Valença (Introducing Rosinha de Valença), but also asked her to produce it. It was 1964, and she became respected in a male-dominated environment. Being a woman intensively influenced her playing. In an interview in 1972, she said:

I was a woman who needed luck because I was the only one dealing with a huge number of male acoustic guitar players, a bunch of men who were not about to give me a place. I almost had to pull the strings off the guitar so people would understand that I could play. I don’t know how many times did I purposefully play the chords very strongly to wake people up, so they would shut up a little and pay attention: when an artist plays he has to be heard. It does not matter if you’re wearing a skirt or a brief.14

Valença and Lara had experienced similar challenges in life, and they connected immediately. In Sorriso Negro, it is clear that they communicated musically as well.

Zé Luis Oliveira, a Brazilian composer, saxophonist, flutist, producer, and arranger, was very active in the early 1980s, having recorded and performed with Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa, and Cazuza. He also played with Rosinha de Valença and thinks her arrangements and conducting are key to threading songs in Sorriso Negro. “There are instruments not very typical of samba at that time, and also the melodic patterns, the voicings, and the harmony are all very sophisticated.”15 “A Sereia Guiomar” begins with an instrumental introduction that evokes the smell of salted water. The nautical atmosphere is the result of an affectionate conversation among flutes, a balafon (an African marimba), and a soprano saxophone. Just like the dialogue between Valença and Lara, this is a conversation between traditional samba and the new Brazilian popular music. “It also carries the duality of the 2/4 and the 6/8, which is a very African element,” explains Oliveira.

An ensemble of female voices sings the chorus “A Sereia Guiomar mora em alto mar” (The Mermaid Guiomar lives on the high seas), with Maria Bethânia’s voice a little louder than the others. Then Dona Ivone Lara sings alone “Como é bonito meu Deus” (How beautiful is it, my God), and the choir completes the verse “a lenda desta sereia” (The legend of this mermaid). It is an inspired flirtation with Bahia’s samba de roda 16 and Rio de Janeiro’s partido-alto, in which the main vocalist invites the audience to sing along, in a kind of call-and-answer pattern. In this duet, Bethânia and Lara take turns singing.17 The surdo—a large bass drum used in Brazilian music—keeps the partido-alto pattern throughout the song, while flute and soprano saxophone take turns counterpointing with the vocals, courting the Brazilian rhythms of choro and gafieira.18

Samba’s most basic rhythm has two beats, with four strokes each, in a 2/4 time structure. What gives it a unique swing is the syncopation, which means that the strong beat is suspended and the weak accentuated. Author Barbara Browning has described samba’s syncopation as the body saying what cannot be spoken: “This suspension leaves the body with a hunger that can only be satisfied by filling the silence with motion. Samba, the dance, cannot exist without the suppression of a strong beat.”19 For Muniz Sodré, the prolonged sound of the weak beat over the strong beat that creates the syncopated rhythm is a form of resistance, a way of pretending submission to the European tonal system while at the same time rhythmically destabilizing it. 20 He argues that syncopation is not a Brazilian invention and was present rhythmically in African music and melodically in Portuguese music. In a controversial argument, Sodré considers that the rhythm is more prevalent than the melody in samba, which is also a way of suggesting that its African heritage takes priority over its European.21

The encounter between Africa and Europe is apparent in Lara’s stage performances. Some consider samba to be a mix between African lundu and Portuguese modinha. Lara has a unique dance that became her trademark.22 She pulls up her long skirt, just enough to show her feet in small steps, reminiscent of the hops in jongo and Candomblé circles. The samba de roda follows a pulse similar to the African rhythm lundu, but at a slower pace. Indeed, Lara’s dancing style resembles the lundu dance, in which the performer steps firmly on the floor, adding another layer of percussion to the song.

In Dona Ivone Lara and Maria Bethânia’s performance of “A Sereia Guiomar” the wind instruments in the introduction indicate that hers is not a traditional take. The arrangements are reminiscent of Bethânia’s previous albums, in which several songs relied on wind instruments. The exception, then, were the songs composed by Lara, in which samba percussion instruments and electric keyboards prevail. In Bethânia’s album Álibi, “Sonho Meu” opens with the fingerpicking of an acoustic guitar, followed by a...