![]()

1

Introduction

Context

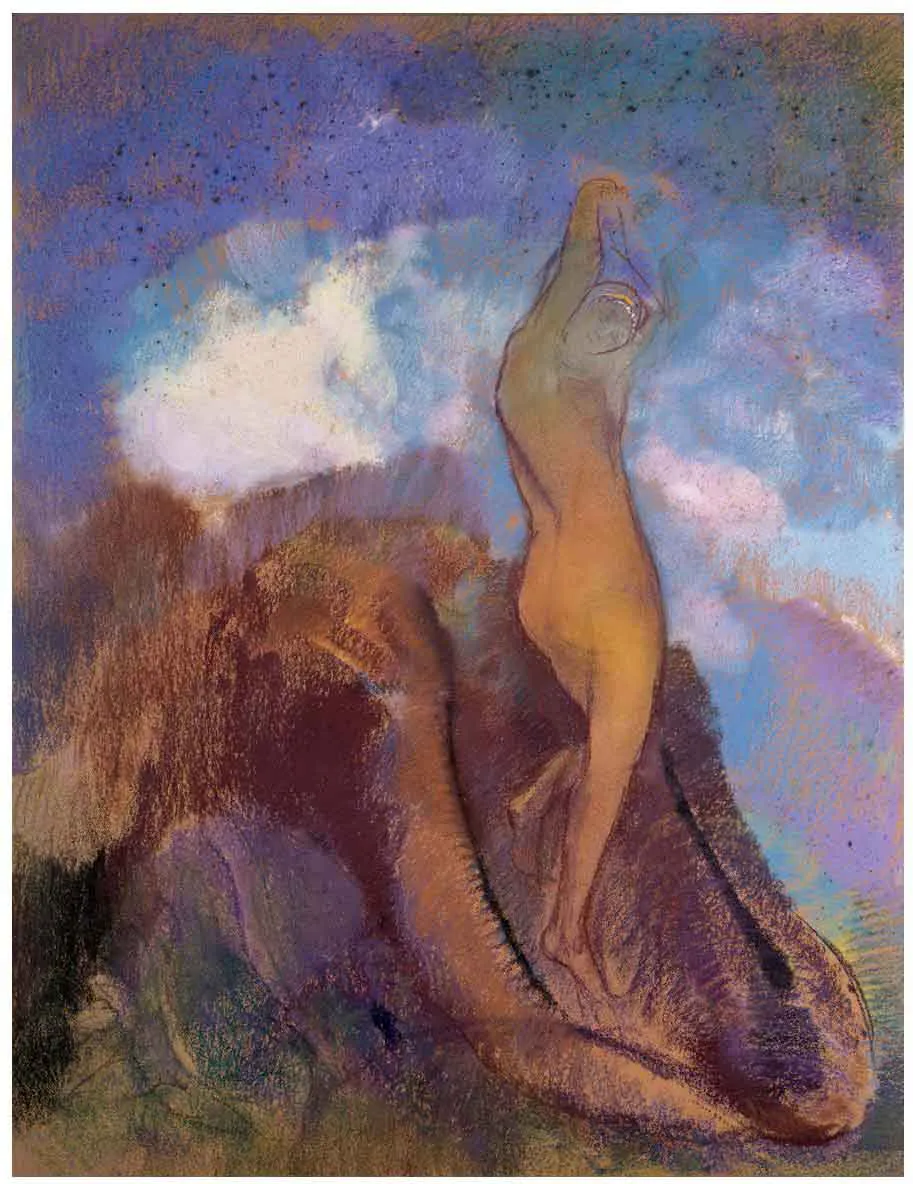

In 1912 the French Symbolist artist Odilon Redon (1840–1916) painted his The Birth of Venus1 (Figure 1).2 The goddess of love rises from the sea, a beautiful nude, radiantly bright and sensual. A perfect harmony of form and colour, entrancing, overpowering and ineluctable. Redon’s Venus is utterly emblematic of the concerns of this book. In it we trace how the Symbolists arrived at such an epiphany. But Venus’ is not only a birth. It is a re-birth. In Symbolist terms. For she perfectly encapsulates the quest for Greek sculpture reborn: the resurrection of an original Venus, one already born in antiquity and known in countless copies.3 And in that, its latest rebirth, love, the erotic – it has acquired a whole new level of power, one that is imbued with all the fin-de-siècle’s mystery, longing for the unattainable – unease, even.4

The end of the nineteenth century witnessed a revolution in European art. Or, more correctly put, a series of revolutions. This book considers one of these: the movement that styled itself ‘Symbolism’. Of the many, often mystic, preoccupations of the Symbolists, there is perhaps no single one that emerges so powerfully as the erotic. And, as this book argues, its adherents found that no symbolic language so powerfully expressed sexuality as classical myth and art. In our title, and throughout this book, we refer to the ‘Greek body’, in recognition of the fact that classical Greek sculpture – though they endlessly reinvented it – was a font of inspiration to the Symbolists. Recast in new media, blended with orientalism or transposed to mystic worlds, the essential erotic inspiration of the classics endured.

This book is about the Symbolist movement in art. Yet the artistic style had its origins in a literary movement. Who were the Symbolists? And what do we mean by Symbolism in art? Given the essentially elusive nature of Symbolism, any book on the movement must begin by answering these questions. Why elusive? Firstly, because Symbolist artists intended their art to be so. Symbolism was, as mentioned, primarily a literary movement, from which a series of artists in the last quarter of the nineteenth century – originally in France and Belgium, but before long as far afield as Russia – took inspiration. Both its literary and artistic manifestations may be considered a broad church of intellectual thought, and may best be considered through the personalities that defined them. Perhaps no single figure was as important to Symbolism as the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–67). In 1860s France, his revolutionary brand of poetry – above all in his The Flowers of Evil (1857) – sent shockwaves through his generation of writers and artists, and the following generation. The power of Baudelaire’s imagery, which did not shy away from portraying the deeper, and often darker, sides of human nature, provoked both admiration and contempt. But it was above all the allusive and metaphorical nature of Baudelaire’s poetry which was to exercise its most lasting influence. Taking their cue from Baudelaire, the generation of poets that followed – most seminally the Belgian poet Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–98), but also the Frenchmen Arthur Rimbaud (1854–91) and Paul Verlaine (1844–96), and the Belgian Emile Verhaeren5 (1855–1916) – set a new course away from both the Naturalism and the Realism of Victor Hugo (1802–85) and his followers, and from the studied Neoclassicism of the Parnassian poets. The Symbolists turned their attention away from this world, to focus on another – to a world beyond this world, a world shrouded from sight by the translucence of the material world, but one whose further reality might be dimly made out through the inspiration of poetry. That poetry could no longer simply be descriptive of the visible world. It must instead be a poetry of symbols. As in a dream, by alluding to what could not be directly expressed, those symbols would unlock deeper understanding and mystic insight.

Figure 1 Odilon Redon, The Birth of Venus. Courtesy Getty – Peter Willi.

The Symbolists were essentially a group of intellectuals who, while sharing this basic creed, interpreted it in a great variety of individual ways. And while deliberately divorced from reality, they were not divorced from contemporary currents of intellectual and artistic thought in the 1890s, engaging – often vigorously – with their contemporaries where their ideas diverged from their own. A number of figures may be more or less associated with the Symbolists who helped define its social and cultural milieu, and in this sense it is certainly possible to speak of a sort of fluid Symbolist circle. That circle was not always one that saw eye to eye with wider society. As Cassou (1988: 8) characterizes this dynamic:

There was a society within a society; it was a separate little society with its somewhat provocative manners which were bohemian, avant-garde, and only just acceptable. Its members had a very elevated idea of what constituted art and poetry outside a way of life which was firmly rooted in its bourgeois assurance, its order, its financial and industrial power, and the comforts which the unchangingly academic productions of its licensed tradesmen procured for it.

Indeed the French writer, critic and exponent of Symbolism Gustave Kahn (1859–1936) (1902: 22) found in its independence of societal and intellectual fashion one of Symbolism’s most important virtues:

Moreover, it must be pronounced, and very loudly, that one of the virtues of the emergent Symbolism was that it did not cave in before literary power, before titles, the open journals, friendships of note, and that it redressed the wrongs of the preceding generation.6

For Kahn (1902: 51–2), those wrongs were particularly associated with Naturalism and its perceived cheapening of literature and art:

The union between the symbolists, beyond an undeniable love of art, and a common soft spot for the unknowns of a previous age, was above all founded on a collection of rejections of former habits. Refusing the lyric and Romanesque anecdote, refusing to write according to the latest fashions, under pretext of adapting to the ignorance of the reader, rejecting the closed art of the Parnassians, and Hugo’s cult pushed to fetishism, protesting against the banality of the little naturalists, withdrawing from the gossipy novel and the overly simplistic text, renouncing minor analysis and rather attempting synthesis, taking account of foreign contributions when it was that of the great Russians or Scandinavians, progressive – such were the shared characteristics.7

Yet, likely as a result of both this reticence and the inherent eclecticism of their art, the influence of the Symbolists on mainstream art was limited and should not therefore be overstated – where it can be shown that a sort of establishment Naturalism remained preeminent in France during the period under consideration (whose Republican leanings were part of the reason certain Symbolists, for example Redon, rejected it so fiercely) – and there is no intention of doing so here.8 Many Symbolists were considered to be dandies by their contemporaries, something which, beyond the concerns of their poetry itself, may be explained by their adulation of the French aristocrat and writer Robert de Montesquieu (1855–1921), and his countryman the author Karl Joris Huysmans’ (1848–1907) idealization of him in his novel Against the Grain (1884; see Huysmans and Howard 2009). Montesquieu, transposed by Huysmans as his novel’s protagonist Des Esseintes, deliberately cultivated a sort of extreme intellectual refinement and luxuriance. Huysmans captures this aristocratic Symbolist ideal in the personality of the hero (/anti-hero) of his novel, which is itself a sort of series of digressions chapter by chapter, following Des Esseintes’ various obsessions. If these have anything in common, it is that they are all characterized by his desire to obtain a further form of refinement or experience a novel sensation. These range from everything from experimentation with deeper states of inebriation in the attempt to reach higher levels of inspiration, to more extreme forms of sexual debauchery, to an (ultimately abortive) attempt to gild an unfortunate turtle’s shell with jewels! Des Esseintes himself is characterized as a sort of aristocratic recluse, a young yet jaded man, whose senses are already dulled by the various pleasures and experiences he has had. We might speak of the ‘decadence’ of Huysmans’ protagonist. Decadence was itself a term applied somewhat more broadly during the period to reflect that pursuit of new experience and poetic and artistic styles which characterized the age. Many Symbolists were considered ‘decadents’ by their contemporaries, even if today we might not consider the two terms as exactly interchangeable. Kahn (1902: 33–4) described the distinction as follows:

In 1885, there were decadents and symbolists, many decadents and few symbolists. The word ‘decadent’ had been pronounced, but not yet that of ‘symbolist’; we were speaking of the symbol, we had not created the generic term ‘symbolism’, and thus decadents and symbolists were something different. The word ‘decadent’ had been created by journalists, some of whom had, so they said, picked it up as the beggars of Holland had the insulting epithet.9

While Des Esseintes summarizes well in his person much of the dislike the Symbolists incurred on the part of their contemporaries, there is a sense in which the author glories in his decadence, his intellectual snobbery, disdain and debauchery. And this captures an essential characteristic of Symbolism as a whole: highly intellectual, turning away from the world and its vulgarity, pursuing mystic inspiration, bucking sexual conventions in the cause of erotic experimentation – and, above all, unapologetic in doing so.

This dynamic also applied to how the Symbolists engaged with the classics. We should be clear upfront by what we mean by the term ‘the classics’ (and ‘classical’). The term may of course mean different things in different contexts, but it is used throughout this book in the sense of the collective literary, artistic and philosophical inheritance of ancient Greek and Roman civilization. Although the term may be found objectionable for its historical generality, it has been preferred in this study in the absence of a more suitable alternative as best reflecting the education and artistic conception of the Symbolists themselves, who, as previous generations of artists, most often considered the legacy of Greek and Roman antiquity collectively – even if within this they often had pronounced preferences. Huysmans captures the Symbolists’ relationship with that legacy well in the fourth chapter of his novel, which is essentially a long (and rather laborious) list of all of the Latin literature that Des Esseintes either loved or hate...