1

Retail Architecture

The Visibility of Construction and Renovation

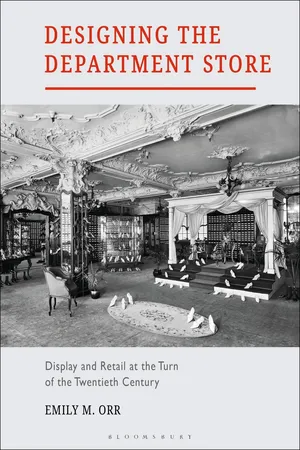

While contrasting regulations in building codes determined a number of notable divergences in the development of department store architecture in America and Britain, architects in both countries aimed to achieve a similarly symbolic yet highly functional and enticing type of building. Retail architecture emerged as a specific design practice, driven by goals of light, circulation, organization, visibility, and modernization. Architects developed the ideal plans for a building explicitly designed to accelerate the viewing and purchasing of merchandise. Windows grew, aisles widened, vistas expanded, lighting intensified, and the movement of goods and people quickened. The buildings’ impressions from the street were of utmost importance since the department store thrived on foot traffic. Even though many shared characteristics can be identified in the architecture of leading department stores in Chicago, London, and New York, stores also individually advocated for how their architecture’s particularly evocative style and efficiency set their shopping experience apart. Marshall Field’s had its Tiffany glass dome; Selfridge’s offered its visitors a ride in an elevator with bronze and cast-iron scenes of the Zodiac; Macy’s had its wooden escalator.

While architecture developed at the service of display needs, architectural milestones also provided the impetus to advertise, celebrate with new displays, and invite the public for appraisal of the new shopping space. In 1898, the London department store D. H. Evans grew with the purchase of 308 Oxford Street. An account book of that year lists that a blanket show took place to celebrate when the new shopfronts were completed on the week of October 15. A store-wide inauguration sale quickly followed on the week of October 29.1 Alignment between architectural upgrading and visual merchandising signaled the currency of the business’s identity.

Architecture was a leading component in the department store’s promotional agenda not only as a stylistic statement and a source of civic pride but also as a technological marvel. Advertisements emphasized progress and speed with stores’ building programs by comparing characteristics of the most recent iteration of a store against previous inferior facilities. For instance, an advertisement published on October 10, 1903, for the fast approaching opening of the new Schlesinger and Mayer store in the Chicago Tribune summoned the public to take the role of architectural spectators (Figure 1.1). The advertisement positioned the building, a “perfect product of architecture and building construction,” as central to the earning of “public confidence” and the enabling of the optimal shopping experience.2 The advertisement featured the rounded façade, characterized by Louis Sullivan’s cast-iron ornament at its entrance, second-floor show windows, and towering twelve stories. A group of customers at ground level appear overshadowed by the building’s magnitude, designed to impress. The advertisement invited the reader “to inspect our multiplied facilities” and included a list of “distinctive features” promoting foremost “the corner circular entrance, mahogany and marble fixtures, new combination arc and incandescent lights” and the “largest and finest display windows in the world.” This list of technological elements and luxurious stylistic attributes enumerated Schlesinger and Mayer’s commitment to a modern retail environment. The advertisement’s tag line, “In Two Days Another Great New Store,” was embedded with a message of reinvention and anticipation, promising a new retail experience soon.

The architecture of the department store facilitated a modern shopping experience via industrial and technical ingenuity, up-to-date styling, and most conspicuously, a nearly constant cycle of renovation propelled by design production and innovation. As Lewis Mumford has written, “If the vitality of an institution may be gauged by its architecture, the department store was one of the most vital institutions of the era.”3 Upon the opening of Lord & Taylor’s new building at 20th and Broadway in 1871, a New York newspaper reported, “It has been said that no one could have the best house in New York for more than a day; for, by the time it was done, somebody would be putting up a better one.”4 The world’s fair also helped to shape a new understanding of architecture as a symbolic yet temporary display feature.5 On the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition, the endurance of the Beaux Arts style was at odds with the exhibition’s limited existence, a dialectic with which the department store also contended.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, the construction sites of commerce were the grounds for real estate battles. Stores were in constant competition to expand as rapidly, efficiently, and impressively as possible. The department store’s ongoing construction process was an act of design production that featured in the department store’s advertising scheme as well as contributed to the vital qualities of the department store experience. Retail architecture therefore should not be read in isolation but instead as one element in the department store’s changeable program of display along with the show window and interior and exterior decorations.

The swelling scale of these buildings came at a price and the cost of centrally located Manhattan property rose sharply at the turn of the twentieth century; for instance, a typical 100-by-25-foot lot along Fifth Avenue cost $125,000 in 1901, $300,000 in 1906, and $350,000 to 400,000 in 1907.6 Therefore, architectural development became an increasingly strong measure of financial success over time. The expansion rate of Abraham & Straus is particularly telling of the ambitious pace at which this expansion took place. When the store first opened as a small dry goods shop in Brooklyn in 1865, its dimensions were 25 by 90 feet, the same size as the food shop alone within the larger department store of 1965.7 Abraham & Straus underwent twenty-eight expansions in its first one hundred years.8 In both America and Britain, stores illustrated their architectural expansion in advertisements to prove financial prowess and promise stylistic evolution.9 For instance, in its in-house periodical, the Harrodian Gazette, Harrods ran an illustration in 1913 with the headline “The Progress of Harrods,” showing the genealogy of the department store’s architectural history through its six buildings, up to its current home location in Knightsbridge.

Retail architecture’s construction affected urban life in a number of significant ways. As retail districts emerged, the construction of stores dramatically altered the nature of neighborhoods. Fifth Avenue experienced an incredible overhaul in the early twentieth century, transitioning from a residential district of brownstones to large lots upon which department stores B. Altman (1905–10), Bonwit Teller (1911), and Lord and Taylor (1914) stood.10 The visibility of stores’ construction processes conspicuously indicated cities’ growth in the retail sector, while also signaling to passersby the promises of new display possibilities and amenities. As the Dry Goods Economist reported in 1902, “Probably the majority of ECONOMIST readers are familiar with the exterior plans of the new Macy store, having seen it in its unfinished condition on their visits to New York.”11 At times of expansion while construction on other areas of the store was underway, stores aimed to keep as much of their selling spaces as accessible and functional as possible. These circumstances put new demands on the architectural and engineering professions, further complicating the existing technological challenges of erecting a tall, fireproof, steel-framed structure. During the building of Mandel’s department store’s major construction project in Chicago in 1912, the south section was in continuous use until the new north section could be used12 (Figure 1.2). Therefore, shopping and construction occurred side by side, making the building’s renovation a highly visible and audible element of the shopping experience.

From the perspective of the city dweller, the grandiosity of the department store represented a merging of existing cultural institutions. The New York World reported on December 19, 1886,...