![]()

1

Introduction

I.INTRODUCTION

International disputes may often reflect the opposition of fundamental values or approaches underlying international law and community. As will be discussed in this book, the South China Sea arbitration between the Republic of the Philippines (‘the Philippines’) and the People’s Republic of China (‘China’) vividly created vacillations such as: unilateralism versus multilateralism, states’ interests versus community interests, and voluntary procedure versus the compulsory procedure of international dispute settlement. Given such fundamental oppositions, we would be faced with a choice that will affect the interpretation and application of rules of international law. Thus the South China Sea arbitration provides an interesting case-study when considering an aspect of the development of international law and community.

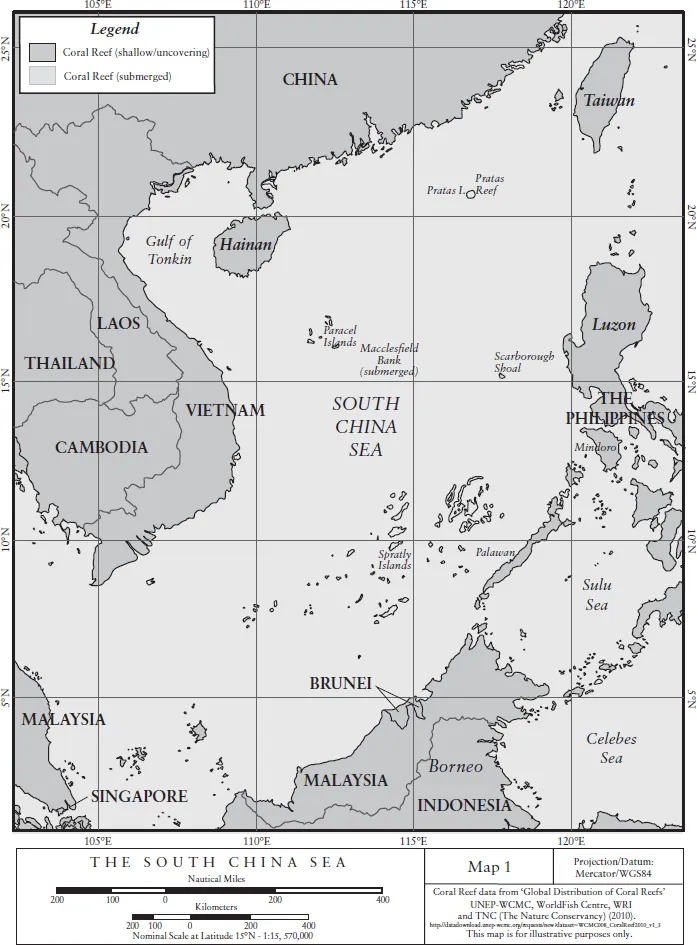

The South China Sea disputes are a complex mix, involving both territorial and maritime disputes. At present, multiple states claim territorial sovereignty over maritime features in the South China Sea.1 In particular, the Spratly Islands are the site of longstanding territorial disputes between China, Taiwan and Viet Nam. The Philippines also claims territorial sovereignty over maritime features of the Spratly Islands that fall within the Kalayaan Island Group. Malaysia claims territorial sovereignty over several maritime features, and one reef lies within 200 nautical miles of Brunei Darussalam.2 The Paracells are claimed by China, Taiwan and Viet Nam, and Scarborough Shoal is claimed by China, the Philippines and Taiwan.3 The territorial disputes are linked to various maritime disputes in the same region, such as disputes regarding: entitlement to marine spaces, maritime delimitation, fisheries, the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources in the seabed and its subsoil, navigation and marine environmental protection.4 Hence, the characterisation of the dispute is of critical importance in the South China Sea arbitration.

Figure 1.1 The South China Sea

Source: The South China Sea Arbitration Award (Merits), 9. Reproduced with permission of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (copyright holder).

The South China Sea, which covers around 3.5 million square kilometres, is a semi-enclosed sea in the western Pacific Ocean, surrounded by China, the Philippines, Viet Nam, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Indonesia (see Figure 1.1).5 It is a lifeline for oil and gas supplies from the Middle East, Africa, Australia and Southeast Asia to the large resource import-dependent countries of Northeast Asia.6 Given that international energy markets depend on reliable transport routes, the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is of critical importance.7 Furthermore, the South China Sea is one of the world’s important fishing grounds and is rich in biological diversity.8 In particular, Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands experience an extreme diversity of coastal fish and a high percentage of the living representatives of seagrasses, corals, giant clams, marine turtles and many other marine groups.9 In addition, the energy reserves under the South China Sea are attracting growing attention.10 If as much oil and gas exist in the South China Sea as is hoped, access to the potential oil and gas wealth will be crucial for the economic development of states in the region. In light of its economic, strategic and political importance, it would be no exaggeration to say that international disputes in the South China Sea may affect all countries that are linked to it.11 In this sense, the peaceful settlement of the South China Sea disputes should be regarded as a crucial issue in international relations.12

Apart from the Philippines, no states surrounding the South China Sea accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) pursuant to Article 36(2) of the Statute of the ICJ.13 While all states surrounding the South China Sea ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS or ‘the Convention’),14 no states in the region chose the dispute settlement procedure pursuant to Article 287 of the Convention. Thus the states are to be deemed to have accepted arbitration in accordance with Annex VII to the Convention in accordance with Article 287(3). It follows that, unless otherwise agreed, arbitration under Annex VII to the UNCLOS is the only compulsory procedure of international dispute settlement when a dispute cannot be resolved through diplomatic means. The Philippines thus instituted arbitral proceedings against China in accordance with the UNCLOS. The South China Sea arbitration was bifurcated and the Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal issued its Award on Jurisdiction on 29 October 2015.15 It then issued its Award on the Merits on 12 July 2016.16 The Tribunal decided all issues unanimously.

Before examination of the South China Sea Arbitration Awards,17 as a preliminary consideration, it is necessary to briefly review the course of the litigation in the South China Sea arbitration.

II.COURSE OF THE LITIGATION

According to the Philippines, under the authority of the Province of Hainan, China formally created a new administrative unit that included all of the maritime features and waters within the ‘nine-dash line’18 in June 2012. In November 2012, the provincial government of Hainan Province promulgated a law calling for the inspection, expulsion or detention of vessels ‘illegally’ entering the waters claimed by China within this area. This law went into effect on 1 January 2013.19 In response, by Notification and Statement of Claim dated 22 January 2013, the Philippines initiated arbitration proceedings against China in accordance with Articles 286 and 287 of the UNCLOS and Article 1 of Annex VII to the Convention. The Philippines, in its Notification and Statement of Claim, stressed that it

does not seek in this arbitration a determination of which Party enjoys sovereignty over the islands claimed by both of them. Nor does it request a delimitation of any maritime boundaries. The Philippines is conscious of China’s Declaration of 25 August 2006 under Article 298 of UNCLOS, and has avoided raising subjects or making claims that China has, by virtue of that Declaration, excluded from arbitral jurisdiction.20

China, in its Note Verbale to the Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines on 19 February 2013,21 rejected the arbitration and returned the Notification and Statement of Claim to the Philippines.22 In the Note Verbale of 19 February 2013, it claimed that ‘At the core of the disputes between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea are the territorial disputes over some islands and reefs of the Nansha Islands.’23 For China,

[t]he territorial disputes between China and the Philippines are still pending and unresolved, but both sides have agreed to settle the disputes through bilateral negotiations. By initiating arbitration proceedings, the Philippines runs counter to the agreement between the two countries, and also contravenes the principles and spirit of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC), and particularly ‘to resolve their territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, … through friendly consultations and negotiations by sovereign states directly concerned’.24

In the end, China chose not to appear before the Tribunal.25

In its Notification and Statement of Claim, the Philippines appointed Judge Rüdiger Wolfrum, a German national, as a member of the Tribunal in accordance with Article 3(b) of Annex VII to the UNCLOS. China did not appoint an arbitrator. Accordingly, on 23 March 2013, Judge Yanai, the President of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), appointed Judge Stanislaw Pawlak, a national of Poland, as the second arbitrator pursuant to Article 3(c) and (e) of Annex VII to the Convention. On 24 April 2013, the President of ITLOS further appointed the remaining three arbitrators in accordance with Article 3(d) and (e) of Annex VII to the Convention. They were: Judge Jean-Pierre Cot, a national of France; Professor Alfred HA Soons, a national of the Netherlands; and Ambassador MCW Pinto, a national of Sri Lanka, as arbitrator and President of the Tribunal. Since Ambassador Pinto withdrew from the Tribunal on 21 June 2013, the President of ITLOS appointed Judge Thomas A Mensah, a national of Ghana, as arbitrator and President of the Tribunal, in accordance with Articles 3(e) and (f) of Annex VII to the Convention. Thus the Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal (‘the Tribunal’) was duly constituted on 21 June 2013.26 Under Article 7(1) of the Rules of Procedure, ‘[a]ny arbitrator may be challenged if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence’. However, China did not legally challenge any arbitrator’s impartiality or independence pursuant to Article 7(1).27

In the arbitral proceedings, the Philippines presented its ‘strong interest in transparency and public access to information’, and it proposed that the verbatim records of the hearing be published after review and correction. It also urged the Tribunal to consider opening the Hearing on Jurisdiction to the public.28 While the Tribunal decided that the Registry would issue a press release at the time of the Hearing on Jurisdiction and would publish corrected transcripts shortly thereafter, it informed the Parties that the hearing would not be open to the public generally.29 On 3 July 2015, however, the Tribunal informed the Parties that it had agreed to permit each of the Governments of Malaysia, Viet Nam, Indonesia, Japan and Thailand to send small delegations of representatives to attend the hearing as observers. All observer delegations were reminded that their role would be to watch and listen, not to make statements.30 However, Viet Nam actively expressed its view with regard to substantive issues in the South China Sea arbitration.31 In addition, certain materials were made public by Taiwan.32

Pursuant to Article 31(1) of the Rules of Procedure, the expenses of the Tribunal, including the remuneration of its members, shall be borne by the Parties in equal shares. Under Article 33(1) of the Rules, the Registry may request each Party to deposit an equal amount as an advance for the expenses referred to in A...