![]()

1

Minds, gods and group selection theory

According to the standard model of the CSR, the human mind evolved modules that were adaptive to the Pleistocene conditions of our forebears, and due to the influence of these mental mechanisms, religion is possible (Lawson and McCauley 1990). That is, religious thought and accompanying behaviour are natural due to the structure of the human cognitive architecture. Yet, there is considerable debate between the different schools within the CSR, particularly when it comes to the conversation about the innateness of religious belief. For instance, Pascal Boyer argues persuasively that religious ideas are parasitic on the naturally evolved processes of the human mind, and although religious ideas are found virtually in every culture, these ideas are not inevitable (Boyer 1994). Like Boyer, Justin Barrett makes the case that religious ideas are the product of ordinary cognitive processes; however, Barrett claims that religion, particularly monotheistic religions, is not only inescapable but also, to a large extent, beneficial for humanity (Barrett 2004). Still others argue that belief in supernatural agents was biologically selected for due to their beneficial effects on cooperation (Bering and Johnson 2005; Bering 2007; Johnson 2016). Jesse Bering goes so far as to suggest that ‘God is a way of thinking that has been rendered permanent by natural selection’ (Bering 2007, p. 168). Finally, some contend, although not a biological adaptation, belief in supernatural agents or gods is a functional adaptation at the level of the group (Wilson 2002, 2015; Norenzayan 2013).

Despite the differences in the diverse methodologies in the study of religion, and consequently, the multiple interpretations derived from the data produced by the CSR researchers, they all tend to use phrases and concepts that are not entirely clear. For instance, CSR researchers repeatedly use phrases such as ‘religious thinking’, ‘religious dispositions’ and ‘religious concepts’. While these phrases lead to ambiguous claims, a more fundamental concern is how does one satisfactorily define religion? William James interpreted religion as ‘the feelings, acts and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider divine’ (James 1902, p. 34). Emile Durkheim, on the other hand, considered religion as ‘a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is things set apart and forbidden’ (Durkheim 1912, p. 44). The former emphasizes the so-called mystical experiences of individuals, while the latter stresses the importance of religious doctrines or institutions. Today, the definition of religion used by James is associated with spirituality, while the definition adopted by Durkheim describes the religious institution.

Both these terms, religion and spirituality, are so vague and refer to such a wide variety of phenomena that they are very difficult to define clearly. Traditionally, in the comparative study of religion, scholars presumed that religion was a universal phenomenon that had been interpreted differently by all cultures. It was as if there existed an objective feature of all societies that could be grasped, studied and compared. Even today, some argue, ‘for very good scientific reasons, emphasizing cross-religion similarities is the way the science of religion is typically done’ (Barrett 2004, p. 75). In contrast, I suggest that it is quite hopeless to try to identify a universal essence of religion. Sam Harris points out that attempting to find the ‘unity of religions’ is confusing and suggests that the word religions is comparable to the word sports. To suggest that sports is a universal activity does not help us in understanding what the athletes actually do. He suggests that what sports have in common, besides the fact that the participants breathe, is not very much (Harris 2014).

Furthermore, other scholars who studied religion refused to consider it as something to be explained but elevated it to a position that suggested that it was different from any other human behaviour. One influential religious studies scholar argued that ‘no statement of religion is valid unless it can be acknowledged by that religion’s believers’ (Smith 1959, p. 42). So, it was claimed that unless you were a part of the particular religion, you had no chance of understanding what it was really about. The term religion then constituted something so special that it was sacrosanct and indescribable.

The term spirituality is an even more difficult term to unpack. You may hear people say, ‘I am not very religious but I am spiritual’. What exactly does this mean? Historically, spirituality is a term that has been associated with values or morality, but seemingly not concerned with material ‘stuff’ like elaborate homes, fast cars or a fondness for dressing expensively. However, one does not necessarily have to have a belief in a supernatural world to have an awestruck vision of life, grateful for the innumerable wonders of the world and quite content with the vicissitudes of daily life. To be spiritual does not necessarily have anything to do with the supernatural or the gods. I argue that the majority of people want to live a good life, and rather than suggesting that they are spiritual, we should just simply say they are human.

Rather than concentrating on religions, the first part of this chapter aims at an explanation for the belief in gods. The reason for focusing on gods is threefold. First, as just mentioned, there are just too many problems associated with defining religion, and arguably, the idea of god is less ambiguous than the term religion. Second, it appears that most, if not all, cultures throughout history have had a belief in a supernatural world, and within this world, there were agents with ‘strategic information’ about the states of affairs in the ordinary world (Boyer 1994). Third, and most importantly, ultimately we want to determine why people are better at getting along at the level of civilizations, and the argument from many of the CSR researchers is that prosocial religions with their ‘belief in Big Gods who, watch intervene, and demand hard-to-fake loyalty displays, facilitated the rise of cooperation in large groups of anonymous strangers’ (Norenzayan 2013, p. 8). Therefore, to determine whether the idea of god or God was a good buy in the marketplace of world views, we need to establish why people could have such convictions in the first place.

This chapter will be outlined in the following manner. First, it will be argued that evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience suggests that within the human brain there are two cognitive systems that have considerably different functions. The two processes have been labelled System 1 and System 2. The former involves intuitive processes that serve the goals of the genes, while the latter is viewed as a controlled process that serves the goals of the individual. While our ideas about gods arise from our intuitive thinking, these thoughts are not held in isolation. They are shared narrative accounts of the experiences of encounters with what are believed to be supernatural agents. I will argue that the stories told about such supernatural agents and gods are influential because they are deemed to be important by the particular community. From there, I will look at the argument proposed by some researchers incorporating a so-called group selection approach in the study of religion who claim that groups made up of people who believed in god outcompeted other non-god-fearing groups. Historically, there has been controversy about the idea of group selection in evolution generally, but when it comes to its use in religion, I contend that the evidence provided is simply too weak to be taken seriously. I will begin with the dual-process theory of human cognition.

The prevailing view among many neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists is to conceive the human mind as involving two distinct sets of processes (Lieberman 2007). The automatic system is spontaneous, reflexive and involves emotions and arises early in evolution and development. The second system is controlled and is slower, takes more effort, involves declarative and reflective thinking and arises late in evolution and development. Although there is a general agreement that human cognition involves two distinct processes, there are many ways of describing it. For instance, Matthew Lieberman calls the reflexive or automatic structure the X system, while the reflective or controlled component is referred to as the C system (Lieberman 2007). Others have differentiated the two as heuristic versus analytic (Evans 2010), automatic versus conscious (Bargh and Chartrand 1999) or intuitive versus reasoning (Haidt 2001). More recently, psychologist Joshua Greene equated the dual process with a camera, equipped with both a point and shoot setting and a manual mode (Greene 2013). The automatic option on a camera is not very flexible but is highly efficient and fast, while the manual mode takes longer but gives greater flexibility.

System 1 – The autonomous set of systems

One of the pioneers for developing the dual process of cognitive functioning is Keith Stanovich, and his theory of human cognition is similar to Greene’s without the problems associated with the camera metaphor. Stanovich suggests that within the brain, there are two cognitive systems with ‘separable goal structures and separate types of mechanisms for implementing the goal structures’ (Stanovich 2004, p. 34). He appropriately calls System 1 as The Autonomous Set of Systems (TASS) as this counters any connotations of a single cognitive system. Rather than a single structure, the idea of TASS suggests a number of systems unified by the fact that they are all triggered autonomously by both internal and external stimuli and are not under the control of the analytic processing system. TASS is evolutionarily older than System 2 and was fashioned by solving the problems faced by our ancestors throughout our evolutionary history. TASS is characterized as fast, automatic, heuristic, mostly beyond awareness and effortless and serves the goals of our genes (Stanovich 2004, p. 44–45).

TASS includes encapsulated modules for solving adaptive problems in our evolutionary history, emotional regulation and ‘processes of experiential association that have been learned to automaticity’ (Stanovich and Toplah 2012, p. 8). Where this theory differs slightly from some evolutionary psychologists is in the claim that although innate modules are an essential component of TASS, they also include processes of behavioural control by the emotions and the fact that some processes are influenced by experience and practice. The important point here is that the property of autonomy can be acquired. That is, problems can be contextualized in the light of one’s prior belief and knowledge. The key features of TASS therefore include automatically responding to domain-relevant stimuli, that the execution is free from an analytic processing system and that TASS and System 2 processing are occasionally at odds (Stanovich 2004, p. 37).

TASS autonomously responds to stimuli and primes the organism to be ready. Once the stimuli are detected by one of the subsystems of TASS, they cannot be ‘turned off’ (Stanovich 2004, p. 52). TASS continuously offers suggestions to System 2 in the form of intuitions and feelings. So it is not only that TASS is generating responses on its own, but it is also providing information from both the social and physical environments in order for the analytic system to make sense of the world. When the two systems are at odds, we typically default to System 1 processing as it takes less computational effort. Humans therefore are, at times, ‘cognitive misers’ (Stanovich 2011, p. 30).

System 2 – processing

In contrast to the operating system of TASS, System 2 processing is characterized as slow, controlled by a central executive, effortful, under conscious awareness, rule-based and serves the goals of the individual (Stanovich 2004). TASS feeds System 2 with information about the social and physical world, and from that information, System 2 fosters a coherent story. One of the key features of System 2 is the ability for hypothetical reasoning. Hypothetical reasoning allows the individual to postulate different conceivable scenarios about the state of the world, and this acumen is required for such behaviours as deductive reasoning, decision-making and scientific thinking: the mind tools necessary for rational thought.

A good example of System 2 reasoning can be demonstrated by a brain-teaser, sometimes referred to as the Ann problem. Consider the following information. Jack is looking at Ann, but Ann is looking at George. Jack is married, but George is not. The question posed is whether a married person is looking at an unmarried person. One can respond with either yes, no or cannot tell. Over 80 per cent of the people who participated responded by indicating that they could not tell, which is incorrect as the correct answer is yes (Stanovich 2015).

The riddle can be solved by using disjunctive reasoning, that is, reasoning that includes all the possibilities. Since we do not know whether Ann is married or not, but we do know the marital status of the two men, we need to think this through by looking at the question with the possibility that Ann is married and with the plausibility that Ann is not married. By using this method of thinking, we surmise if Ann is married, then a married person (Ann) is looking at an unmarried person (George). Alternatively, if Ann is not married, then a married person (Jack) is looking at an unmarried person (Ann). From this, we have determined, yes indeed a married person is looking at an unmarried person. Clearly, this type of reasoning is slow, certainly under conscious awareness, rule-based and demanding in the sense that one must simultaneously hold separate hypotheticals in mind and therefore requires a working memory.

Many of the dual-system accounts divide the two ways of thinking; however, Stanovich takes it one step further and suggests that System 2-type thinking should be distinguished between the algorithmic and reflective mind. He defends this position effectively by pointing out the extensive literature on individual differences between cognitive ability and thinking dispositions (Stanovich 2011). He provides evidence by identifying the mass of cognitive biases that have little to do with cognitive ability (Stanovich 2011). For Stanovich, this is quite evident when studying intelligence tests, as these assessments only capture the algorithmic ability and not the ability of the reflective mind. That is why smart people make common mistakes.

It has been argued that one of the main functions of System 2 is to override TASS. The problem with much of the literature on thinking biases erroneously assumed that System 2 processing failed to override our TASS impulses. Stanovich suggests that if System 2 was never called upon in the first place, then it should not be considered an override problem. To help articulate how to explain override problems in System 2, he uses David Perkins’ terminology of mindware. By mindware, he means probabilistic reasoning, scientific reasoning, falsification and causal reasoning. One learns these types of reasoning from experience; however, if one does not have the information or rule, then one would not have the ability to reflect on alternative views. Stanovich concludes that the first default in System 2 is to employ a serial associative cognition with a focal bias. By this he means that the individual fails to fully develop a mental simulation. A good example of serial associative cognition with a focal bias is captured in studies using the Wason Four Card Selection Task (Figure 1).

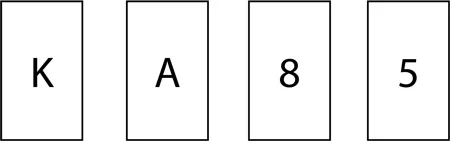

Figure 1 Wason Four Card Selection Task.

Participants are shown four cards as illustrated below. They are told that each card has a number on one side and a letter on the reverse. The rule simply states that when a card is shown with a vowel on one side, then there will be an even number on the opposite side. The participants must determine what card(s) must be turned over in order to determine whether the rule is true or false. To arrive at the correct answer, the participant must turn over two cards, A and 5. The majority of participants, however, select A and 8. In interpreting the results from these types of tasks, Jonathan Evans has called attention to the fact that researchers have incorrectly concluded that there is no Type 2 processing involved but only Type 1 processing (Evans 2008).

By analysing the results of these studies, Stanovich found that most of the subjects were engaged in slow, methodical processing. Problems occurred, however, when subjects failed to consider any other possibilities. The majority of subjects did not hypothesize a situation where the rule could be false. Indeed Wason was interested in determining whether people were good at falsifying hypotheses. Stanovich suggests that the problem lies with the fact that participants assume the rule true and then worked through what would happen only if the rule was true. To arrive at their answer, the subjects were not using automatic processing but were nonetheless ‘inflexibly locked into an associative mode that takes as its starting point the model of the world, that is the one most easy to construct’ (Stanovich 2011, p. 65). The individual begins with a focal model and never considers deviating from it but simply generates associations, failing to generate an alternative hypothesis. Reasoning in this way leads people to ‘represent only one state of affairs’ (Stanovich 2011, p. 66). Instead of considering all possible alternatives, subjects in the Wason Four Card Selection Task start with the given rule and then attempt to confirm their assumption.

How this assists us with understanding the persistence of belief in gods is the fact that TASS processing gives us the potential to conceive of gods and other supernatural agents, and our algorithmic mind creates and circulates the stories told about these beliefs. However, a reflective mind involves falsification and scientific reasoning, mind tools that are not always used to assess the rationality of the stories about the gods. I will argue that in addition to having a reflective mind, a necessary condition for reflective thinking is an environment where this type of reasoning is permitted and, more importantly, encouraged. Later in this chapter, I will argue that we find evidence for the necessary environment for free thought and reflective thinking with the Milesians, a group of freethinkers from the sixth century BCE. First, however, the relationship between TASS and God concepts will be discussed presently.

TASS and God concepts

CSR researchers have identified a number of TASS system modules to account for the ubiquitous belief in supernatural agents or gods. They suggest that much of our thinking about gods arises from interpreting the world through TASS. Justin Barrett doesn’t use the same wording, but he clearly separates beliefs into reflective and non-reflective, with the former being held consciously arising through deliberate reflection, while the latter comes automatically and seems to arise instantaneously. Barrett suggests that ‘our minds produce non-reflective beliefs automatically, all the time’ (Barrett 2004, p. 181). What influences our beliefs, including what we think exists in the world, arises from mental tools that dwell below our conscious radar (Boyer 2001, p. 107). For Boyer, ‘when creating what might be called reflective beliefs, unless given strong reason to the contrary, we simply adopt these non-reflective beliefs as reflective beliefs’ (Boyer 2001, p. 107).

The reason for the belief in gods, suggested by these theorists, is simply due to the fact that such belief is supported by our intuitive mind tools. How we come to think about the characteristics of the gods attractively fit with what people understand about the nature of the world. People are outfitted with innate intuitive theories about how the world works. In fact, it seems that how humans acquire knowledge about anything is influenced by our predisposed intuitions in the separate domains of physics, biology and psychology. For instance, within the physical domain, children have intuitive knowledge about the characteristics of objects. They have a sense of solidity, gravity and movement. Research suggests that children at a very early age would be surprised to find objects jumping over or passing through other objects or surfaces (Spelke 1994). Additionally, children intuitively believe that objects can only act upon another object if they come into contact with each other (Spelke 1994). Finally, children who are put in front of a flight simulator and tasked to bomb a target on the ground tend to miss the mark. Intuitively, children wait until they are over the target, failing to consider that when the bomb is dropped, it will continue forward at the pace of the aircraft, drastically affecting where it will land. This has also bee...