![]()

1

War: Comic, Tragic and Nostalgic

The Brits are proud of their military might. Britain has a warlike history, and audiences have always loved plays about soldiers. In particular they love stories about the Second World War, which offer an easy patriotism, allowing spectators to feel part of a nation’s military effort, even if vicariously. In genre terms, a typical military play is a comedy about a group of ordinary soldiers – whether in the army, navy or air force – from different civilian backgrounds. They are mainly young, with one or two older hands. Each man is an individual and each represents a slightly different class, region or social type, the idea being that together they symbolize the whole nation. Cockney characters are common, as are Scots, Welshmen and Northerners. The story is usually set in a confined space such as a barracks or other living quarters, and shows how the men are oppressed by authority figures, who are usually spineless bullies or pettifogging bureaucrats. The injustice the men suffer is clear, and their resistance to authority is often the source of comedy. Frequently, another senior figure, an upper-class officer, has to intervene to restore order, and to see that justice is done. Women are either harridans or flirts – and always secondary to the men. For war is a man’s business. At least, that is the myth.

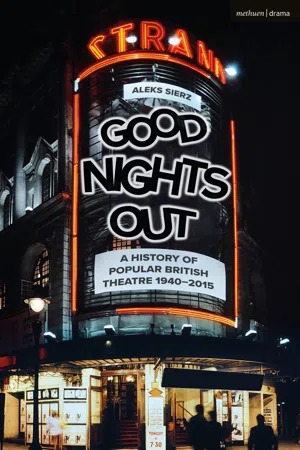

At the outbreak of the Second World War, theatre critic J. C. Trewin noted that ‘London demanded light entertainment’.1 Audiences craved colourful spectacle, such as the musicals of Ivor Novello, as a distraction from more serious matters. The Times review of his mega-hit Perchance To Dream (Hippodrome, 1945) said: ‘The Ivor Novello show is by this time as familiar and almost as sure of popular favour as pantomime’, offering ‘a succession of glamorous spectacles’.2 But the most popular type of wartime entertainment was light comedy; laughter, as much as visual delight, being an escape from the cares of total war. Comedies did well, but only a handful – Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit (Piccadilly, 1941), Esther McCracken’s Quiet Week-End (Wyndham’s, 1941), Joseph Kesselring’s Arsenic and Old Lace (Strand, 1942) and Terence Rattigan’s While the Sun Shines (Globe, 1943) – enjoyed more than 1,000 performances. The disruptions of war, with the call-up and the blackout, adversely affected the runs of shows, but it didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of either audiences or of amateurs. It is estimated that there were a million amateur actors in Britain in the 1940s.3 In the metropolis, comedies did their work. For example, Vivian Tidmarsh’s Is Your Honeymoon Really Necessary? (Duke of York’s, 1944), which managed 980 performances, led one audience member to record their verdict: ‘Damn silly, but a good night out.’4 Yet it was only when the conflict was over that plays about the war became really popular.

War or no war, this was the era of the service comedy and the play about military life. The key figure was producer Hugh Binkie Beaumont, head of H. M. Tennent Ltd, who dominated the West End with his conservative ideals of good taste and artistic excellence. He had a good war. Later on, looking back, he was frank about it: ‘It may sound cynical, but the war has been the making of me. Can’t complain about a thing. Look at me and look at the Firm. And to think that I owe it all to Hitler.’5 He had a point: during the war, he had presented fifty-nine plays in the West End, with only five failures. Two playwrights in particular were Beaumont’s box-office magic: Noël Coward and Terence Rattigan. And they exemplify two different ways of reacting to the wartime situation: the oblique and the direct.

Coward took an oblique approach: his comedy Blithe Spirit opened at the Piccadilly Theatre in July 1941 and ran for 1,997 performances. Written in five days during the Blitz, it was easily the most popular play of the war. Coward was typically ironic about the problems of opening a show in wartime conditions: ‘The audience, socially impeccable from the journalistic point of view and mostly in uniform, had to walk across planks laid over the rubble caused by a recent air raid to see a light comedy about death.’6 Like most wartime fare, this comedy avoided the subject of actual fighting, and instead offered a witty entertainment. The plot concerns Charles Condomine, a novelist who invites the eccentric Madame Arcati to hold a séance. She inadvertently summons the ghost of Elvira, Charles’s first wife, who plays merry havoc with Ruth, his second spouse. Although it was a distraction from the serious issues of the day, one reason that audiences liked it was that it indirectly addressed feelings of wartime loss and the desire to be reunited with people who’d died. With its moments of farcical fun, it was also very entertaining. While the story is a familiar love triangle, albeit ghostly, Arcati is a fairy-tale crone, a spirit medium both archetypal and comic, and her supernatural powers give the play its zing. Clearly, Coward’s subtext about avoiding long-term emotional commitment chimed with audiences who appreciated the fragility of any long-term planning during war, but it also radiated an image of a witty, classy and rich lifestyle which made people feel that being British was the best thing in the world.7

While the Sun Shines (1943)

If Coward was the suave court jester of British theatre, then Rattigan at his most serious was its agony aunt. But he also had a comic side, and this proved much more commercially successful than his other work. Although less of a hit than the Master’s Blithe Spirit, Rattigan’s wartime comedy While the Sun Shines was a popular show which notched up 1,154 performances. This means that Rattigan’s most commercially successful play is perhaps his least well-known. It was also the one that Beaumont, with his instinct for what the public wanted, most ardently desired. Having staged Rattigan’s breakthrough mega-hit, French Without Tears, in 1936, he kept pestering the playwright for more of the same.8 Rattigan, however, was petrified of being seen as just a one-hit wonder. And he also wanted to shake off his image of being a purveyor of trivial comedy. Before he pleased Beaumont, he had to please himself – by writing at least one serious drama.

This was Flare Path (Apollo, 1942), Rattigan’s second most popular wartime play, and one which exemplifies the stiff-upper-lip qualities of British wartime pluck.9 It tells the tangled love story of a serving RAF pilot, his actress wife and her former lover, now a film star, and features a notable scene in which the pilot realistically confesses to sometimes feeling afraid. ‘Do you know what’s the matter with me? Funk’ (66). And then he elaborates: ‘You don’t know what it’s like to feel frightened. You get a beastly, bitter taste in the mouth, and your tongue goes dry and you feel sick’ (68). Such truthful confessions upset the top brass of the air force, who were determined to preserve an image of cool heroic courage, but the general effect of Rattigan’s writing conveys both realistic emotions and a sense of stoicism. The atmosphere of common purpose in adversity includes brief moments of anti-authoritarian sentiment: ‘I hate all this patriotic bilge in the newspapers’ (53). Stoic, bolshy and realistic: these are characteristics that British audiences instantly recognized. When Winston Churchill, on a rare visit to the theatre, saw the play, he told the cast afterwards: ‘It is a masterpiece of understatement. But we are rather good at that, aren’t we?’10

Flare Path was a wartime hit, opening in August 1942 and running for eighteen months, but nothing like as popular as Coward’s comedy. Yet it did strike a chord with audiences. An unsigned review in The Times said that ‘a play on the subject of bomber pilots and of the women who wait for them to return from their raids can hardly fail to move a London audience today’.11 In The Sunday Times the veteran critic James Agate asked whether wartime dramatists were justified in using the conflict as subject matter for entertainment, and concluded that serious plays about war had the power to ‘jolt us out of our escapist rut’. He described Flare Path as ‘extraordinarily lively. A laugh every minute, a roar every five minutes, and a tear in every ten.’12 In other words, it was an emotional experience not a literary one. Like Blithe Spirit, there is a love triangle at the play’s heart – and this not only touched a chord of archetypal psychology, but also reflected the emotional complications of people’s experience of love in wartime. To underline the seriousness of the situation in 1942, the theatre programme prints an air raid warning: ‘Patrons are advised to remain in the Theatre, but those wishing to leave will be directed to the nearest official air raid shelter.’13 Stoicism was required offstage as well as on.

By contrast with this essentially serious drama, While the Sun Shines is a slick romantic comedy of wartime entanglements: set in the Albany, the posh Piccadilly apartment of an English Earl, the hay being made in this case involves three young men chasing the same woman. The dialogues are witty, in the style of French Without Tears, and the characters familiar: Bobby the Earl is a refugee from P. G. Wodehouse, his fiancée Lady Elizabeth is a naïve English rose from an aristocratic family, while her father, the Duke of Ayr and Stirling, is the blustering Tory whose wartime job is liaising with the Polish army. Bobby’s rivals are the big, brash American Joe and the passionate Frenchman Colbert, while Mabel Crum, Bobby’s other woman, is a goodtime girl. The play’s bright comedy reflected the social conditions of wartime London, its mixture of lightly stereotypical nationalities and the class consciousness of the characters: some of the laughs come from the fact that the young aristocrats are military failures while the lower-class characters are successfully climbing up through the ranks.14 At the same time, the story was popular because it reflected once again the emotional and sexual tangles that many British people experienced during the long wartime years.

Unlike Flare Path, While the Sun Shines is a comedy that stresses not the ennobling determination to grin and bear it, but the petty stupidities of wartime.15 Judging by the play’s success this was what London audiences wanted: to dream of muddling through rather than being heroic, and enjoying the chance of sexual adventure during a national emergency. Casual pick-ups during the blackout, whether homosexual or heterosexual, were a fact of life, and the play opens with a man sharing a bed with another man, albeit offstage. (By Act III, three men are sharing one bed!) This rather sly joke about gay life was subtle enough to escape the censor, but the liberal-minded Rattig...