![]()

1

School Improvement Networks in a Market-Oriented Educational Context

International evidence shows that numerous educational systems have opted for school networks to support the improvement not only of those schools in difficulty but also the system as a whole (Azorín & Muijs, 2017; Chapman, 2015; Feys & Devos, 2015; Rincón-Gallardo & Fullan, 2016). In the global north, these network initiatives are supported by methodologies of data gathering and analysis to improve practices, involving many schools, teachers and/or school leaders. Many school networks with different purposes where developed in the 1990s to address diverse educational challenges (Hadfield & Chapman, 2009). Some of these experiences focused on supporting good professional relationships among teachers, while others used networks for professional from different schools, not only teachers, to address similar educational challenges (Bryk et al., 2010; Lieberman & Grolnick, 1996; Little, 1993; Wohlstetter, Malloy, Chau, & Polhemus, 2003).

Current examples of school networks have focused their endeavor in supporting the professional capacities of principals and teachers to inquiry and enhance student learning. In Scotland, Chapman et al. (2016b) studied the School Improvement Partnership Programme (SIPP), a three-year collaborative and inquiry-driven initiative of eight networks distributed in 14 districts supported by the Robert Owen Center for Educational Change, which was designed to improve educational experiences and outcomes of children from disadvantaged backgrounds and thus contribute to closing the attainment gap in Scotland. Also, Brown and Flood (2019) describe and analyze the experience of Research Learning Networks (RLN) in England, focused in generating research-informed practices in a series of workshop with 14 networks, comprising 110 staff from 55 schools.

There are also examples of similar networks in Australia, Austria, Belgium and Spain, many of them including data gathering and analysis to improve teachers practices and support the development of leadership capacities of principals, curriculum coordinators and teachers (Azorín & Muijs, 2017; Feys & Devos, 2015; Matthews, Moorman, & Nusche 2008; Stoll, Moorman, & Rahm, 2008). Broadly, all of these networking initiatives can be described as Professional Learning Networks (PLNs).

In contrast, fewer examples of these networks can be found in Latin America, although those that do exist offer interesting insights. For instance, there are networking initiatives similar to PLNs, such as the Learning Community Project in Mexico and Escuela Nueva in Colombia. These examples share the fact that both have evolved from previous grassroots movements into official national programs. Their focus is on empowering students to guide their own learning, supporting innovative pedagogical practices between teachers and students, nurturing horizontal relationship of dialogue, co-learning and mutual influence between students, teachers and leaders (Rincón-Gallardo, 2019).

The case of Chile offers a very different picture, as it is possible to find network initiatives dating back over 30 years. A well-known example is MECE RURAL, a national program focused on improving rural education by creating networks called “Microcentros Rurales” (rural micro-centers), which bring together teachers from several small rural schools. This program has been running since 1992, and it aims to improve teachers’ practices and support collaborative professional relations (Avalos, 1999; Moreno, 2007). Similarly, municipal departments of education have traditionally formed and supported thematic networks among public municipal schools focused on Early Childhood Education, English as a Second Language, Spanish Language and Mathematics (Fuentealba & Galaz, 2008). Also, some networks specifically focus on the professional development of teachers, such as the Teachers of Teachers Network (Montecinos, Pino, Campos, Domínguez, & Carreño, 2014), and others that connect teachers with university academics, such as the network for the transformation and improvement of science education (González-Weil, Cortéz, Pérez, Bravo, & Ibaceta, 2013).

More recently, networking has been positioned as one of the core principles of a significant reform to the public education system in Chile. This reform, represented by Law No. 21.040, changes the governance structure for the provision of public education in Chile. Starting in 2018, municipal schools began to be transferred to the first four Local Public Education Services, and this process will continue over a period of 10 years (Bellei, 2018). By 2028, the 345 municipal departments of education should be reorganized into 70 Local Public Education Services, which will operate as networks to guarantee access to quality education with equity in their territory.

In addition to these public initiatives, there are several experiences led by private-subsidized foundations running state-funded schools that have developed networking as a way to efficiently administrate resources, implement educational programs and promote innovation. Some well-known examples are Belén Educa foundation with 12 schools and 18 years of existence, the Sociedad de Instrucción Primaria that has been organized as a network since 2001 with 19 schools, the Network of Leading Schools sponsored by Fundación Chile since 2007 with 110 schools, the Fundación Oportunidad working with 28 early years’ centers since 2007 applying the A Good Start program, and the Red La Salle Chile operating with seven schools as a network since the 1980s (DEP, 2018).

Among these experiences, the most recent school network initiative is the School Improvement Network (SIN) strategy, which was launched nationwide in 2015. That year, nearly 500 networks across all 15 regions of the country were created to support the improvement of municipal schools and, in some cases, private-subsidized schools.

The long tradition of school networks, the new administration of public education by the creation of the Local Public Education Services, the private-subsidized foundation projects and the nationwide SIN strategy reflect the significance of school networks for Chile. Nevertheless, there is scarce research about how networks function and even less evidence about the conditions to successfully operate in a market-oriented educational system.

A REFORM TO STRENGHTEN PUBLIC EDUCATION IN A MARKET-ORIENTED SYSTEM

Chile has been characterized as one of the first countries in the world to implement a set of neoliberal policies. Called the “neoliberal experiment”, the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973–1989) began to impose these policies, which were subsequently developed and updated by a center-left coalition of parties, during the democratic governments (1990–2010) (Bellei, 2015; Harvey, 2007; OECD, 2004; Taylor, 2006). This neoliberal perspective proposes that the organization and the management of education systems follow the same logic of markets. Schools must compete for students, and if this service is not of quality, then they will lose their customers and close (Peirano & Vargas, 2005). Lubienski and Lubienski (2014) point out that those who support the market as a way of organizing public education do so with the promise of increased effectiveness and efficiency to establish a direct link with consumers, who will choose the best education for their children, without having to go through bureaucrats or education experts that intervene with the power of their own decisions.

Two key educational policies reflect the market-oriented model of the Chilean educational system. First, a voucher system based on student enrollment and attendance to finance the educational system; if schools have low enrollment, then the administrator of that school has less resources to support the education that they provide. Second, a national standardized test (SIMCE) for high-stakes accountability purposes. These policies are connected and together foster a business capital model (Shirley, 2016). The idea is that schools will compete against each other to secure students’ enrollment in order to have the necessary resources to enable them to subsist, while SIMCE results are expected to inform families’ choice of schools for their children (Bellei & Vanni, 2015; Pino-Yancovic, 2015).

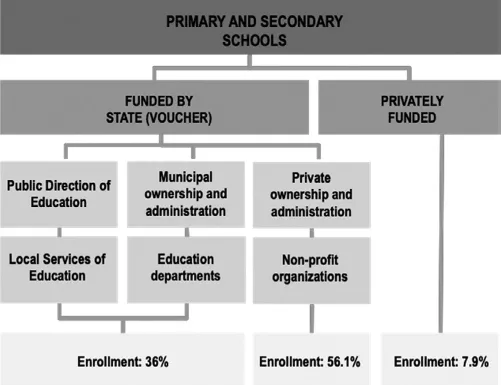

In addition, during the dictatorship, the administration of public primary and secondary schools was transferred to municipalities and private entities who received state funding through the voucher system. Until this day, municipalities run public schools through municipal departments of educational administration and are legally represented by the mayor of the municipality (Peirano & Vargas, 2005). Alternatively, some municipalities chose to devolve the administration of schools to a municipal corporation, but due to the high cost of this alternative, most municipalities opted for creating departments of educational administration (Taylor, 2006). As for private entities, they included individuals, companies and/or corporations, either for-profit or non-profit, who were authorized by the Ministry of Education to administer and run one or several schools. For two decades, private-subsidized schools could charge tuition to parents in addition to the state funds received through the voucher.

These policies have had negative consequences for the quality and equity in the education system (Valenzuela, Bellei, & De los Ríos, 2014), which led to massive social discontent demanding radical change (Bellei & Cabalin, 2013). As mentioned before, between 2014 and 2017, Chile started a process of comprehensive reform that has progressively transformed some of these policies from the dictatorship era (Valenzuela & Montecinos, 2017). One of the most important changes was the Inclusion Law, a policy that regulates school admissions, aimed to allow parents to choose and access educational institutions regardless of their economic capacity and to prevent publicly funded schools from profit seeking. Addtionally, the law that creates a New System of Public Education, which changes the governance of public education by effectively replacing the municipal administration of schools with 70 Local Public Education Services. The declared objective of this set of reforms was to ensure education as a social right, and that public education becomes accessible to every child and young person, where all students will be able to experience an integral quality learning process. Despite this explicit support for public education, some key elements of the market-oriented model of education, that might be more difficult to change, such as the voucher based on pupil attendance and the high-stakes accountability system, were not included in the reform. Fig. 1 represents the administration and enrollment share of the Chilean educational system in this reform and transition period.

Fig. 1. Administration and Enrollment Share of Chilean Educational System.

CHILE’S EDUCATIONAL IMPROVEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK

Educational improvement is currently framed by various legal and policy instruments. One very relevant is the Law No. 20.501 that created the Preferential School Subsidy. This law provides additional resources to schools with a high proportion of students from low-income families and different levels of autonomy. Schools can use those resources to define and implement their own improvement strategies, contingent to their performance. As a result, the Preferential School Subsidy formally introduced for the first time a system of rewards and sanctions based on schools’ performance measured by pupils’ attainment in the national standardized test, SIMCE, and especially those students considered socially disadvantaged (Valenzuela & Montecinos, 2017).

Another very important policy is the National System for the Quality Assurance of Education, defined by the Law No. 20.529. This new system reorganized the role of the Ministry of Education and the National Council of Education and created two new institutions to assess, guide and support the performance of individual schools: The Education Quality Agency and the Superintendence of Education. Fig. 2 represents the current organization of this system.

The Quality Agency has been instrumental in maintaining and strengthening the high-stakes individual accountability system in Chile, as it is in charge of evaluating schools’ performance based on their pupils’ outcomes in SIMCE. This performance evaluation results in the sorting and classification of schools in four levels: high, medium, medium-low, or insufficient. Schools that are classified as insufficient receive an inspection visit to evaluate their pedagogical and management processes and receive guidance and support from the Quality Agency and the Ministry of Education; however, the law establishes that if these schools are classified as insufficient for four consecutive years, they can be closed by the Ministry of Education, facing very challenging internal and external circumstances (Bellei & Vanni, 2015).

This legal and policy framework indicates that schools are responsible for leading their improvement process through the design and implementation of an Educational Improvement Plan (PME). According to the Ministry of Education, the PME is a tool “to guide, plan and materialize processes of institutional and pedagogical improvement of each educational community and for the integral development of its students” (MINEDUC, 2017b). PMEs are central component to promote insti...