![]()

ONE

Being-on-the-Mountains

ON MY FIRST VISIT TO “THE REGION,”1 I travel from Diyarbakır to Bingöl in a minibus with a Kurdish anthropologist friend who introduces me to the geography of war. As our minibus ascends the snake-like mountain roads, our trip is frequently interrupted by military checkpoints. Every so often, my friend points out a crack in the mountain walls to show me the mark left by a rocket-propelled grenade or gestures to a now barren hill once covered with oak trees to recount how the Region’s forests were burned down in an effort to destroy guerrilla hideouts. Here, violently inscribed mountains function as mnemonic artifacts that store “repertoires of historical narrative and collective action.”2

Gabar, Cudi, Kato, İkiyaka, Buzul—these are the names of mountains located in the Region that have become familiar to any regular follower of Turkish news since the 1990s. Frequently referred to as having “the most inhospitable terrain in the world,”3 these mountains are where the dialectics of guerrilla-counterguerrilla warfare takes place—where the soldiers of the Turkish Army, the paramilitary village guards,4 and the guerrillas of the PKK engage daily in a deadly hide-and-seek game. These mountains form the spatial and chimerical contours of the uncanny geography of war, formed through historically sedimented practices of violence, terror, and resistance.

As in other countries, the mountainous regions of Turkey have long been the stronghold of those wishing to escape or defy the centralizing and regulating practices and violence of the state: outlaws in hiding, social bandits challenging corrupt local authorities,5 nomadic tribes resisting the forced settlement policies of the Ottoman Empire, smugglers violating physical and economic borders, Marxist guerrillas struggling to topple the state. The mountains possess a mythical charm in popular memory through their place in local oral epic koçaklama poetry as the last bastion of those facing down injustice, sloganized in the verses of the nineteenth-century folk poet Dadaloğlu: “If the law belongs to the sultan, the mountains belong to us.” This epic tradition has been celebrated as the authentic core of Turkish national culture by the republic, which construed itself as a radical break with the Ottoman Empire. But it has also inspired the folk music of the revolutionary Left, such as Ahmet Kaya’s Şarkılarım Dağlara (My Songs to the Mountains), Turkey’s all-time best-selling album.

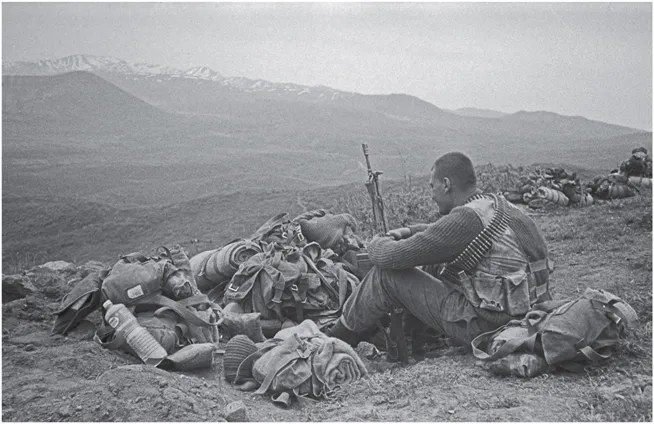

A conscript resting in the mountains, 1993. Credit: Depo Photos.

The symbolism and cultural meanings of the Region’s mountains have followed a historical trajectory that differs starkly from that of the now tamed and touristic mountains in other parts of Turkey.6 Since the foundation of the republic, the modernist discourse of Turkish nationalism has constructed the mountainous topography of the Region as the source of its historical alterity.7 In this figurative discourse, the backwardness of the Region, articulated in the tropes of tribal organization, feudalism, and customary law, is linked to the Region’s precipitous and impenetrable nature.8 In this way, the mountains here are viewed as material forces that generate and sustain difference, above all claims to ethnic difference. The state’s radical denial of the Kurds’ existence as an ethnic group until 1991 was legitimated on the grounds that Kurds were in reality Turks who had been alienated from their own ethnic identity by their isolation from the rest of the country, the dispersion of local populations into scattered settlements, and transportation difficulties. This official historical narrative goes so far as to attribute the origin of the word Kurd to the sound that Kurds’ boots make while walking on the snowy mountains: kart, kurt. Pejoratively dubbed “mountain Turks,” Kurds became Turks whose identity had been lost or—to put it more geographically—stolen by the mountains.

While Turkish nationalism blanketed the Region’s mountains in an aura of negativity, Kurdish nationalist discourse celebrated the mountains as the only reliable source of refuge in a hostile and politically volatile environment. Hence the saying in Kurdish political folklore, “Kurds have no friends but the mountains.” Sacralized in the poetics of national struggle, mountains are the privileged sites of Kurdish political memory, which accumulates sedimentary layers of resistance and martyrdom.9 In the first published eyewitness account of guerrilla life on the mountains10 and in Kurdish guerrilla memoirs,11 the border between mountains and plains is constantly recoded as the border between life and death, dignity and submission, good death and bad death. “The plains mean destruction for the guerrilla,” guerrillas say, adding, “But no one can dislodge us from these mountains.”12

From the foundation of the Turkish Republic in 1923 through to the 1990s, the Region’s mountains remained an alien presence within Turkish national geography, serving to mark the de facto boundaries of state sovereignty. In the first decades of the republic and with more urgency during the Kurdish rebellions of the 1920s and ’30s, the only acts of sovereignty targeting the mountains were bombing and naming. In an attempt to dissociate meanings from the fabric of social space and thereby erase local memories, the state gradually replaced Kurdish place-names with novel Turkish ones so as to make these places its own. Periodically, the state would supplement these mountain renaming drives with aerial bombing campaigns designed to expunge the Kurdish rebels from the newly Turkified mountains.13 Taking a bird’s-eye perspective, this nationalist gaze at the mountains registered its geography from a distance and with a sense of mastery. But this gaze also carried the anxiety of a lack created by the elusive materiality of mountains that were beyond the reach of soldiers who for several months each winter had to return to their barracks at night and remain locked there.

After the introduction of counterguerrilla warfare techniques in the early 1990s, the social geography and ecology of the mountains and the nationalist imaginary’s relation to them changed. Through a constellation of anatomopolitical14 and necropolitical15 techniques that I examine in the following section, a new soldier-body/sensorium and a new army were created in the mirror image of the guerrilla and the PKK. Soldiers began living on the mountains day and night, sometimes uninterruptedly for months. Military units were altimetrically reorganized in accordance with a dominant/subordinate location dichotomy that referred to higher (safe) and lower (unsafe) ground, respectively. With the exception of those villages converted to paramilitary village guard posts, all regional villages remote from heavily populated areas were evacuated. The Region’s mountains became preeminent spaces for inscribing the nationalist fantasy of the omnipresent Turkish state; not a single piece of land within the borders of the motherland existed beyond the reach of “the hand of the state.”16

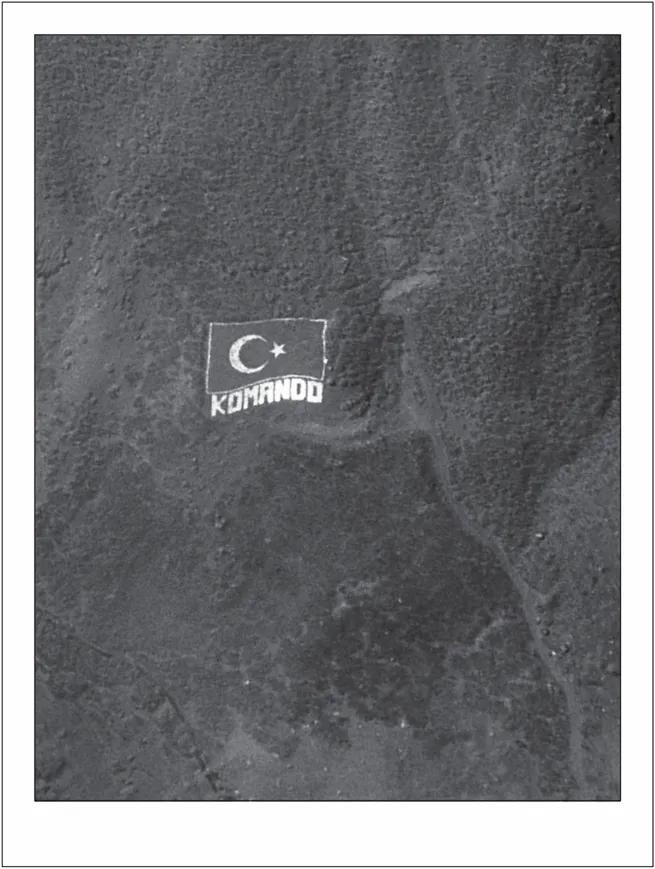

Satellite image showing spatial inscription of sovereign violence in Şemdinli, Hakkari. “Sceneries” Series—Duratrans Digital Prints, 2013. Photo courtesy of Hakan Topal.

The spatial doctrine of counterguerrilla warfare has radically transformed soldiers’ experience of being-on-the-mountains,17 as well as the meanings and emotional tones attached to the Region’s mountains. As their status within the Manichaean nationalist metaphysics of place has shifted—from demonized spaces to sites of an antagonistic copresence of soldiers and guerrillas—these mountains have become incorporated into the nationalist imaginary as enchanted sites of heroism, adventure, and martyrdom. In twenty-first-century Turkey, this fascination with the mountains has made its mark on the output of cultural products that circulate widely among an emergent nationalist public—films, poems, songs, soldiers’ photos and diaries, ex–military officers’ memoirs, and the personal videos of former recruits on the Internet abound with representations of mountains.18 The most striking feature of this new nationalist fascination with the mountains is the mimetic assimilation into the nationalist discourse of those aesthetic, emotional, and narrative structures previously associated with leftist and Kurdish struggles. Through this assimilation, the mountains are recast in the nationalist imaginary as objects of reverence, sites of redemption, silent witnesses of sacrifice, and tombs of heroic fighters “who go to their deaths as though they are going to their nuptial nights.”19 Yet old nationalist anxieties regarding the “loyalty” of these mountains to the nation have not vanished. On the contrary, they are deeply embedded in the nationalist glorification of the mountains; it is the coexistence of contesting discourses and emotional moods and regular shifts of rhetoric and tone that gives the nationalist veneration of the mountains its peculiar character.

On nationalist websites one can find tawdry, sentimentalist mountain poems in the hundreds illustrating these ambivalences. In a typical poem, titled “Mount Gabar, Mount Cudi,” the author fuses two different images of the mountains as abominable abettors and beloved partners so as to enact the slippery structures of Turkish nationalist feeling toward them.20 The poem evokes gory images of dark peaks shrouded in blood or rivers of blood to describe the murderous nature of the Region’s peaks. Then, with an unexpected emotional twist, the stanzas hit an apologetic note as the poet sympathetically cries out to the mountains, “I don’t reproach you, but understand my affliction!” Most of these poems indulge in such hyperbolic tonal twists as the mountains are made to vacillate wildly between sacred and profane domains. Their nationalist authors blame soldiers’ deaths on mountains that hide and harbor enemies, but they cannot help but venerate these places of soldiers’ deaths; death has rendered them sacred and transformed them into sites and material witnesses of martyrdom.

This nationalist ambivalence toward the Region’s mountains both structures and is structured by soldiers’ being-on-the-mountains. It also characterizes my interlocutors’ personal and public recollections of their military days in the Region. In disabled veterans’ narratives, these mountains are simultaneously sublime and monstrous, objects of awe and contempt, spaces to redeem and to conquer. During my fieldwork, I frequently heard statements like “Gabar is a cursed mountain; its soil smells of blood, its rivers flow with blood,” “Gabar must be drilled from its peak to its base by oil drillers to be filled with explosives and blown up,” and “You can only appreciate the fact that our country is the most beautiful in the world after you see those mountains.” Sometimes statements such as these all appear in the same narrative.

At times, my interlocutors remembered the mountains as animated enemy spaces. They recounted favorably how soldiers changed the name of the Hayırlı (loyal and auspicious) Mountains across the Iraq border to their antonym Hayırsız (disloyal and worthless) Mountains because they harbored and hid “terrorists.” They described in pictorial detail each individual mountain so as to spatially anchor their stories about how they “couldn’t find the terrorists hiding in an underground cave just below their feet” or how “an army of terrorists could fit into just one of the hundreds of tunnels beneath the mountain.” Mountains are enemies not only because they harbor enemies and help them hide, but also because they wear out soldiers through their “ill-tempered” nature. In disabled veterans’ narratives, surviving on these rugged mountains is itself an act of heroism. Their accounts depict a desiccated landscape so steep that even mules and ibexes cannot climb the slopes. My interlocutors frequently emphasized the absence of inhabitants and plant growth on the mountain peaks as evidence of their incompatibility with life.

Reminiscing about mountains as enemy spaces conjured up conquest (gaza) imagery for my interlocutors. In spirited performances, they narrated the “adrenaline” of the ritualized combat practices of charging mountain peaks chanting “Allah, Allah”—the war chant associated with the Ottoman Janissaries—and raising flags after peaks have been captured. These customary practices closely echo the ritual structure of the Islamist-nationalist annual commemorations of the conquest of Constantinople. By building an analogy between the Janissaries climbing the city walls of Constantinople and present-day soldiers seizing the Region’s peaks, these exercises represent the “struggle against the PKK” as a holy war—in other words, a war against infidels. Through such practices, the Region’s mountains are marked as lands to be conquered and converted in order to remake the eternal home for the Turkish nation. The reconquest of the mountains is further accomplished through the mechanical reproduction of the soldiers’ conquering gaze, as depicted in souvenir photos in which my interlocutors pose on the peaks or point their weapons at the mountains on the horizon.

Soldiers on a “captured” hill. Credit: Depo Photos.

But disabled veterans’ narratives of their military service days are also tinged with lamentation and longing for a lost pastoral landscape: a pastoral devastated by war and littered with ruins and military garbage; a “traumatic pastoral”21 in which both nature and humans are perpetrators, victims, and witnesses of violence. Their narratives portray the sublime views from mountain peaks or the idyllic scenes of evacuated and then mined or booby-trapped mountain villages where spring water wells up in the inner courtyards of houses. My interlocutors affectively conveyed the ghostliness of these scenes by pointing out where on their bodies they had got the chills, usually on the napes of their necks or the back of their shoulders, when they first saw them. With pangs of guilt, they related how they had burned the beautiful orchards of empty villages so that they would not bear fruit for the consumption of “terrorists,” or how they shot down the “beautiful-eyed” mules of the guerrillas. They described despondently how the mountains have been turned into dumping grounds, rendering mine detectors useless in a land covered with bullet and shell casings and discarded tins of canned food.

The mountains are affectively charged locations in these disa...