![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Carol Vernallis, Holly Rogers and Lisa Perrott

Carol Vernallis: Intensified movements

Again, everything seems to have changed, and Transmedia Directors seeks to somehow capture this. Over twenty years ago, scholars like David Bordwell, Jeff Smith and Carol Vernallis began noting that directors and practitioners were producing work across multiple media – for instance, feature films, commercials, music videos and fashion photography (Smith and Vernallis have chapters in this collection).1 It wasn’t unusual for some of this work to be commissioned by production houses like Anonymous Content, Partizan and Good Company. Many of today’s biggest directors, like David Fincher and Francis Lawrence, developed their styles out of these contexts. We can see their stylistic traits – hyper-control, line and glide as well as a sensitivity to audiovisual relations – as derived from these experiences.

The roles of transmedial directors and practitioners have only intensified, as have those of production houses, which serve as hubs for all kinds of media-making, including feature films, long-duration, streaming web series, mini-docs, commercials, music videos and fashion photography, Instagram and Facebook posts, and their accompanying commercial spots (now shot in batches with a range of durations, say, from fifteen seconds to seven minutes, to be distributed across multiple platforms), VR and augmented reality. Much of this is now filmed in Los Angeles (not only because talent is deep but because everyone can drive within a day’s notice to almost any location – the beach, the mountains, the desert and to those that are wealthy or impoverished), but a good amount is also shot in suburbs and cities like Cape Town, Vancouver and Rio de Janeiro, because they can look American or European. For these locations, a handful of first-line talent (the director, the cinematographer and some of the performers) can be flown in, and the rest of the talent and labour can be local. Much of the work we see today isn’t of anywhere specific, and only certain types of directors succeed (those who work quickly, have interpersonal skills and can survive jet lag). Jonas Åkerlund has bragged that he enjoys circulating globally and collecting experiences, as he drops into and out of micro-communities.2

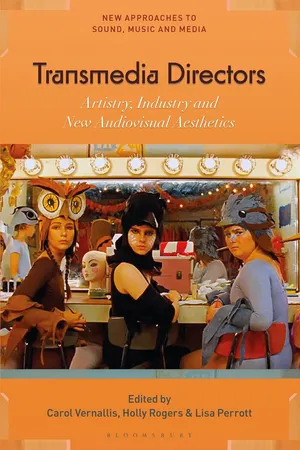

Catching this intensified media swirl seems daunting. It involves so many strands of production, from Instagram impresario Jay Versace’s thirty-second cell phone content (consumed by an audience of millions), to Michael Bay’s global billion-dollar financing of his Transformers franchise, but it is essential. In this volume, we look at directors, drawn to the way that many seem intoxicated by the possibilities of this media swirl. Wes Anderson, Lars von Trier, Michael Bay and David Lynch (who are discussed in the chapters) have designed theme parks, restaurants, museum exhibitions, speakers, furniture, wallpaper and diamonds, as well as fashion, opera stagings, commercials, virtual reality and streaming television. We think, perhaps, that the desire to reach past every moving media format into material objects is a drive to try everything possible, or a desire to touch, finally, a material shore.

In putting together this collected volume, we had quite a few questions: What is it about these directors and practitioners? Do they have better lives than us? Can we somehow emulate them? Do they know how to negotiate neoliberalism, precarity, austerity and work speed-up in ways we can adapt and use? Were they just producing content, or did they think deeply about platforms, genres and form? Were music videos their favourite medium (because experimentation, voice and imagination could resound in these), or was it the narrative streaming series that beckoned them, because characters could be subtly and contradictorily constructed? And how did they voice their work through practitioners? Did they hold them close and adapt to them? What happened when talent changed? Because many of our directors work across the same media, might they contribute to a new style? Could we assume that films and television (with their potential for world-building and sense of the past and the future), music videos (with their audio and visual aesthetics and rhythm), commercials (with their ability to project a message quickly), the internet (with its refreshed concepts of audience and participation) and larger forms like restaurants and amusement parks (with their materiality alongside today’s digital aesthetics) added up to something new? Senior directors, through their experience and influence, might project this new style, and students and younger artists would emulate it. The production houses seemed to share commonalities (i.e. what one director anonymously described as ‘a wan Terrence Malick filter’?).3 How much did they shape style? Instagram would need to be a piece. Would we wish to reassess concepts of authorship, assemblage, transmedia, audio and visual aesthetics and world-building?

There were other attractive tacks for our collection – some sort of Latourian actor network, where we would also track agents, signals and objects or an in-depth look at one or two directors from a wider range of perspectives. The term ‘transmedia’ (directors) in our title called for a synonym (like ‘cross’, ‘traverse’ or ‘through’), because transmedia is more often defined as a franchise aimed at monetizing a concept (Henry Jenkins and others are responsible for this scholarship; we find their notions of world-building particularly helpful, but we’re focused on the portability of the director and her style).4 Our instincts, we’ve realized, were good. We’ve captured much of what we were seeking, including confirmation concerning intensified audiovisual aesthetics centrality today. All our directors and practitioners are auteurs mélomanes (in Claudia Gorbman’s words), ‘music-loving directors [who] treat music … as a key thematic element and a marker of authorial style.’5 They seek novel realizations of the soundtrack in relation to the image. We assert that we need a new discipline, perhaps one called audiovisual studies.

Our approach – which features individual chapters and several modules on a number of today’s directors and practitioners – helped us feel closer to our moment, and more aware of unfolding trends. Insights emerged as chapters came in. Our ‘big’ directors projected something odd in relation to scale, and we suspect their use of scale links intimately with their success: skills in modulating scale may be crucial if one wishes to span the media swirl (from the Instagram pic to the streaming web series and big-budget film). As his module shows, Wes Anderson embraces the hyper-groomed, curated and miniaturized style (though he can quickly break out of this, like The Royal Tenenbaums’s family friend Cash’s lurid murals and extravagant car crash). Michael Bay’s images on the other hand (as our author Mark Kerins n otes, and he intends this as a compliment) could be seen as advertisements for Michael Bay. As Kerins observes, Bay’s stripped-down characters and plots flatten the director’s work, but they also make his products flexible and transportable. Lynch (and we’re aware that this sounds impressionistic) seems to release his projects synchronized to his format; his pitched audiovisual emanations, porous and oscillating in time, are tuned so that his commercial’s rhythms differ from a long-running TV show like Twin Peaks; both, however, feel as if they’d pre-existed as other points in the galaxy and were tied to one another – they are slices of Lynch. Barry Jenkins and his collaborators can suggest a heart-piercing humanism in one sustained shot (having African American actors directly addressing an audience is new for many), and his use of rhyme, poetic form and memory are equally important. Lars von Trier seems caught in some light/dark opposition, with works asserting greater grandeur than the forms can contain. His favourite techniques, including diagrams, plays with digital surfaces and tightly curated swatches of pop and classical music, facilitate these effects. Bowie, one of the most shape-shifting auteurs here, resembles a magpie, embracing a loose continuity; these contribute to his ability to cast a shadow even after death. Sofia Coppola’s scalar visions may be the hardest to describe. Much of her work suggests an oscillation between presence and absence, with the ‘now’ momentarily peeking into view. An inaccessibility and timelessness beguiles through her languid figures, handsome costumes, subtle lighting and pastel colours. We’d wish to provide similar descriptions for more of our volume’s subjects, such as Steve Wilson, Jess Cope, Jay Versace and Sigur Rós. These are our descriptions; you can catch your own from reading the modules. We’re excited about our short chapters, which place perspectives right up against one another. Overlaps and different facets quickly emerge.

Surface features appear to connect closely to scale (director Emil Nava’s and producer Calvin Harris’s structures against surfaces come quickly to the fore in their module). Our directors are good at what Richard Dyer calls the intangibles of media practice: colour, light, gesture, movement and music sound.6 Readers might keep an eye out for Wes Anderson’s bright yellow, Coppola’s soft pastels, Bay’s ‘blorange’ (saturated hues, with darks skewing blue and skin skewing orange) and Lars von Trier’s deep red and dull beige.

Our collection seeks to illuminate how directors work with both sound and image, and across various media. It also aims to show the ways they work in different contexts and their practices adapt over time. Uhlin’s and Connor’s chapters focus on auteurs and practitioners within the industry, and the ways technologies’ affordances facilitate their projects. Uhlin captures David Fincher’s deep ambivalence, his role’s (or function’s) requirement to project himself as an auteur as well as his desire to vanish, as a practitioner, from view. His recent work becomes possible not only through current, specialized forms of digital workflow (which Fincher helped design) but also through the collaboration of many specialists and their production houses. As Connor describes, Bong Joon Ho on the other hand seems transmedial not so much in the ways he works with content, as in how he crosses nations, corporations and other political, economic and social configurations. And he does this, as it seems many of our directors do, through a gesture, a concept or an image – Snowpiercer’s train (as a metaphor for narrative drive and capitalism), his hands making the shape of that train, and the beyond-negotiation-demand for a gimbal.

We did not write this collection to extol the great director. Instead, it’s because, as Warren Buckland suggests in his chapter, we as humans desire to engage with art forms as a means to both recognize ourselves and see past ourselves. I’ve had a chance to talk with and meet several of the leading directors and practitioners of today, and they seem just a bit more interesting and noticeably more anxious and driven than most of us. As co-editors, we see ourselves, with varying degrees of agreement and difference, as possessing progressive politics. In more generous societies, we’d hope everyone would have the abilities and resources to produce work if they so desired, and to be seen.

Some of our commitment to this collection comes out of overlapping political work; for me, much of this is tied to audiovisual literacy, and some of it to neuroscience and new technologies. I’m co-opting Sandberg’s line of ‘lean in’ (which Joe Tompkins has written beautifully on in relation to The Hunger Games series).7 I see merit in unplugging. But there’s also merit in engaging forcefully. We had long made a commitment to range and diversity, but in the interim, as we worked on our collection, #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite unfolded. My interviews with above- and below-the-line practitioners seemed to capture the industry’s new commitments to diversity and range. There’s clearly an increasing engagement with showing women and people of colour before the camera (most strikingly so with advertising to millennials). And perhaps as a related corollary, there’s new pressure to represent behind the camera too. I’m most moved by teams chosen by well-established production houses like Partizan (Michel Gondry’s company) and Anonymous Content and Reset (David Fincher’s former and current company).

This is a big volume. We’ve attempted to reflect gender, race, age, nationality, LGBTQ+ and disability. Some of the politics of our ‘highest profile’ directors are more conservative than ours (Lynch, Bay and von Trier have all expressed sentiments we can’t endorse), but more are committed to social justice. We feel our collection intersects with recent thinking about the interwoven nature of individuals, community and politics, and can be turned towards progressive ends.8

Our directors came out of fortuitous circumstances and biological predispositions (what might be called gifts and inheritances). Wes Anderson’s mother was an archaeologist and his father headed an advertising firm. Barry Jenkins and his colleagues attended Florida State University, where there was a remarkable level of energy, support and magic. Sofia Coppola’s father was Francis Ford Coppola, and she has imbibed cinema since infancy. Some of it’s serendipity (Bay got into trouble for blowing up his toy truck, an experience so overwhelmingly powerful he never let go of it), and some of it is biology. Von Trier and David Bowie have been forthright about being neuro-atypical, especially von Trier. But all of this is human and natural and understandable.

These artists’ trajectories have been shaped by context and serendipity: it’s partly a mystery (and probably some luck) how they developed, changed and persevered. Jenkins waited eight years between his Medicine for Melancholy (2008) and Moonlight (2016) films, and suddenly he’s in the midst of If Beale Street Could Talk (2018) and the forthcoming TV series The Underground Railroad. It would have been hard to imagine, watching 1980s and 1990s music video directors at the time, that Dave Meyers’s videos would contribute so much to the genre’s potential as an art form in such surprising ways.9

We attempt to capture how directors’ work has evolved as they’ve worked across media, though this can be elusive. The most in-depth descriptions are in the chapters on Michael Bay, Dave Meyers and Sophia Coppola: music videos still cast an influence on their work. Some influences can be gauged by imagining past this volume. One might speculate on the ways Wes Anderson’s work will shift after his recent experiences curating a major museum exhibit (he handled thousands of art objects and whittled these down to a few – surely, given his past predilections, this would make a difference). He’s just come out with wallpaper. And one wonders about the origin and development of David Fincher’s meticulousness (which some claim is obsessive). Can we give music video some credit for this? Fincher has described music video as a director’s sandbox, and because there isn’t much dialogue, he must have spent a lot of time watching bodies within shots passing against the music, over and over again. Who wouldn’t, with Fincher’s inclinations, hunger for a perfect line? Traces of his early music video work appear in his recent films, like Amy Dunne’s celebratory leap into the air in Gone Girl (2014), having successfully escaped the police. Her euphoric movement matches some of the leaps in Paula Abdul’s ‘Straight Up’ (1988), Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ (1990) and Justin Timberlake and Jay-Z’s ‘Suit & Tie’ (2013). Her lacing her ballet shoes on the way to eviscerate her ex-boyfriend may draw inspiration from Abdul’s ‘Coldhearted Snake’ (1988).

The ways directors in this collection depend on their composers and other practitioners highlight a central political point, which is that we’re bound to one another: no artist makes it alone, and the same is true for ourselves. As Theo Cateforis and Ewan Clark note, it’s not completely clear if Anderson had a beloved, relatively whole sound world prior to his collaborations with composer Mark Mothersbaugh, or if they co-created one together. When his next composer, Alexandre Desplat, began contributing, we don’t know if he chose materials out of a respect for Mothersbaugh, to follow Anderson’s taste, to maintain a house brand, or that these musical materials just seemed apt for these films’ images. Still, one gets a sense how much Anderson, Mothersbaugh and Desplat became indebted to another. Perhaps similarly, Jenkins has found practitioners who beautifully augment his work, as cinematographers and sound designers, as has Nava with music producers and colour timers. Jess Cope and Steve Wilson seem intimately close. Floria Sigismondi has described her connection to Bowie as beyond the human. Schott’s and Barbour’s chapter on Sigur Rós shows the ways a song can carry such a clear message that no additional instructions need be included: we all want to be on the same wavelength, especially when thinking about our planet’s future.

What is it about these directors and their work, and how do they get us to better lives and a better world? Dyer says that music as a part of audiovisually enlivened, popular media creates feelings of utopia, but offers no roadmap to get there. Jenkins and Meyers may provide possible paths.10

But these directors produce messages that are new and in sync with our time. They first capture us, as Dyer and Carl Plantinga argue, with an unpackable conundrum.11 Buckland sketches this most fully with his description of Anderson’s ironic sincerity. It’s also in Lynch’s and von Trier’s euphoric generosity, violence and terror. And, perhaps, in Michael Bay’s benevolent, extravagant figures – mechanical objects whose source remains unfathomable. And Jay Versace’s desire to be king, even though he’s on Instagram. These transmedia artists all stretch out to the world. (One can feel invigorated when those mechanical transformers twist their way up to an er...