1

FOOTSTEPS THROUGH THE CITY

Social Justice in Its Multiplicity

Day after day I gaze in gratitude

on the Castle of Prague

and on its Cathedral:

I cannot tear my eyes away

from that picture.

It is mine

and I also believe it is miraculous.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

What bliss it is

to walk upon this bridge!

Even though the picture is often glazed

by my own tears.

Jaroslav Seifert, “View from Charles Bridge”

September 28 is a public holiday in the Czech Republic, honoring the life and death of the tenth-century political and religious leader Saint Václav (svatý Václav), or, as he is known in the English Christmas carol, “Good King Wenceslas.” Public processions, Christian Masses, and historical reenactments of events from the great saint’s lifetime are held in cities and towns across the nation. Pilgrims from around the country descend on the town of Stará Boleslav, where Saint Václav met his demise in either the year 929 or 935 (the exact date of his death remains in dispute). Simultaneously, the nation celebrates “Czech State-hood Day,” since as of 2000, September 28 doubles as the national commemoration of the founding of the Czech state.

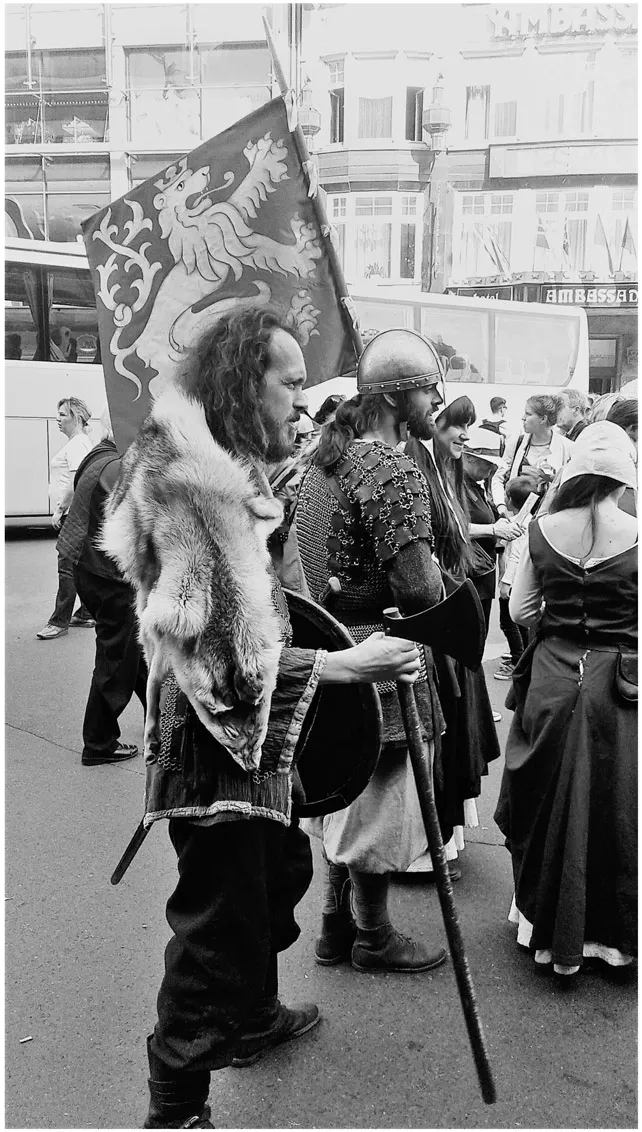

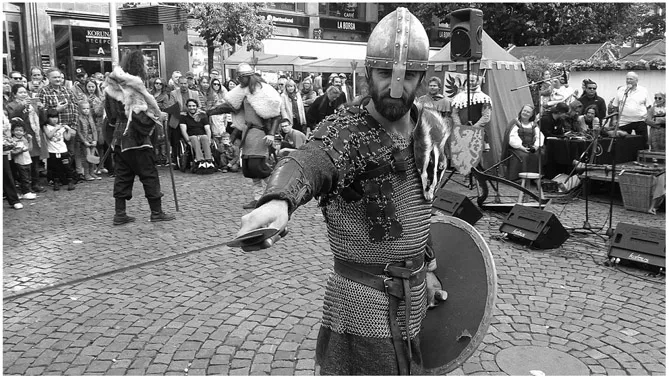

In Prague, locals and visitors alike can make the most of the holiday by traveling from one celebration to another. In 2016, in the center of town on Wenceslas Square (Václavske náměstí), a popular tourist spot named after the saint but also a notorious drug and prostitute hangout in the evenings, there was a reenactment of Saint Václav promenading into town on horseback followed by his medieval knights. Men dressed in furs and carrying swords and shields paraded around the square before undertaking mock battles at the saint’s request.

From what we know, Saint Václav’s reign was in fact a tumultuous one. In the West, he is primarily recognized for his care of the poor, giving alms to the destitute on the feast of Saint Stephen on December 26 as the Christmas carol attests. In the Czech Lands, he is similarly hailed as a brave and just ruler who focused on protecting the nation’s interests rather than amassing his own fortune. But after only about a decade of rule, Saint Václav was murdered, many presume by his younger brother Boleslav, who then took over the monarchy. The 2016 reenactment, however, referred to an easier time, and after a short battle, the men laid down their arms. Saint Václav then exchanged his horse for a throne, and a bevy of women dressed in medieval costumes accompanied by folk musicians began to dance.

In Stará Boleslav, the celebrations were more somber. Around a thousand pilgrims, many of whom had walked about thirty kilometers on foot from Prague, assembled for Mass outside the local church where Saint Václav was murdered (“Průvod s ostatky” 2016). Held aloft in a portable reliquary, Saint Václav’s ornately bejeweled and crowned skull, which had also made the ceremonial journey from its home in a Prague crypt, joined the procession before being put on display.

In 2016, the Czech president, Miloš Zeman, who had originally been an out-spoken critic of the move to couple Czech Statehood Day with the celebration of a major religious figure, made his first-ever appearance at the Mass. Before the assembled brethren and with cameras and microphones transmitting live to the nation, President Zeman took to the podium and cited the Biblical verses “God is love” (Saint John) and “[If I did not have] love, I would be nothing” (Saint Paul), following which he declared, “Remember these words in a time when all of Europe is looking again for its cultural roots in the fight against Islamic fundamentalism. We must do all we can to make sure we truly return to these roots” (“Den české státnosti” 2017; author’s translation).

Many of the people commemorating Saint Václav’s Day wouldn’t have worried about what Zeman’s comments were that day. They were out to have a good time, eating and drinking while enjoying the late autumn sunshine. But for others, joining the religious procession or taking part in commemorative Masses was a welcome opportunity to engage with the country’s religious and political heritage. But what direction did the president suggest they should head in? Was he advocating for more tolerance and love toward others, or for closing the doors to those deemed to be threatening the “cultural roots” of Europe?

FIGURE 1.1. Preparing to reenact Saint Václav’s procession on Saint Václav’s Day, an acting troupe assembles on Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Photograph by John M. Correll.

FIGURE 1.2. An actor portrays Saint Václav in battle. Photograph by John M. Correll.

Given Zeman’s well-known antipathy toward refugees, his summoning of the nation’s Christian heritage was clearly part of an ongoing effort to bolster public antipathy toward Muslims. But as the possible double meaning of Zeman’s use of biblical verses demonstrates, his invocation of the nation’s history could lend itself to various moral framings. Indeed, walking through the city, whether as part of a pilgrim’s procession, engaging in historical reenactments of Saint Václav’s promenade, or simply traversing from one place to another, highlights the multiplicity of ways that morality and social justice can be constituted with respect to both historical events and the contemporary. What we must do, to echo Zeman, and how we must do it are in fact radically contested issues that draw on a range of historical narratives we meet up with as we move through urban spaces.

What is at stake in choosing between these narratives is not only the question of what role Christianity should play in the contemporary state, but also what makes a good and just political leader—should one expect today’s politicians to follow the model of Saint Václav, for example? What are the state’s responsibilities to the nation’s citizenry? How do individual citizens, including those striving to live just and moral lives—aiming to “live in truth,” as Patočka, and later Václav Havel, phrased it—envision a just society, enabling the development of the individual while also promoting the “greater good”? Who gets to take part in such a society and who is left or actively cast away on its outskirts? And what role might entities other than the state, such as corporations, play in constructing, or supporting, social justice?

One way of trying to get a grip on such questions is to walk our way through them. The accounts that follow were generated by walking with local residents through three well-known Czech cities—the nation’s capital of Prague, the industrial center of Ostrava, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization heritage site of Český Krumlov—and along the way, encountering various aspects of how history and social justice are evoked by urban landscapes. In retracing these steps here, our meanderings will reflect how Czechs both create a sense of collective belonging and exercise powers of exclusion in order to enact their visions of a just society.

Prague: The City as a Space for Life

Walking through Prague, one is struck by all the green spaces: the grounds around the castle, the Royal Garden, the lawns of the Petřín observatory tower. On a spring or summer’s day, the sidewalks, parks, and playgrounds teem with people. Stromovka is full of families, some returning from a jaunt to the zoo. A younger crowd congregates in Letná, sunning themselves, drinking, playing guitar: one group smokes a hookah, another does tai chi in the park. Public space—once a site characterized by intense scrutiny and concern over what could and could not be revealed in a totalitarian state—has been transformed into a site for the celebration of life. Not everyone is jovial, however, as young men who have had too much to drink vomit next to buildings. Couples are caught in arguments, trying to sort out or dissolve marriages.

The city is also a site of anxiety, particularly among those who cannot make it, or feel they cannot make it, in the new space of capitalist entrepreneurship. In the city center, there are fancy sleek black cars (Audi, BMW) and men sporting well-cut suits. Taxi drivers shake their heads in awe, noting how fantastically the economy is doing. But those who are not sharing in the wealth are also appearing in greater numbers. Homeless people are increasingly visible; not only men or young people but middle-aged women, some with children, sit next to upturned hats that contain a stray coin or two, begging for money.

In recent years, economic disparities have increased tremendously. While unemployment in the capital is extremely low—at 2.5 percent in 2017, Prague has the lowest unemployment rate of any city in the European Union (EU)—the number of people living precariously is growing, due to the high cost of living coupled with some of the lowest wages in the EU (“České mzdy” 2017). In a country that once ostensibly had no homeless people, there are now approximately 4,000 people (out of a total population of about 1.3 million) living rough in the capital (Scott 2013).

There was a time when combating poverty was part of the purview of the nation’s monarch. Certainly Saint Václav’s efforts in this respect are central to his image as a just and noble ruler. In a postsocialist landscape dominated by corporate capitalism and cronyism, today Saint Václav’s largesse is held out as exemplary, but amid ever-troubling questions of how best to strive toward social justice and ensure the dignity of “ordinary people” within a twenty-first-century democracy.

Walking through Time

At the top of Prague’s Wenceslaus Square stands a massive statue of the saint on horseback. A striking symbol of Czech nationhood, the statue is a popular meeting spot and assembly point. During the 1989 uprisings against state socialism, protesters did not need to disclose where to meet up, as people intuitively knew the demonstrations would start at Saint Václav’s feet (Holy 1996, 34). Legend has it that should the Czech Lands ever be under threat, the statue of the Good King and his steed will spring to life, hurtling down the boulevard and assembling his many hidden knights, before leading Czechs to victory.

Consciously invoking these kinds of legends is one way of explicitly conjuring up historical narratives and placing oneself among them. Other gestures to the past are less mystical. They can be fleeting, as when, walking up Prague’s Petřín Hill on a family excursion, my friends wave toward the Hunger Wall, reminding everyone in our group how during a fourteenth-century famine King Charles IV ordered its construction in order to provide paid employment for the poor and thus alleviate their hunger. This is just one of many passing moments of historical reemergence, made possible by moving from one place to another for an entirely different purpose, but nonetheless taking the time to underscore the historicity inherent in the objects and places we live among.

Other gestures are more self-consciously elaborate, as when my friends Jarda and Veronika, who are both in their early sixties, took me on an extraordinary, five-hour historical walking tour of Prague. Each step was punctuated with multiple, crisscrossing historical legends. At Vyšehrad we stood on the fortress ramparts overlooking the river, as Jarda and Veronika eagerly narrated the story of Libuše, the prophet and female founder of the ruling Přemyslid Dynasty, who in the eighth century had a vision of where to build the city of Prague. “Look at the curve of the river and how the landscape opens up before you,” Jarda, who is an engineer, prompted, “and you can see why this particular spot would be strategically the most advantageous place to build a fortification.” Crossing Charles Bridge provoked accounts of the exploits of King Charles IV, who initiated its construction, just as Prague Castle’s Saint Vitus Cathedral spurred stories about Saint Václav, who oversaw the building of the first church there. And so it went, the account of one legendary leader following after another. Not only did each of these leaders help make the city into what it is today, but, as their stories attest, they were thought to be endowed with extraordinary physical, mystical, or intellectual abilities as well as a deep sense of justice and a willingness to work for the collective good. While geographically the stories flowed easily one into another, temporally we took giant leaps, jumping ahead four or five hundred years, only to fall back in time again.

FIGURE 1.3. Prague skyline with statues of saints on Charles Bridge. Photograph by the author.

Along the way, we took frequent breaks to take in the views. Not everyone can express it as eloquently as the poet Jaroslav Seifert in the epigraph to this chapter, but admiring a stunning vista (of which there are thousands) and feeling moved by it are commonplace activities. While we often associate such activities with tourists (Selby 2004), it is not uncommon for long-term residents of Prague to frequently take a short stroll through the city just to stop and appreciate its beautiful views. Over the years many have tried to convey to me the power of Prague’s beauty and what it means to them; one relative simply handed me a book of Seifert’s poems and suggested I read it to understand. Jarda and Veronika are no different in this respect, deeply moved by the aesthetics of the city that they have lived in for six decades.

But while I was fascinated by how our journey made the historical landscape come alive around us, this feeling was not at all new to them. In fact, our footsteps retraced a walk that Jarda and Veronika used to take every year with their children as they were growing up. Back then, each child was given the task of learning a new story or legend to share when they reached a particular spot, be it one of the thirty-one statues of saints and historical personages that line Charles Bridge (or, in the case of Prince Bruncvík’s statue, stand on the bridge’s pier) or the cannonball that remains embedded in Vyšehrad’s eleventh-century rotunda. The walk became not just a history lesson but a process of linking stories and legends to the material realities in their midst, enabling an old building, statue, or monument to rise to new significance while remaining a vivid part of the contemporary landscape.

FIGURE 1.4. Visitors and locals making their way across Charles Bridge. Photograph by the author.

How we come to commemorate events and link them to a specific place is as much about how we view the present as it is about any given place’s actual past. History always inheres in places, whether we actively recognize it or not. History resides in the buildings, the turns of the street, the cobblestones we slip on in the rain. Prague’s Old Town, whose inhabitation is thought to date back at least to the ninth century, reflects close to a millennium of urban development. Despite being the site of armed takeover by the Nazis during World War II and a Soviet tank deployment in 1968, much of the city remains largely undamaged and retains its historical character. Today Malá Strana (the Lesser Town) is the setting for internationally produced movies that need an eighteenth-century backdrop. But it is also the space of contemporary life, of buses and commuters, bars and ice cream shops, parks and playgrounds.

FIGURE 1.5. Cobblestone road and sidewalk leading up to Prague Castle. Photograph by the author.

Indeed, in historic cities like Prague, negotiations of old and new constantly take place. When the building of a McDonald’s a few minutes’ walk from one of the entrances to Charles Bridge was proposed after the 1989 revolution, it was denounced for disrupting the historical character of Malá Strana. (Now it only elicits bad reviews on TripAdvisor.) Today, Prague’s “new” Dancing House (Tančící dům), built in 1996 and designed to visually evoke Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dancing, graces the riverfront to the delight of tourists and the continuing horror of some residents who told me they are confounded by “the mix of old and new.” Why is this building so upsetting when not far away from Fred and Ginger stand a series of Cubist buildings, built at the start of the twentieth century, that seem even more architecturally distinctive? But the Cubist buildings are now part of history, while, for many, Fred and Ginger are not (yet).

What then is considered history? Beyond rituals of commemoration, how do we actively invoke history in some places, coming to embody historical narratives through, for example, our daily traversing through time and space? Here we can get some help from both Heidegger’s and Patočka’s understandings of thrownness, movement, and perception.

One way that Heidegger described the work of history was through the concept of thrownness, or how as human beings we are thrown into a particular time and place where we must enact our lives. Thrownness, according to Heidegger, is at the heart of the human struggle, as it results in inevitable feelings of guilt. We are never at the very beginning of an event, but are instead thrust into a time and place that are already constituted. As such, we come into a situation already ripe with choices, paths, options—and not only those w...