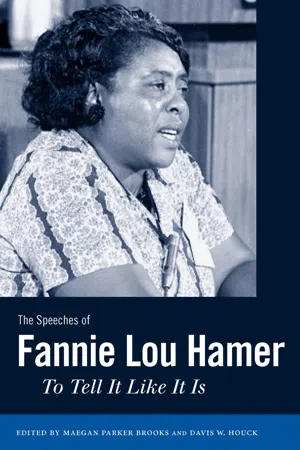

The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer

To Tell It Like It Is

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer

To Tell It Like It Is

About This Book

Most people who have heard of Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977) are aware of the impassioned testimony that this Mississippi sharecropper and civil rights activist delivered at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Far fewer people are familiar with the speeches Hamer delivered at the 1968 and 1972 conventions, to say nothing of addresses she gave closer to home, or with Malcolm X in Harlem, or even at the founding of the National Women's Political Caucus. Until now, dozens of Hamer's speeches have been buried in archival collections and in the basements of movement veterans. After years of combing library archives, government documents, and private collections across the country, Maegan Parker Brooks and Davis W. Houck have selected twenty-one of Hamer's most important speeches and testimonies. As the first volume to exclusively showcase Hamer's talents as an orator, this book includes speeches from the better part of her fifteen-year activist career delivered in response to occasions as distinct as a Vietnam War Moratorium Rally in Berkeley, California, and a summons to testify in a Mississippi courtroom. Brooks and Houck have coupled these heretofore unpublished speeches and testimonies with brief critical descriptions that place Hamer's words in context. The editors also include the last full-length oral history interview Hamer granted, a recent oral history interview Brooks conducted with Hamer's daughter, as well as a bibliography of additional primary and secondary sources. The Speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer demonstrates that there is still much to learn about and from this valiant black freedom movement activist.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Federal Trial Testimony, Oxford, Mississippi, December 2, 1963

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- “I Don’t Mind My Light Shining,”

- Federal Trial Testimony, Oxford, Mississippi, December 2, 1963

- Testimony Before a Select Panel on Mississippi and Civil Rights, Washington, D.C., June 8, 1964

- Testimony Before the Credentials Committee at the Democratic National Convention, Atlantic City, New Jersey, August 22, 1964

- “We’re On Our Way,” Speech Delivered at a Mass Meeting in Indianola,Mississippi, September 1964

- “I’m Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired,” Speech Delivered withMalcolm X at the Williams Institutional CME Church, Harlem, New York,December 20, 1964

- Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Elections of the Committee onHouse Administration, House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.,September 13, 1965

- “The Only Thing We Can Do Is to Work Together,” Speech Deliveredat a Chapter Meeting of the National Council of Negro Women inMississippi, 1967

- “What Have We to Hail?,” Speech Delivered in Kentucky, Summer 1968

- Speech on Behalf of the Alabama Delegation at the 1968 DemocraticNational Convention, Chicago, Illinois, August 27, 1968

- “To Tell It Like It Is,” Speech Delivered at the Holmes County, Mississippi,Freedom Democratic Party Municipal Elections Rally in Lexington,Mississippi, May 8, 1969

- Testimony Before the Democratic Reform Committee, Jackson, Mississippi,May 22, 1969

- “To Make Democracy a Reality,” Speech Delivered at the Vietnam WarMoratorium Rally, Berkeley, California, October 15, 1969

- “America Is a Sick Place, and Man Is on the Critical List,” Speech Deliveredat Loop College, Chicago, Illinois, May 27, 1970

- “Until I Am Free, You Are Not Free Either,” Speech Delivered at theUniversity of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, January 1971

- “Is It Too Late?,” Speech Delivered at Tougaloo College, Tougaloo,Mississippi, Summer 1971

- “Nobody’s Free Until Everybody’s Free,” Speech Delivered at the Founding ofthe National Women’s Political Caucus, Washington, D.C., July 10, 1971

- “If the Name of the Game Is Survive, Survive,” Speech Delivered in Ruleville,Mississippi, September 27, 1971

- Seconding Speech for the Nomination of Frances Farenthold, Delivered atthe 1972 Democratic National Convention, Miami Beach, Florida,July 13, 1972

- Interview with Fannie Lou Hamer by Dr. Neil McMillen, April 14, 1972, andJanuary 25, 1973, Ruleville, Mississippi; Oral History Program, University ofSouthern Mississippi

- “We Haven’t Arrived Yet,” Presentation and Responses to Questions at theUniversity of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin, January 29, 1976

- Appendix

- Acknowledgments

- Suggestions for Further Reading and Research

- Index