eBook - ePub

The Candle and the Guillotine

Revolution and Justice in Lyon, 1789–93

This is a test

- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As in a number of France's major cities, civil war erupted in Lyon in the summer of 1793, ultimately leading to a siege of the city and a wave of mass executions. Using Lyon as a lens for understanding the politics of revolutionary France, this book reveals the widespread enthusiasm for judicial change in Lyon at the time of the Revolution, as well as the conflicts that ensued between elected magistrates in the face of radical democratization. Julie Patricia Johnson's investigation of these developments during the bloodiest years of the Revolution offers powerful insights into the passions and the struggles of ordinary people during an extraordinary time.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Candle and the Guillotine by Julie Patricia Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & French History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

INSPIRATIONS

Chapter 1

THE MOST POLISHED TOWN

Lyon was distinguished before the revolution not only as a place of manufacture, but as a place of literature and science.

—Anne Plumtre, 1810

A writer by the name of Anne Plumtre took advantage of the Peace of Amiens in 1801 to travel from England to see for herself what changes the Revolution had made in France. She was especially interested in the provinces, and in addition to a period of residence in Paris, she made an extended stay in Lyon. Plumtre found the region to be very ‘different’ and more inspiring than the observations of travellers, who only visited Paris and did not stay anywhere long enough to become ‘habituated’ to the people.1 Plumtre got to know the Lyonnais and was most interested in their stories, especially as they related to the period leading to the Revolution. Lyon, she observed, was ‘reckoned before the Revolution, the most polished town in France, after Paris’ with its buildings, its academies, its theatre, its famous college and library, and these famous landmarks were still to be admired when she lived there. She estimated its population at some 120,000 (historians now suggest it was more like 150,000), many of whom were involved in the lucrative silk trade, which had become the predominant industry.2 The city, its trade and its population, she noted, had been uniquely affected by the Revolution. To appreciate how Lyon navigated the changes the Revolution brought, we do need to imagine what life there looked like at the time.

Silk had become the predominant trade in Lyon from its origins in 1562 and was known generically and simply as ‘La Fabrique’. Lyon had grown to become the largest provincial city in France because of this trade in silk, and a number of important consequences flowed. Because silk was a commodity needed for the court of the French kings and for other European courts, it meant the city gained a sort of notoriety and uniqueness. By the time of the Revolution, this notoriety was not one the citizens welcomed. The special status gained by the city for producing the luxurious fabric of silk for the royal court encouraged various careers in the silk industry, but there was less opportunity for other occupations. No university or parlement (independent court) was established here. There were also fewer noble families in the city but an influential mercantile elite who flourished because of the silk trade. These unique characteristics of the emphasis on a mono-industry were not considered a problem until a series of crises impacted the production of silk from 1782. Until then, the benefits of a creative and large workforce were widely admired. ‘Universal’ fairs were held here four times a year, when merchants from overseas and from within France congregated in the city to buy and sell wares.3 ‘Thousands of workshops’ operated to supply elaborately worked fabric, which was sold by the ‘hundreds of merchants’ of the city.4 Silk was by far the biggest export of the city, and at the time of the Revolution the trade extended to North Russia, Germany, the Levant and to a lesser extent to Spain and Italy.5

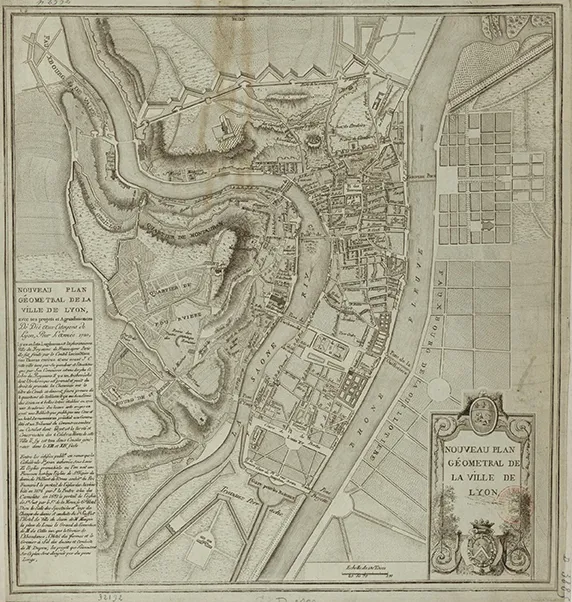

Figure 1.1 Plan géometral de Lyon, 1789 (Map of Lyon). Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon.

The richer silk merchants at first hung their blasons inscribed with their coat of arms in the most coveted addresses of the Rue Juiverie in the Saint-Paul area of the old city (Vieux Lyon).6 Financial transactions took place in a palatial building known as the Loge de Change, close to the Saône River, and there were many turreted houses owned by silk merchants that extended up the Fourviere hill in the narrow, winding medieval streets. Monasteries and churches in gothic and medieval style mingled with the remains of the ancient Roman city that had been established here on the right bank of the Saône River in 43 BCE. Gradually, as the silk industry attracted more workers, however, the commercial centre moved from the cobbled streets and the hotels and shops to the peninsula. An imposing Bourse (Stock Exchange), the Hôtel de Ville, the neo-classical buildings of the Place Terreaux and the mansions that surrounded the square of Bellecour with its equestrian statue of Louis XIV were constructed. The hospital called the Hôtel-Dieu situated on the right bank of the Rhône was extended by the architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot in the 1760s and became an important place for medical research. Businessmen could now hail a ‘batelière’, one of the numerous women who touted for business at the port and manoeuvred their small craft skilfully across the Saône using large metal poles (known as Harpics).7 There was a stone bridge where pedestrians could also cross from the Loge de Change to the newer centre on the peninsula, and on the other side was the newer wooden structure of the Pont Morand.

The two navigable rivers, the Saône and the Rhône, flowed around the peninsula. The fortresses that had dominated the surrounding hills were still there but had been allowed to fall into disrepair because, despite the proximity of the city to Piedmont-Sardinia, there had been a century and a half of peace along the southern border.8 Offices of the négociants (the grand merchants) in the city centre remained closer to the River Saône, which was less tumultuous than the Rhône, and thus had more useful ports. The silk weavers moved higher up the hill known as the Croix-Rousse to specially constructed houses with long windows that maximised the light but were sufficiently far away from the humid conditions near the rivers not to damage the silk. A series of covered passageways called traboules were used by journeymen to carry the cloth from their buildings higher up and through the stone flagged buildings that led down to the port. The specially constructed route, of deep stairs and long corridors, enabled the heavy bolts of silk to be carefully manoeuvred whilst being protected from the sun and rain. The valuable cargo was loaded onto the ships that would take them to the European clients.

Clients were sought by enterprising merchants, like Joseph Chalier, who travelled widely in Europe. He had been born to a bourgeois family of solicitors at Beaulard, in the mountainous region of Piedmont, and was sent to Lyon for his education. Here he took some lessons in design and architecture and was offered employment with Soufflot. However, he was more attracted by another offer of employment from one Muguet, who gave him a job as a silk négociant, which involved travelling in Europe and the Orient, visiting foreign clientele of the commercial enterprise. Chalier wrote of his success in his endeavours, recovering a creditable tally of debts for his employer over some fifteen years.9 As his experience indicates, work as a top-level négociant was lucrative. Merchants dealt with all aspects of the trade, including sourcing the thread and negotiating with the clients and the artists who made the patterns. They also sold the raw silk, the patterns and the orders to the weavers. When the work was completed, they then negotiated what was paid to the small manufacturers, ensuring that the market price of the worked silk stayed competitive.10 In effect, they retained profits when the manufacturers could sometimes barely make ends meet. This inequity was widespread, in spite of the fact that the manufacturing process demanded special skills and equipment that the silk manufacturer himself possessed. Even though Chalier himself was later to become active in revolutionary justice and politics, many others in the silk trade continued to aspire to the wealth and independence that becoming a négociant promised.

Jean-Jacques Ampère was another négociant who would also become a judicial officer after the Revolution. He had a strong family connection with the silk industry, as the second of four sons of François Ampère, a master silk worker. His brothers were also master silk workers, but Jean-Jacques himself had become a high-level trader by the age of 25.11 At the time of his marriage in 1771, one of his brothers (Jean-François) and Claude Joseph Desutières-Sarcey, his father-in-law, were also listed in the matrimonial record as négociants.12 His trajectory also suggests that until 1782, when he decided to leave the silk industry, upward mobility was still possible in the industry. There was, however, also an unusual cosmopolitan mix of talented artisans in the urban centre of Lyon, many of whom had become impoverished silk workers and who wanted to see real and lasting change in their work conditions as well as those who had become established as a mercantile elite and who wanted their privileges to remain virtually unchanged.

The manufacturers involved in the silk trade had typically learned the various aspects of the career over their lifetime. They worked in a type of cottage industry team that rarely exceeded five workers. Most of the work was actually done by members of their own family, including women and children from the age of 13 or 14. Women were paid less than men, often nothing at all if they were in a family business, but they were not able to progress in the hierarchy. Some girls were encouraged to work for five or six years to help secure a dowry.13 The long period of apprenticeship of men silk workers, of five years plus a further five years as a compagnon (traveller), and their ownership of the tools of the trade, meant they were ambitious and personally invested in the industry.14 Known as canuts, after the tool they used in the weaving process, the workers felt proud of their status and put in long hours to get ahead. They aspired to become a maître-ouvrier and then possibly a marchand and finally a négociant.

The reliance on the silk trade, so critical to the commercial success of the city, became by the time of the Revolution a liability to the larger workforce because of the limited focus of those involved in it. The ‘proto-industrial’ structures of the industry meant that by the late eighteenth century the majority of workers were tied to a lowly paid trade. There was a desperate need for increased investment to ensure continued growth.15 A temporary decline in demand for silk in 1778 coincided with increased costs of financing new methods of production, and this led to a crisis point in 1782, when stagnation and even bankruptcies were reported.16 Because consumers of the luxury fabric were usually only the aristocrats and the royalty, the financial difficulties experienced at Versailles before the Revolution also had a huge impact on Lyon. Marie-Antoinette’s decision to dress in more simple fabrics and the Eden Treaty of 1784 aggravated the poor economic situation.17 This treaty was the result of an agreement to reduce tariffs on imported cottons and linens, made cheaply in factories in England, which then made these fabrics more competitive against locally produced silk. Such a series of crises only increased the dependence of interests of those heavily invested in the industry.

Some négociants at the highest level avoided the crises of the eighteenth century because they were able to diversify and lessen their risk of losing money by investing in property. They actually continued to accrue wealth from the profits they made from rents and the returns on providing capital for business.18 However, others did not accumulate enough to p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I. Inspirations

- Part II. Aspirations

- Part III. Retributions

- Conclusion

- Glossary of Terms

- Glossary of Names

- Bibliography

- Index