Chapter 1

The Forces that Push and Pull

Viewed from our vantage point, the first half of the twentieth century appears as a vast panorama of catastrophe all along the “Dark Continent.”1 The storyline is a familiar one: war, revolution, and general strife accompanied by the disintegration of empires, the radical remapping of Europe, and the rise of new nation-states, followed a mere twenty years later by yet another round of calamitous, more murderous warfare. This was supposedly the great age of “the unmixing of peoples,” as Lord Curzon famously put it, but it could very well be understood as precisely the opposite.2 Violence and poverty forcibly propelled men and women from their homelands, stimulating waves of migration that pulsated across the continent throughout the last decades of the nineteenth century and into the first half of the twentieth. They left in search of peace and bread and many found both in France.

In addition to the promise of safe haven, European men and women were drawn to France by the everyday allure of employment and a decent wage. As industrialization accelerated in the late nineteenth century, French employers came to rely increasingly on free, unregulated border migration from Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and Spain to supplement the native labor force. And, by the early twentieth century, colonial labor migration from North Africa, especially Algeria, was also quite common. During the Great War, the large-scale mobilization of Frenchmen coupled with the demographic deficit that had long afflicted France created additional labor opportunities for colonial and European migrant workers. From Polish farming families at the turn of the century to seasonal female migrants from Italy on the eve of war, from colonial factory workers at the start of the Great War to the legions of demobilized soldiers that war left behind, French industry increasingly partnered with state officials to direct foreign labor into those sectors most affected by labor shortages.

Though scholars have long been attentive to the growing governmental impulse to control, regulate, and channel immigrant and colonial workingmen in France during and immediately following the First World War, they have been less attentive to how Catholic employers’ ideas about gender and sexuality shaped the organized introduction of foreign labor into specific sectors of the French economy, and the agricultural sector in particular where foreign families and immigrant workingwomen clustered.3 Meanwhile, although historians have successfully demonstrated how French employers inscribed gender inequality between the sexes, most notably in the textile industry and on the factory floor, they have yet to consider how a post–World War I atmosphere characterized by mass mobility and gender crisis influenced employer practices toward immigrant workingmen and workingwomen, specifically.4 In fact, interwar employers in agriculture and industry as well as their labor recruitment organizations experimented with marriage- and family-making policies in the hopes of persuading rootless, foreign-born wanderers to remain, at least long enough to bear the generations of French-born children the French themselves had lost. In this, the social Catholic conservatism that had long shaped the patronat’s worldviews became outfitted to a modern industrial age. In other words, interwar employer paternalism adjusted to the realities of an increasingly foreign-born workforce who, in their view, would require sexual management.

This chapter reconstructs the laboring lives and winding trajectories of immigrant men and women, agricultural laborers and factory workers who lived in and moved frequently between the countryside and urban centers throughout France, often against employers’ wishes and in rupture with their work contracts. It explores the gendered mobilities of foreign men and women in France during and after the Great War, the cultural anxieties their wanderings elicited from middle-class Frenchmen and -women, and how those moral fears shaped Catholic employers’ evolving policies toward them. Above all, it points to some of the ways that French employers and officials hoped to control and contain their movements in the 1920s, in order to encourage them to put down roots and dissolve at last into the great French nation of families. As European and colonial migrants drifted through Europe and alighted in France, barons of French industry and agriculture sought to make of them families, or remake them as such, if necessary.

The Forces that Push and Pull

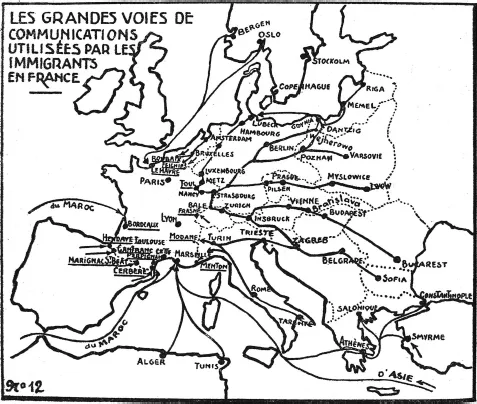

Though a handful of French employer syndicates had dabbled in organized labor migration before 1914, the war inaugurated a new age of state- and employer-directed foreign labor recruitment to meet the growing demands of the French economy. Although the native labor shortage resulting from the removal of most able-bodied Frenchmen to the front precipitated these measures, the closing of national borders accompanying the onset of war also stifled spontaneous border migration particularly from Italy, which had long served as a crucial labor reservoir for France. French employers thus took great pains to draw European and colonial workers to France and then direct them toward specific industries. In the face of the mass internationalization of the workforce in France, a newly minted category of “work scientists” took advantage of the opportunity to measure, hierarchize, and racialize immigrant labor, and their conclusions in part determined how foreign-born labor was allocated.5 Consequently, colonial and Chinese laborers were sent to docks and into military construction; Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian workers to agriculture; and Greeks, Armenians, and Italians toward industry, and more specifically, wartime munitions factories.6 To ensure the regular entry of foreign workers into France, foreign labor recruiters pieced together transportation networks crisscrossing the continent. As the map below renders visible, all immigrant roads—railroads, as well as steamships, in this case—led to France after the war (figure 1.1).

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, immigrant women had also heeded the invisible call of the market. Since the late nineteenth century, single young Italian women migrated seasonally to France to find work as domestic servants and wet nurses, often striking out on their own to work abroad.7 In fin-de-siècle Paris, Italian and Eastern European Jewish women engaged primarily in the confection trades, participating in family-owned and -operated workshops that were often run directly out of their homes.8 By the interwar years, the most successful immigrants, including immigrant women, operated small shops, restaurants, bars, and débits throughout the Seine Department.9 On the whole, however, it was more likely for immigrant women to cluster in confection trades, textile industries, and domestic service—in short, those jobs that were low skill, low status, and low paying.10

While so-called free labor market forces confined immigrant women to jobs in confection and domestic service, the war inaugurated for them, too, a new era of state- and employer-controlled labor migration. Unlike immigrant men, however, foreign women were more often channeled directly into the agricultural sector by French employers, a funneling that must be set against the background of shifting rural and urban demographics in France throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Early twentieth-century contemporaries bemoaned “l’exode rural,” or the migration of French peasants from the provinces to large urban cities and some found the loss of paysannes from the rural workforce particularly lamentable. Like many Third Republican Frenchmen, Michel Augé-Laribé (secretary-general of the Confédération Nationale des Associations Agricoles in 1925) admired the hardy paysanne, praising her “energy,” “stoicism,” and “professional aptitude” in executing “the punishing tasks” required by rural life.11 Sadly, according to Laribé, her centuries of accumulated wisdom was now in danger of being lost forever as she left the rural hearth for factory work in the cities during the war. “Removing from the countryside women who were accustomed to living there,” Augé-Laribé chided no one in particular, “was to compromise for many years the resumption of agricultural activity in France.”12 From the war years onward, French employers sought to fill the labor void left behind by French peasant women with foreign women.

Figure 1.1.“The Great Transportation Networks Used by Immigrants in France.” Georges Mauco, Les Étrangers en France: leur r ôle dans l’activit!é économique. Avec. 100 cartes ou graphiques dans le texte et 16 planches de photographies hors texte. Paris: Armand Colin, 1932, 124.

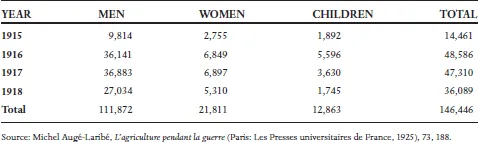

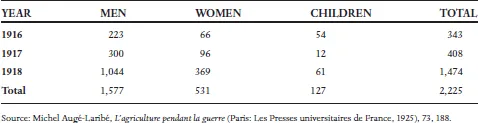

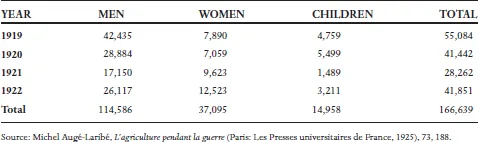

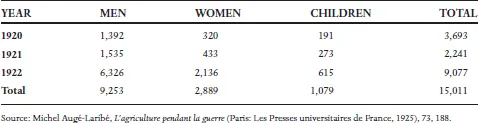

The French state, employers, and foreign labor recruitment services worked in concert to replenish the rural workforce with immigrant women and their families. Since the early 1900s, Polish families had been imported to agricultural and coal-mining areas throughout France to replace native French families, and in the early twentieth century Polish communities sprouted up in the northern, eastern, and central regions of the country.13 During the war, employers ramped up these efforts to introduce foreign families into agricultural and mining sectors, and in 1916 the Office National de la Main d’Oeuvre Agricole (ONMA) instituted schemes to organize the large-scale migration of Spanish and Portuguese men, women, and children (see tables 1.1 and 1.2).14 ONMA directors even resorted to poaching refugees from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Alsace Lorraine convalescing in internment camps in northern France during the war.15

Despite official efforts, French agriculture continued to experience labor shortages long after the war. Of the 3.7 million French rural workingmen mobilized during the war, 673,700 were killed and another 500,000 returned wounded and unable to undertake hard manual labor. Moreover, both Frenchmen and -women continued to migrate to large urban centers that promised more lucrative and less arduous employment.16 Consequently, employer-initiated and state-supported organizational efforts to recruit foreign workers continued throughout the 1920s. As tables 1.3 and 1.4 demonstrate, foreign women numbered prominently among those agricultural workers brought to France, representing about one-third of all Spanish, Portuguese, and Polish rural laborers. Between 1921 and 1926, 37 percent of Polish farm workers brought to France were women (29,549) as were 31 percent of Spanish, 18 percent of Italian, and 4 percent of Belgian agricultural workers.17

Table 1.1Spanish and Portuguese agricultural workers in France, 1915–18

Table 1.2Italian agricultural workers in France, 1916–18

While the introduction of foreign women into the agricultural sector certainly met the gendered labor needs of the French economy, employers had yet another objective in mind. Employers sought not just immigrant women, but immigrant wives, to stabilize, settle, and even assimilate their unruly menfolk. Moreover, employers’ efforts to re-create foreign families on French soil were also meant to protect foreign women from the perils of an alien environment that left them socially, culturally, and even sexually vulnerable without the protection—and supervision—of family members and husbands, especially. The introduction of foreign workingwomen into French agriculture solved three problems: it nestled immigrant women securely within families, and it put an end to what was perceived as the mobile ways of immigrant bachelors, all while meeting the persistent labor demands of France’s hardest hit sector—agriculture. But before continuing, we must first get a sense of what male continental mobility was truly like during this period and, thus, from whence these fears came.

Table 1.3Spanish and Portuguese agricultural workers in France, 1919–22

Table 1.4Polish agricultural workers in France, 1920–22

The War and Wanderers

The Great War drew soldiering men from every corner of Europe and beyond, distributing them indiscriminately throughout—the purest manifestation of the greater continentwide “mixing” of populations described here. And when the war came to an end, some found themselves quite a long way from home with little desire to return. Nicolas Goata was twenty-five years old when he first took up arms to fight for his native Romania. The year was 1913 and the war was unraveling in the Balkans. One year later, he was sent to fight “the Second European War,” as he called it. During that First World War (as we call it), Goata was taken prisoner by the Germans whom he eventually evaded, escaping to France in 1917. Fifteen years later, well after his marriage to Emilienne Authemet, he described his situation to a French official very plainly and with just a hint of frustration: “I did not come to Paris for pleasure, Monsieur. It was the war.”18

For a great many like Nicolas Goata, war and its penumbral events set them on their crooked paths to Paris. It was a meandering fate shared by a generation of men, a fate encapsulated in literary form by novelist Joseph Roth, a former Austrian soldier himself. In his 1924 novel Hotel Savoy, Roth described how the Great War had made of the average man “a soldier, a murderer, a man almost murdered, a man resurrected, a prisoner, a wanderer.”19 Through the central character of Gabriel Dan, a POW who had fought in the Austro-Hungarian Army before returning after years of imprisonment in Siberia, Roth conveyed the enormity of the task facing soldiers as they demobilized. After years of warfare and imprisonment, many men w...