1

The Intimate Life of the Nation

Reading The Second Sex in 1949

The human condition is one thing; the condition of women is another—worse. Everyone agrees on this, more or less.

Dominique Aury, review of The Second Sex, 1950.

Almost all of readers’ letters from the time when The Second Sex was first published have been lost. It is important nonetheless to reconstruct how the public was introduced to what is now Beauvoir’s most famous work. This chapter and the one that follows do so by reconsidering the critical reception of The Second Sex in that first moment. Reviewers and critics saw themselves as custodians of literary standards and public taste as well as those who set the agenda for national discussion. They held very firm, and often contrasting, views concerning the broader reading public. Those views provide new ways to understand Beauvoir’s arguments and the expectations that took shape around her.1

The matter of the reception in 1949 has been distorted by our view of Beauvoir as a pioneer ahead of her time. That assessment is meant to be appreciative, underscoring Beauvoir’s boldness and acknowledging the difficulty of such an ambitious text. The Second Sex was what French students colloquially call a pavé (cobblestone, or massive text): eight hundred pages of challenging philosophical argument, literary criticism, history, social science, and startlingly detailed description of sexual and bodily experience. It offered, first, an agenda-setting topic: a philosophical reconsideration of the female condition, or situation; second, an argument, that woman was defined as the Other of man, particular, and subordinate; and third a genre of writing that was at once authoritative, Olympian, and interior. The Second Sex was a lot to contend with. The ahead-of-its-time narrative, however, fast-forwards to the 1970s, when The Second Sex became a feminist classic, as if Beauvoir addressed only one subject and one yet-to-emerge constituency. That story ignores the many ramifications of Beauvoir’s work and obscures how The Second Sex actually landed when it came out.2 The controversies, debates, and preoccupations of the moment shaped the dialogue around the book and Beauvoir’s image.

In France, women’s suffrage had been granted in 1944, late by nearly any standard, and only after an excruciatingly long impasse on the subject was broken by a decree, issued by General Charles de Gaulle’s French government in exile under pressure from its allies. Women’s suffrage was more of an anticlimax than a turning point or cause for celebration. The sting of France’s defeat in 1940 and Nazi Occupation, and above all the humiliation of the Vichy government’s collaboration with Hitler’s regime (1940–1944), were very fresh. France’s geopolitical position had plummeted. Tensions of empire, created by anticolonial revolt and colonial repression, were readily apparent. Within France, acute material shortages, trafficking in counterfeit food-rationing tickets, and the terms of economic and political reconstruction were urgent matters. Shortages and strikes fractured governing coalitions at home. The escalating Cold War polarized international and domestic politics. In the face of this crisis and an acrimonious debate over a painful past, postwar intellectuals in France sought to project forward—“to recover the future,” as Sartre declared.3

Beauvoir’s tone captured that determination. In the first paragraph of The Second Sex, Beauvoir writes as if she is pushing aside the clutter of books and papers on her desk to clear her mind and start over:

For a long time, I hesitated to write a book on the woman. The subject is irritating, especially to women; and it is not new. Enough ink has been spilled on the quarrel of feminism, and it is now practically over. We should say no more about it. It is still talked about, however. And the voluminous nonsense uttered during the last century seems to have done little to illuminate the problem. After all, is there a problem? And if so, what is it? Are there women, really?4

Beauvoir’s intellectual clearing of the decks called for rethinking the very starting point: “woman” or “femininity.” She conceived womanhood in existential and phenomenological terms—as a “condition,” “lived experience,” or, perhaps most effectively, a dynamic process of becoming. “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”5

Beauvoir positioned herself as a woman in a new generation of intellectuals, impatient with past discussions. She bridled at the “voluminous nonsense” written about women. She sharply distanced herself from models of political actions by women. “We are no longer like our partisan elders,” she writes a few pages into the introduction. “By and large we have won the game … Many problems appear to us to be more pressing than those which concern us in particular.” She believed that feminism offered only a narrow and reformist politics, which paled by comparison with the other movements that were changing the postwar world: “Women do not say ‘We,’ except at some congress of feminist or similar formal demonstration … The proletarians have accomplished the revolution in Russia, the blacks in Haiti, the Indo-Chinese are battling for it in Indo-China; but the women’s effort has never been anything more than a symbolic agitation. They have gained only what men have been willing to grant; they have taken nothing, they have only received.”6 In its urgency, its disavowal of bourgeois feminism, its attentiveness to civil rights and anticolonialism, and its insistence on recasting a humanism for the future while also reconceiving the humanity of women, The Second Sex was very much a book of postwar France.

The Second Sex did not meet with silence. The historian Sylvie Chaperon has detailed the scandal and mud-slinging the book and its author encountered. Some of the furor arose from the deep political divides in the French cultural world. Beauvoir and Sartre’s radicalism provoked conservative rage, but their determination to remain nonaligned in what was becoming a cold war of the intellectuals made them targets of communist scorn. The Second Sex became a proxy war in this conflict.7 Parts of the book were also shocking, opaque, or both. The issues that critics raised in 1949, especially the boundaries of public discussion and the conceptions of decency and modesty that mapped those boundaries, would resurface repeatedly in the decades that followed. Those conceptions did not apply only to matters of sex; they reached broadly into what we might call the intimate history of the nation.8 The feelings roused in these discussions would also infuse letters from readers.

Critics often wrote remarkably personally. They claimed to imagine vividly the public’s conversations about The Second Sex. Depending on their position in the landscape of postwar journalism and critical thought, they offered very different conceptions of what that public would—or should—accept.9 I examine three different and important sites on that postwar landscape. First up is the newly founded (1949) Paris Match, a magazine that resembled the American Life. Paris Match published long excerpts from The Second Sex in some of its first issues. Its editors expressed confidence their readers would welcome Beauvoir’s bold provocations. The second is Les Temps Modernes, also newly founded, with Sartre and Beauvoir at the editorial helm. A small, radical, and intellectual journal, it had a far edgier notion of what provocative meant. The third site is the literary supplement of the oldest daily newspaper Le Figaro. There, the distinguished Catholic writer François Mauriac, casting himself as the defender of French literature and the nation’s reputation, mobilized an all-out attack on existentialism and associated enemies. Mauriac spoke on behalf of a public that he believed to be dismayed by the book’s obscenity, self-revelation, and prurience. Over the next two years, first in a forum organized by Mauriac and then individually in different journals, scores of critics from different positions in the cultural world would try to summarize and assess The Second Sex, bringing Beauvoir’s arguments into conversations they believed the nation and their readers needed to have. The way these reviewers presented The Second Sex, wove Beauvoir’s arguments into their intellectual agendas, and wrestled with the powerful feelings she aroused dispels the generalization that Catholic France was shocked. It provides a much fuller sense of the culture and politics of this postwar moment. It outlines the public’s expectations of intellectuals—and intellectuals’ expectations of their followers.

Paris Match

The Second Sex came out in stages.10 When the first volume was published in June 1949, Paris Match took notice. On August 6, 1949, the magazine published an issue with long excerpts from that volume. A red banner across the magazine’s cover announced simply, “La femme, cette inconnue.” “The Woman, This Unknown” is less dramatic than the wording in French, where the “this” conjures up a figure or region that is unexplored or mysterious, playing with the clichés of the enigma of the feminine or Freud’s reference to the “dark continent” of women’s sexuality. According to Paris Match, Beauvoir herself had chosen this heading, perhaps to pique interest in her critique of these myths. “What is woman?” The Second Sex asks. The answer leads the reader from a discussion of “the data of biology” and the meanings attached to sexual difference to a critique of psychological, social, and literary portraits of the feminine. Along the way, knowledge that is scientific, verified, or common sense is shown to be socially constructed and mystified. There is no essence of femininity, Beauvoir argues in volume one. Instead there is only the rich facticity of the female body and an equally rich constellation of myths that cast the woman as Other, shaping experience and female consciousness and subjectivity.

Right below the banner announcing Beauvoir’s book, Paris Match placed a cover photograph of the French screen idol Henri Vidal posed, Rock Hudson–like—his chest, chest hair, and nipples showing through a fishnet T-shirt.11 Vidal was an icon of male sexiness, a former body-builder and star of six films, almost all of which featured his athletic torso. In the just released film Fabiola (1949), Vidal played a young, handsome, secretly Christian gladiator in a drama about the crumbling Roman Empire, whose rulers blame Christian minorities for its decline. He is denounced and sentenced to die, but fights back against his persecutors in the gladiators’ arena. The analogy to Nazi persecutions and heroic resistance was obvious. It was also politically palatable: cheering for a persecuted Christian minority required no hard thinking or self-scrutiny about anti-Semitism. Vidal’s photo and the film are reminders of the lurking presence of World War II in the background of discussions of The Second Sex in 1949.

Paris Match was a landmark in the new world of the postwar French press. It had launched just a few months earlier, in March 1949. Its owner, Jean Prouvost, already a well-known press magnate in the interwar period, was tainted by charges of working too closely with the collaborationist Vichy government. As part of getting a new authorization to publish, Prouvost overhauled Match, the sporting magazine he already owned, and turned it into something modeled on the American magazine Life.12 At Paris Match, “the image ruled.” But the magazine also cared about words and often featured writers in its pages. It aimed to cover “current events” (actualités) and provide its readers with “eyes and ears on the world.”13 A bracing modernity was thus part of its pitch to readers, and its August 6, 1949, cover is a good indication of how it imagined the readers it sought to reach. Pairing the writing of Simone de Beauvoir, whom Paris Match called “the first female philosopher in history,”14 with Vidal’s visible and sexy male body, the magazine addressed its audience as curious, intelligent readers who were ready, after the war’s horrors and in the face of a painful and slow recovery, to be awakened.

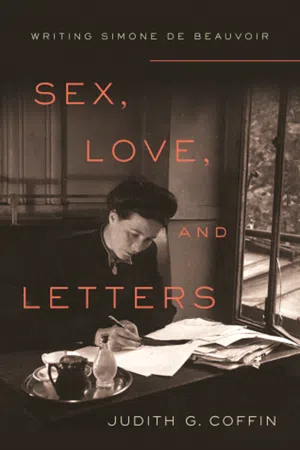

Inside that August issue, Paris Match introduced Beauvoir and published excerpts from volume one of The Second Sex. The introduction (unsigned) said what one might expect from a magazine that covered current events and cultural and political celebrities. Beauvoir was beautiful, with an “austere and serene face”—“a rest for weary eyes.” She spurned high fashion, bought inexpensive dresses in Portugal, and owned one coat, which she had brought back from her recent trip to the United States. She had “learned to read in a private school on the Left Bank of Paris” and “learned to think at the Sorbonne.” And learned she had, for she passed the agrégation, or docto...