This is a test

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The world of healthcare is constantly evolving, ever increasing in complexity, costs, and stakeholders, and presenting huge challenges to policy making, decision making and system design. In Design for Care, we'll show how service and information designers can work with practice professionals and patients/advocates to make a positive difference in healthcare.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Design for Care by Peter Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Rethinking Care and Its Consumers

The rapid diffusion of hundreds of Web resources for health purposes has created a gap between information quality and user expectations. Consumers can now pursue their own research into health issues by searching the vast collections of consumer-oriented health information on the Web. They cannot be expected to understand the complexity of health issues, but do expect health information to be truthful. Yet more information does not yield better information. In fact, quite the opposite may be true. Part I focuses on the health-seeking activities of the healthcare consumer.

Health-Seeking Experiences

A person’s health seeking is a continuous process of taking steps toward better health—before, during, and after any type of encounter with traditional healthcare service. Health seeking, as with other human motivations such as pleasure seeking or status seeking, represents an individual journey, in this case toward relatively better health. For a very healthy person, the ideal of perfect fitness may be an authentic health-seeking journey. For a cancer sufferer, relative health may be a matter of surviving treatment and fighting for gains in remission. These are health-seeking behaviors with quite different personal struggles, achievements, care needs, and support requirements. Seeking health covers a set of fundamental human needs. Every person is a health seeker in their own way, even if not a “patient” or a fitness buff.

A person’s progress in health seeking is measured by points of feedback sensed from their everyday lives and received from professionals. People with chronic health concerns such as diabetes need continuous feedback. Those in “normal” health may find health feedback only marginally helpful. (For example, I may measure my workout progress, but I weigh myself on a scale maybe only twice a year.)

People also have different timeframes of health feedback. Think of the health-seeking journey as occurring over a lifetime, a continuity that proceeds through youth, adulthood, and older age. The individual and his or her immediate circle of care (spouse or partner, family, friends) are co–health seekers in many ways (though never “co-patients”). Everyone travels this journey together with parents, children, friends. The health journey includes a lifetime of other encounters and experiences that can enhance responsible healthy behaviors.

Yet healthcare providers have little insight into the continuous health-seeking journey. Although doctors may see dozens of individual “cases” on any given day, they have little time and usually no formal payment mechanism to follow an individual’s health journey after a professional medical encounter. Their brief touchpoint is but one opportunity for improving an individual’s health among dozens in a given day. There are certainly different types of practices, and some do track and manage longitudinal health outcomes. Yet an individual’s health seeking is his or her own journey.

For more than a century, Western healthcare has treated people as patients, as passengers in a complicated and mysterious train on rails governed by seemingly unknowable biological forces. Any degree of pathology is relative to a normal (“healthy”) standard and to a person’s own experience, which may be unknowably limited and limiting. The normal condition is one of relatively balanced health in a constant motion toward homeostasis. When facing conditions that require medical intervention, people are motivated to seek health as an end in itself, as well as supporting all other goals in life.

Clinicians might find the current mandate to improve the patient experience as the perfect entry point to engage design practices as full partners in providing better care. Designers have the advantage of not being doctors—they are not professionally bound to the same legal responsibility to treat people only as patients, subject to clinical intervention. By repositioning the individual health seeker as a deciding and knowing agent of his or her own experience, health services can be designed to facilitate a whole-person approach to health. Improving patient experiences is the just the first step in a cultural and historical shift. A person is a patient for a limited period, but the experience of seeking health is a continuous process throughout life. Care providers and resources can help restore natural and supported functions of life.

Health seeking is not just a “journey to normal” because there is no final state of health. People live with multiple conditions of relative health in a balancing system. Measures and indicators of “healthy” are not optimized; they are better or worse compared to an individual’s own baselines. People may lose weight by dieting but not improve cholesterol levels; they may recover from a viral infection but have a cough for weeks. No health measures are static, and the numbers of good measures are not as “objectively healthy” as people might think.

Health journeys are self-educating—people evolve as they learn in stages of struggle, understanding, acceptance, and self-management. Health seeking is an evolutionary act of self-discovery, of sustainable improvements of behavior and experience that claim a personal stake in one’s present satisfaction and future thriving.

The Health Seeker in Context

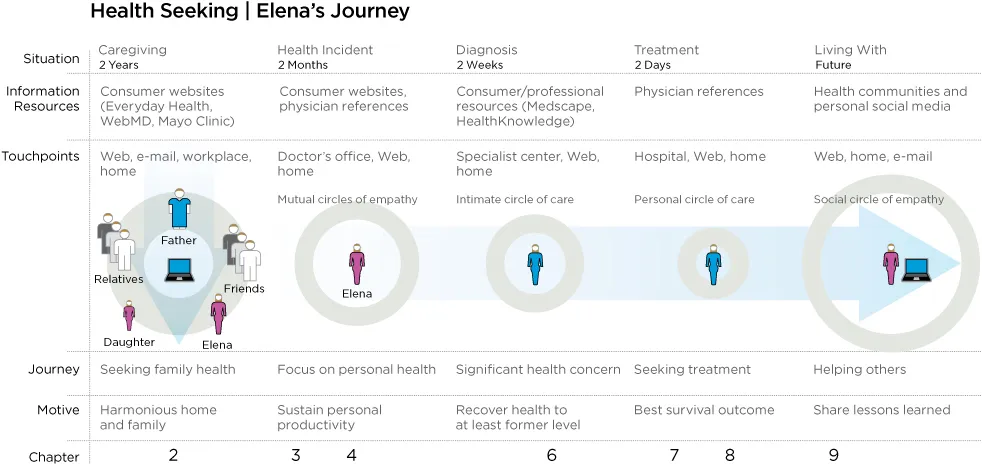

Beginning in Chapter 2, each chapter advances the scenario of a persona character, Elena, as she navigates complex health issues and pursues health outcomes over a series of setbacks and healthcare encounters. Her story serves as a baseline narrative to observe human responses to events, touchpoints, and likely decisions for care services. This health-seeking journey is loosely aligned with each chapter’s content.

FIGURE I.1

A health seeker’s journey.

A health seeker’s journey.

Elena’s scenario is not unlike a service journey map, except from the perspective of the health seeker, whose shifts in role and identity are based on health condition and goals. The journey map is based on a typical method for portraying the navigation of health seeking and clinical encounters (Figure I.1). Notice that over the entire span of roughly two years, significant health events happen in brief intervals of two months or less, with significant impact on future health and life outcomes.

Physiological measures indicating relative health are not shown on this timeline, but are suggested in other contexts to indicate correspondences between measures, acute incidents, and recovery. Design goals for the health seeker in this journey view might include:

• Connecting Elena to her immediate family to support her caregiver role (through electronic media, printed artifacts such as notes and reminders, and multisensory media).

• Giving her direct support to inform and manage her family’s health needs, and connecting her with any services for which she has regular touchpoints.

• Providing her with emotional support as a caregiver to help sustain her motivation and keep track of health progress.

• Enabling her to easily update and track her interactions with clinical services and healthcare systems.

Part I, with its focus on consumer contexts, describes Elena’s personal sphere as she seeks information, support, and resources from her immediate circle of family and community to meet her health goals. Part II describes her choices and outcomes experienced as a healthcare patient, and Part III shows her as a participant in the healthcare system.

CHAPTER 1

Design as Caregiving

Can Healthcare Innovate Itself? | 8 |

Are There Users of Care? | 12 |

A Caring Design Ethic | 15 |

The Design Thinking Divide | 17 |

Wicked Problems in Healthcare Design | 21 |

Can Healthcare Innovate Itself?

Whether you choose a story from your own life experience or from that of a friend or family member, or just Google “healthcare horror stories,” the problems in healthcare today are clear and all too common. Urban emergency rooms are overflowing, medical devices have misleading interfaces that lead to errors, doctors order too many expensive and unnecessary tests, and medical records are confusing and unreadable. Private health insurance is complex, expensive, and fragmented, sometimes resulting in crippling financial difficulties. Pharmaceutical wonder drugs are pulled off the market after a few years as emerging harmful side effects show up. Healthcare has optimized every function in the system, but the system grows more complex as these functions overlap and compete. As Harvard management professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter recently wrote,

Supposedly, everyone working in health care wants the same thing: to help people get and stay healthy. . . . The problem is that everyone can have a different view of the meaning of getting and staying healthy. Lack of consensus among players in a complex system is one of the biggest barriers to innovation. One subgroup’s innovation is another subgroup’s loss of control.1

Because healthcare problems are so complicated and messy, they cannot easily be untangled once they appear. Mike McCallister, CEO of insurance provider Humana, described the US healthcare sector as a gigantic mix of varied players that is “broken, but can be fixed. We don’t actually have a healthcare system. We have a lot of different systems that are glued together.”2 Alex Jadad, founder of Toronto’s Centre for Global eHealth Innovation, calls for immediate innovation in person-centered healthcare and collaborative development of IT to help Canada’s high-functioning but stressed healthcare system: “This technology can help us transcend our cognitive, physical, institutional, geographical, cultural, linguistic, and historical boundaries. Or it can contribute to our extinction.”3

Designing for care brings a holistic and systemic design perspective to the complex problems of healthcare. We are already improving services by designing better artifacts, communications, and environments. What remains missing is the mindset of professional care in designing for people, practitioners, and societies. Like clinicians, designers in the health field can take responsibility for helping people and societies become healthier in all aspects of living.

Technology Will Not Save Healthcare

Technologists advocate for disruptive innovation in healthcare, a call that envisions radical change for consumers as well as the largest institutions. The two targets of disruption are typically hospital-based institutional healthcare and the medical care model itself. The cure is envisioned to be a future of low-cost networked computer technology owned by consumers, not clinicians. A kit can be imagined consisting of embedded sensors connected to a handset, cloud-based data collection with instant analytics, and continuous-learning algorithms that diagnose individual conditions based on rapid sensor tests and genetic analysis. Possible new treatments are not described clearly, but still an accountable person will be needed to administer injections and judge the appropriate therapy and medications. A problem with such scenarios is that they project a future driven by technological determinism—because it can be done, it will be done.

The decentralized “future of medicine” scenarios articulate radical changes in technology but fail to address changes in cultural meaning. As pictured by Silicon Valley, healthcare could be decentralized and fragmented into defined care streams that the “user” (the patient) would navigate as self-service interfaces. In effect, these scenarios shift care decisions to “consumers” who might be existentially vulnerable to their own poor decisions (as well as to new types of usability risks). If patients are forced by economic changes to trust a technology instead of a physician, the ethics of “brave new healthcare” scenarios become socially problematic.

The technologically determined scenarios suggest a sociological change more radical than any other system designed in human society. Healthcare is the world’s largest employment base, with national health systems among the largest employers in their respective countries. Such a disruption would ignore the sociotechnical foundation of healthcare that underlies practice, education, policy, employment, and the very meaning of care. It risks replacing medicine with a new corporate system devoid of human socioculture or caring, treating diseases as functional states mediated by robots. Although the enabling technologies can and will be...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- DEDICATION

- HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

- FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

- CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I Rethinking Care and Its Consumers

- PART II Rethinking Patients

- PART III Rethinking Care Systems

- References

- Index

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- Footnotes