eBook - ePub

Voices on War and Genocide

Personal Accounts of Violence in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe

This is a test

- 520 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Voices on War and Genocide

Personal Accounts of Violence in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Taking as its point of departure Omer Bartov's acclaimed Anatomy of a Genocide, this volume brings together previously unknown accounts by three individuals from Buczacz. These rare narratives give personal glimpses into daily life in unsettled times: a Polish headmaster during World War I, a Ukrainian teacher and witness to both Soviet and German rule, and a Jewish radio technician, genocide survivor, and member of the Polish resistance. Together, they offer a prismatic perspective on a world remote from our own that nonetheless helps us understand how people not unlike ourselves responded to mass violence and destruction.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Voices on War and Genocide by Omer Bartov in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE ACCOUNTS

ANTONI SIEWIŃSKI

MEMORIES OF BUCZACZ AND JAZŁOWIEC DURING THE GREAT WAR, 1914–20

Part I

As soon as the world war broke out, I began writing and taking note of everything that occurred in the city of Buczacz and its environs. These notes were written very tightly on about forty sheets of paper. When the Muscovites1 combed through all the houses [before they withdrew from Buczacz] in May 1915, seeking to grab all valuables and precious metals they could lay their hands on, I regrettably threw these notes into the oven and burned them, fearful that if they were found I would suffer the consequences. Since these entries clearly indicated the abuses carried out by the Russian army, and especially by Muscovite civil servants, had they fallen into their hands they would have surely hanged me.

And so, I rewrote these notes and sent them in 1915 to the editor of the newspaper Słowo Polskie [“The Polish Word,” a newspaper published in Lwów (German: Lemberg; Ukrainian: Lviv), 155 km northwest of Buczacz], yet as I later found out, they never reached their destination but were confiscated by the Austrian authorities in Stanisławów [70 km southwest of Buczacz]. Rather than being forwarded they were lost in the officers’ casino. Again, I was not deterred and wrote these memoirs for a third time, taking them all the way to the end of the world war and further to the peace treaty [of Poland] with the Russians in 1920.

I wrote these memoirs for my sons in remembrance of the city in which they had spent their youth and school years, as well as for friends and acquaintances from Jazłowiec [17 km south of Buczacz]. Now that the war is over, I have already forgotten many events; my imagination and memory have weakened, and like many other Poles a great deal has changed for me. I still regret having lost my earlier notes. All four of my sons took part in the war; if they wish, they can expand these notes and presumably write a hundred-fold more than I have written in these memoirs and perhaps also correct this or that point.

Buczacz is a little town whose prewar population numbered fourteen thousand people. It stretches along the Strypa River, which descends into a little waterfall below the church. The city was founded in the fourteenth century by the Turowski clan, who later took up the name Buczacki, since there were many beech forests in the area.2 Unfortunately these forests no longer exist today. In the valleys all the trees were felled. [… And now] the city is surrounded by forests, in which birch, oak, and other trees grow, all apart from beeches. Three kilometers away are the ruins of a so-called cloister. In the past there was a church and some kind of monastery there. And right next to these ruins flows a stream that eventually runs to a waterfall. When the sun shines the drops form a rainbow. In Buczacz people relate that at the time of the Tatars the monastery was plundered and burned down, and all of its forty inhabitants were murdered.

The Potocki clan inherited Buczacz [in 1612] and remained there ever since. … The cities of Buczacz, Jazłowiec, Trembowla, and Kamieniec Podolski [17 km southeast, 48 km northeast, and 115 km southeast of Buczacz, respectively] were once border posts that protected Poland. They were held by knights who watched over the entire region with eagle eyes, so that no enemy could come close to these cities; and if the Tatars or other enemies approached, the knights would repel them and take booty. By the Strypa, overlooking a huge gorge, a vast castle once stood, of which only ruins are left. The walls of this castle withstood the Turkish and Tatar hordes.

After Kamieniec Podolski was captured by the Turks, the Sultan Mehmet IV came to Buczacz [in 1672] and signed the peace of shame with Poland next to the linden tree that still stands there today, in which Poland conceded Podolia and Ukraine to the Turks and agreed to pay a penalty of 22,000 ducats.3 But God sent the courageous hero [King Jan III] Sobieski to the Poles, who refused to implement this treaty and dealt such a defeat to the Turks, that they abandoned the region and kept only Kamieniec Podolski. In Kolejowa [Railroad] Street, also known as Potocki Street, there is a fountain that was named after Jan Sobieski. Legend tells that King Sobieski drank from this fountain.

During the partition of Poland in 1772 [Austrian Empress] Maria Theresa, fearing an uprising by the Poles, ordered all castles destroyed in Lesser Poland [the annexed southeastern lands renamed Galicia by Austria], with the exception of the castles of Żółkiew, Olesko, and Podhorcy [125 to 185 km northwest of Buczacz], in remembrance of the fact that these castles had belonged to King Sobieski—which, to my mind, is a beautiful gesture of gratitude! For had the Poles not helped out at the time of the siege of Vienna [by the Ottomans] in 1683, there would have been no Austria. Yet ninety-one [should be eighty-nine] years later the greedy clan of Habsburg, instead of helping Poland, exposed its claws and annexed the entire southern part of Poland. At that time the castle of Buczacz was also demolished. …

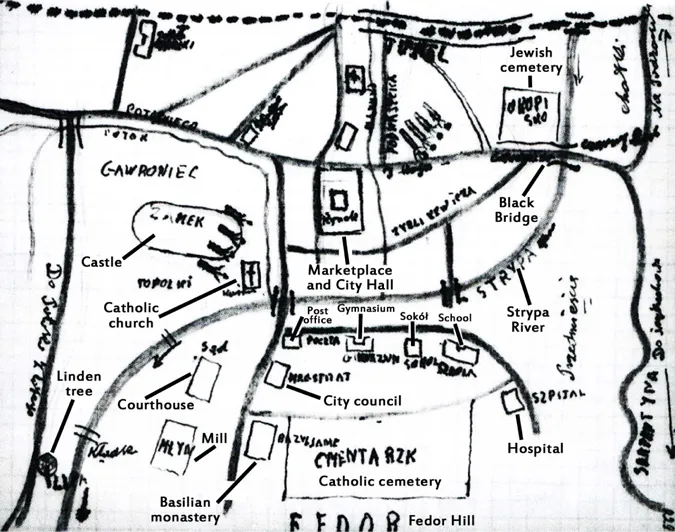

Map 1.1 Hand-drawn map of Buczacz in Antoni Siewinski’s diary, ca. 1922.

The city jewel is the town hall, whose construction was funded by [Polish magnate and city owner] Mikołaj Potocki [1712–82]. He also built the monastery of the Basilian [Greek Catholic order] monks, large churches, the [Roman Catholic] parish church and the synagogue.4 Additionally, Mikołaj Potocki was appointed administrator of Kamieniec, and people say that he was also a jolly man and a bon vivant. Many of these stories were invented by bad and foolish people without honor; the churches and cloisters that Potocki built not only in Buczacz but throughout Eastern Lesser Poland demonstrate that Potocki was a great patriot and man of honor.5

In the city there are two schools, which were built in 1904. Each of these school buildings has over twenty classrooms and accommodations for the principals. There is also a large building, the gymnasium, from which brave men and good patriots graduate. Before the war the city had 8,000 Jews, 3,000 Poles, and 3,000 Ruthenians. The girls’ school was attended by 750 Jews and 350 Catholics.6 In my [boys’] school [where Siewiński was the principal] there were 180 Jews and 120 Catholics. Now, in the immediate aftermath of the war, this relationship has changed somewhat, so that in 1922 there were 154 Catholics and only 70 Jews in my school.

Having been rebuilt after a fire [in 1865], the city had beautiful houses and stone buildings filled with wares; it had the largest warehouses in all of Podolia. In these stores there were vast supplies of fabrics, linens, clothing, ironware, furniture, food items, and so forth. All of this was Jewish property. The Poles and Ruthenians also owned houses, but they were in the outskirts; the Catholic population was engaged in craftsmanship, such as locksmiths, forgers, builders, tailors, furriers, and in the more distant outskirts they worked on the land. The women planted maize and other vegetables in the gardens.

The town had always had a Jewish mayor. For thirty-six years Mayor Bernard Stern ruled the city.7 He was an interesting man, keen on eating, even more so on drinking, but he never became a drunk; he liked playing cards, although he almost always lost. The city officials were all Jews, except for the Catholic Zatarnowski. In the gymnasium too there were Jewish teachers, as well as in the general-education schools. Now everyone makes mistakes, but whenever a Jew did something wrong, and a Catholic pointed this out to him, the Catholic would immediately be accused of antisemitism and come into many difficulties. That is to say that the Jews, even the most honest among them, could always take revenge, and then hide behind the claim that the Catholic was at fault and say, “we are innocent,” although anyone could see that the Jews were behind it. Well, nothing could be done about that, since Jewish religion postulates: “An eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

While I do know some honest and honorable Jews, the exception only proves the rule. The Jews care a great deal about schooling, they educate their children, send them to elementary school, middle school, and to the gymnasium, and as an old and experienced teacher I can say that the Jews are good students. The [Christian] citizens care much less about education. Before the war there were many watering holes here, in which people drank in the evenings and on holidays, so that eventually the Catholics drank away the entire inner city, while the Jews became the owners of the most beautiful houses in town: who is to be blamed for that?

But enough with this description of what is now a completely dilapidated and ruined city; let me get down to the main issue at hand. …

The opening of hostilities came sooner than expected. On 28 June 1914 the Serb Gavrilo Princip8 shot the Austrian heir presumptive and his wife. When the news reached Buczacz, the first thing I said was: “This murder will result in great bloodshed.” And that is precisely what happened. … But I do not want to speak about politics, because there are others who can express themselves on this topic at greater length and depth. What concerns me primarily is to write my memoirs for my three [living] sons, as well as for my friends, who may read them at some point.9

At the beginning of the war I had four sons. The two older ones [Józef and Zygmunt] had already gone to university; the third, Marian, was seventeen years old and a student in the 7th grade; the youngest [Roman] was only fourteen and had just graduated from the local gymnasium.10 Living with us was also a cousin, fourteen-year-old Stefania Gruszyńska, a very good and lovely young woman, whom we raised. The eldest son, Józef, had been called up for military service and would have volunteered in the fall. He was riding his bicycle in the direction of Hungary when the news arrived that Austria had declared war on Serbia. Having been enlisted, he had to return right away in order to report to the army. In-between we received increasingly bad news, namely, that war had broken out with Russia, France, and Belgium. The Prussians11 invaded and without paying attention to international law occupied Belgium and were marching on French soil.

In Buczacz mobilization was announced. Thousands of older and younger men were called to arms. Whole trainloads of recruits passed through Buczacz on the way to the West. One could detect no signs of worry on these people’s faces: “On to the Muscovites!” they all called out. Everyone thought that in three months the entire Muscovite state would be vanquished, and the war would be over.

Then we received some remarkable news. A certain formerly unknown Józef Piłsudski12 had put together a military formation called the Polish Legion and had crossed the border into Congress Poland,13 where it defeated the Muscovites and occupied the city of Kielce. News of this spread like wildfire and inspired the souls of Polish youth. Józef had already presented himself to the Austrian army in Stanisławów; the younger two, Zygmunt and Marian, prepared to join the Polish Legion along with another two hundred youths from Buczacz and its environs. These included students, craftsmen, and peasants from the villages.

Some of the adults wanted to hold the youth back, since they thought the mobilization was an error. The members of the local [nationalist gymnastics] Sokół [Falcon] Association had a similar attitude. During calmer times, they had all sung patriotic songs, but now, when the moment had come to take up arms, none of them was seen and no one showed up to lead the youth. Nowadays [1922] they want to have their say in politics, but at the time, when the Fatherland had to be defended, they could not be found.

At the lead of the Buczacz formation stood Władek Winiarski (now a lieutenant), a student of the 7th grade in the gymnasium, a courageous youth who knew his way in the world. All the others obeyed his orders—students, craftsmen, peasants, everyone, including academics, Riflemen and members of other associations.14 The members of the Sokół Gymnastics Association had called the youths of the Riflemen’s Association cowards, but now the latter were about to demonstrate who had greater love for the Fatherland.

News came that the Austrians had already taken Kamieniec Podolski and were pushing further into Muscovite areas, and that Belgrade had been taken; it was also reported that the Prussians had crushed Belgium and were now advancing on to Paris, and that the Russians in Congress Poland had been defeated. In one word—only victories! There were also skeptics who did not believe any of this news. There were rumors about how many men from Lwów had fallen in Belgrade, that the entire 30th Lwów Brigade had been wiped out there; and, that the Muscovites had amassed powerful formations and were advancing toward Galicia with an army of five million men.

It was also said that the Austrians did not want to share the fate of Napoleon I and Charles XII,15 and instead would lure the Muscovites into Galicia in order to encircle them there. The greatest battle was expected in Niżniów on the Dniester [40 km southwest of Buczacz], where the Russian army was to be defeated. After all, as early as 1912 the supreme commander of the Austrian army, [Field Marshal Franz Conrad von] Hötzendorf, had come to Buczacz with his entire staff and remained here for several days, in order to explore the area and to forge war plans. Hötzendorf was considered a brave soldier and seen as equal to Napoleon I.

Winiarski ordered his formation to undertake military training in the Buczacz district. The formation included also several older people, especially schoolteachers, who did the right thing by joining. But they believed it would be easy to participate in long, strenuous marches; they hurt their feet and had to recognize that while the spirit was strong, the flesh was weak. After five days only those youngsters remained who had a strong will and stamina.

On 18 August 1914, Emperor Franz Josef I’s [84th] birthday, Mayor Stern invited a Jewish choir to sing imperial hymns on the streets of Buczacz. As is usual on such occasions, mostly Jews assembled on the street and made tremendous noise, with the music alternating between “Kołomyja” and “Krakowiaczek.”16 They held up a portrait of the emperor and the mayor made a speech to the crowd: “What was the Serb thinking? We will show him, what a real emperor is! Today we give Belgrade to our emperor! Long live our illustrious master!” “Long live, hurrah!” yelled the crowd. Then someone suddenly called out: “Long live linoleum! Long live, hurrah!” “Who called out linoleum?” the mayor shouted back. But although they looked for the joker, he could not be found in the crowd.

Thereafter they marched down May Third Street17 to the Kachkovsky reading room.18 This was a Muscophile [i.e., Russophile] reading room, where a woman and her three children were living. Suddenly stones were thrown from all sides and fragments flew everywhere, almost striking the children and their mother, who were entirely innocent and had nothing to do with politics. Thereafter the crowd wanted to march on to the Black Bridge,19 where a Muscophile boarding school was situated … but Police Inspector Stefanus sent the noisy crowd back to the marketplace. Just a year later nothing was to remain of that boarding school, a beautiful brick building, since the followers of Piłsudski took it apart to make use of the building materials.

That evening the city was wonderfully lit up. The Jews put lights in all their windows and hoisted the black-and-yellow Austrian flag. They put up posters on the walls, announcing that a meeting concerning the Jewish question would be taking place in the city council, to which all residents of the city were invited. The most distinguished representatives of the Poles and the Ukrainians received a special invitation. I was also sent such an invitation and chose to attend.

The hall was full of Jews and a few members of the Catholic intelligentsia. At the podium one kike20 was speaking. He began by reading out several phrases in Aramaic [likely Hebrew] from a book, and then went on to make a speech in this language. He was followed by some attorney, called Eisenberg, who spoke in Polish, and addressed the Poles and the Ruthenians, asking them to help the Jews achieve equal status, so that they too would be able to establish their own [paramilitary] legions and fight the Russians alongside the Polish legions and the Ruthenians in order to defend the Fatherland together. This speech betrayed the speaker’s fear of the Muscovite hordes, since he spoke about that many times.

He was answered by Mr. [Józef] Chlebek, a gymnasium teacher, who remarked that the Jews had never had it badly in Poland, as can best be seen from the fact that when they fled persecution [in the Middle Ages] throughout Europe the Jews found refuge, protection, and a living in Poland, so that today the Jews are the richest group in Poland. Since they are in Poland, they should also think like Poles and feel like Poles despite their Mosaic faith. The Ukrainian postal official Siyak then also spoke in a similar vein.

But the Jews wanted to prove that they could also do something. “Why can’t we establish legions?” they asked. And so, the attorney Alter assembled the entire Jewish youth and took them to the outskirts of the city, where he arranged them in columns of four rows and marched with them back to the city. I was just on my way to the district administration when I heard the sound of a trumpet coming from the [soccer] field on the Fedor [hill on the outskirts of Buczacz]: “Tratata! Tratata!” At first, I thought that these were our Polish legionnaires returning from their exercises, since they had already been away from Buczacz for five days. In the city all the inhabitants were trembling with fear that perhaps they had been snatched by the Cossacks, who had already captured Husiatyn [75 km east of Buczacz], and the Austrian troops were already on the retreat. Masses of people were fleeing from the city, on carts, ca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Abbreviations

- Note on Language, Place, and Personal Names

- Introduction

- The Accounts

- Bibliography

- Index