![]()

Part I

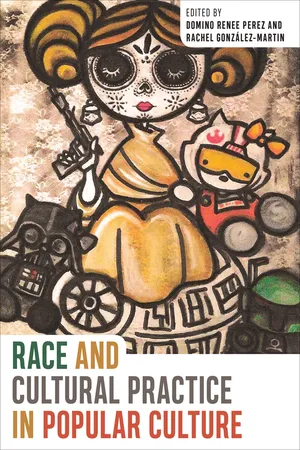

Visualizing Race

![]()

1

A Thousand “Lines of Flight”

Collective Individuation and Racial Identity in Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black and Sense8

RUTH Y. HSU

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line, the question of how far differences of race—which show themselves chiefly in the color of skin and the texture of the hair—will hereafter be made the basis of denying to over half the world the right of sharing to their utmost ability the opportunities and privileges of modern civilization.

—(DuBois)

Context: The Past in the Present

The impact of the color line in the United States is as consequential in 2017 as it was when DuBois wrote and spoke the words above. One hundred and fourteen years after those words, in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, Darren Wilson, a white police officer, fired twelve rounds at eighteen-year-old, unarmed, African American, Michael Brown, killing him. “Ferguson” became an emblem almost immediately, reflecting the deep divisions in the United States on the matter of race. And the name of the town became instantly recognizable and representative of a moment when many more white citizens of the country realized, finally—as if a light in a room had been abruptly switched on—a reality that poor, black communities had long lived, which is that black lives do not matter, that many police have used for some time lethal force in predominantly black neighborhoods as the first rather than the last resort.1 Yet, “Ferguson” did not become the irreversible tipping point of radical change for the better; while this chapter was being prepared, in what might prove to be a critical juncture for the whole of U.S. democracy, Heather Heyer, 32, was run over and killed by 20-year-old James Alex Fields, Jr., who drove into her and a group of counter-protestors demonstrating against a Unite the Right march on August 11–12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia. The assault took place on the afternoon of August 12, 2017; nineteen other counter-protestors were injured, some critically.2 The white supremacist terrorism in Charlottesville and President Trump’s succor offered to the so-called alt-right at a press conference several days after the killing of Heather Heyer are clear signs of U.S. democracy in crisis, a crisis catalyzed once again by the issue of race.3

While the most evident forms of racism might be better understood today than fifty years ago, there continue to be deep divisions in the country over the less evident, systemic nature of racism. For example, there is very little comprehension of factors leading to racial groups being drawn to live in the same neighborhoods and perhaps to struggle with what sociologists and political scientists term environmental racism. Understanding is also lacking as to why one cannot “just move out” of those neighborhoods, or why there is no equivalency between the slogan “White Lives Matter” and the movement “Black Lives Matter.” In addition, a pervasive viewpoint on racism is that its most pernicious forms have been destroyed or that it exists only in small pockets (read: black neighborhoods) of major cities. Barack Obama’s election, for instance, briefly ignited the narrative that the United States had achieved a postracial state. The various, often conflicting, understandings on race are magnified by the lack of awareness about the imbrication of gender and racial identity and how both identity categories function to organize class hierarchy and economic inequalities.

One’s awareness of how racial and gender identity intersect to bolster white supremacist, heteronormative divisions and oppressions in the United States stem from many factors, two of which are immediately germane to this examination of Orange Is the New Black (OITNB) and Sense8: (1) the extent to which race and gender matter—and the extent to which one apprehends how they matter—is a direct outcome of one’s everyday lived reality, a reality that is distilled through one’s body, its physical features, its half-life in time and space beyond the present moment; (2) in an age when social media, entertainment media, online culture, and so-called online news media constitute the vast majority of our daily lives, often, for many passive consumers of these popular cultural texts, what we are served becomes our reality. George Gerbner’s “cultivation” theory seems to be applicable to this newer media environment (Morgan and Shanahan). The reporting on Charlottesville is the most recent example of this problem: the vast majority of news reports cast the “white supremacist” march to the statue of Robert E. Lee on the University of Virginia campus as a horrible event but nonetheless an aberration, a nostalgic throwback to the bygone era of the old Confederacy on the part of a small white minority. In sharp contrast, the discursive composition, throughout the history of this nation, of the “black” body and the African American presence has always already consisted of dehumanizing the individual and the whole group; this essentializing of blackness is frequently conveyed in popular cultural texts through images of criminality and black bodies as constitutionally incapable of self-discipline or incapable of knowing their proper place in the U.S. body politic. In short, white violence is an aberration, but violence is intrinsic to the African American, a supposition that is rationalized in a cruel circular (il)logic as located in the body’s very blackness.

OITNB is particularly suited to an examination of the workings of intersectionality; the discursive framing of black and brown bodies as inherently out of control and violent (O’Sullivan); and the figuration of racial identity as a U.S. reformulation of traditional tribalism (a reformulation that both shows persistently transgress). OITNB and Sense8 are important cultural texts, especially since the 2016 elections and recent events, and especially given the global entertainment hegemony of the company that funds, produces, and streams these two shows.4 Both shows are important cultural texts also because they quickly garnered devoted fans as well as attracted favorable media reviews and, in the case of OITNB, scholarship. Moreover, both shows exhibit groundbreaking originality in terms of premise, scripting, and casting. Most important, they not only critique and deconstruct the ideology and apparatus of white supremacist heteronormativity they evince a radical rethinking of human-being, of the maturation of the individual-as-part-of-the-collective, and of the collective itself. This rethinking aims to undo the essentialist binary paradigm that structures prevailing identity constructs of race and gender.

Methodology and Collective Individuation

The argument of this chapter grew from several considerations: (1) a concern with the ways that otherwise incisive criticisms of racism and a racialist worldview in television studies fail to move beyond the dominant essentialist and binary concept of racial and gender identity. Most critiques of OITNB published in academic journals so far fall into this category (Caputi). This consideration is based on Paul Gilroy’s trenchant argument “against race.” Gilroy writes,

It is impossible to deny that we are living through a profound transformation in the way the idea of “race” is understood and acted upon. Underlying it there is another possibly deeper, problem that arises from the changing mechanisms that govern how racial differences are seen, how they appear to us and prompt specific identities.… the creative acts involved in destroying raciology and transcending “race” are more than warranted by the goal of authentic democracy.… The first task is to suggest that the demise of “race” is not something to be feared. (11–12)

(2) The limitations of prevailing social science–based, empiricist methodology to measure the impact of televisual texts on the formation of race-d and gender-ed subjectivities; (3) the limitations of reading or interpreting televisual texts solely as if they are literature; (4) the emerging algorithmic calculus used by media giants such as Netflix, which upends current scholarship relying on tools that track viewership numbers and demography5; and (5) similar to item 2 in this list, viewership numbers and demographic data that cannot adequately explain the dynamic, fluid, unpredictable, and sometimes self-conflicting nature of subject formation, including the all-important impact of other cultural texts, discourses and interactions, the role of cognitive development, and the functions of memory and affect.

The goal of this chapter is not to diminish the invaluable antiracism work that has been accomplished in media studies; instead, I explore the capability of some of the ideas of Gilles Deleuze, Gilbert Simondon, and Rosi Braidotti to radically undo the binary paradigm structuring identity categories. Their ideas can open up a new vector of social science–based, cultural studies–centered analysis of the fictive media landscape. To Braidotti, “new figurations” or “alternative representations and social locations” are needed “for the kind of hybrid mix [in Sense8, for example] we are in the process of becoming” (2).

To be clear, OITNB and Sense8 do not instantiate a postracial United States; instead aspects of scripting—in terms of plotting and choice of narrators—reveal a possible pathway beyond the prevailing essentialist racial paradigm. Both shows contain a radically alternative configuration of the individual as a process of becoming, not in the sense of becoming someone, that is, of achieving a somehow intuited or socially normative end point using innate essences—colloquially, who I really am or who I am meant to be. David Scott’s monograph discusses Simondon’s framing of the problem thus, “The ontological and epistemological privilege … granted to the individual by psychology, sociology, and other philosophical theories presumes a uniting of a metaphysic of substance with an underlying hylemorphism.6.… [but the problem is one of begging the question] the principle of individuation is made anterior to the process of individuation itself, thereby promoting the constituted and given individual as the only starting point” (31). Scott notes that, in contrast to a substantialist or hylemorphic schema of individuation, Simondon’s conceptualization of living individuation consists of successive and simultaneous acts of social and psychological reformation … “ever partial, incomplete.… The living being is itself partially its own principle of individuation” (33). Furthermore, and this idea is crucial in Simondon’s thought, “a living being exists as only always a becoming between individuation, not as a becoming after individuation” (37); a living being is “at once the individuating system and its partial result” (33). “System” does not denote a preestablished roadmap or routinized procedure, nor does it presuppose a transcendental, preexisting essence. Rather, “system” is derived from the living being existing as “only always a becoming between” phases of transformation that do not seek to rise to meet ideal, external forms or matter or to materialize from an internal essence, if indeed essence exists. Muriel Combes’s metaphor of a rhizome may be useful, “like a crystal that from a very small seed grows in all directions within its aqueous solution wherein each molecular layer already constituted serves as a structuring base for the layer in the process of forming. Transduction expresses the processual sense of individuation” (6–7).7 The ways in which the characters in OITNB and Sense8 proliferate, to connect or merge or intertwine, unpredictably, in response to unanticipated occurrences is a figuration of a rhizomic becoming.

To critique and to criticize OITNB and Sense8 in terms of racist and gender stereotypes is useful as a response to persistent racist tropes in the overall cultural cartography (Enck and Morrissey). However, this criticism does not remove the mechanics or the generative ground enabling the circulation and re-formations of racist and sexist discourse; to a disturbing degree, this type of criticism requires the existence of the offense, too often serves to harden the offensive trope in the collective imagination, and presupposes the existence of the ideal, the true, and an authentic essence of identity. In other words, this kind of anti-stereotype criticism, though still important to undertake, often derives from and reaffirms the prevailing paradigm. I shall discuss in more detail the issue of stereotypes and OITNB later in this chapter.

OITNB and Sense8 transgress the predominant, conventional narrative plot and protagonist–antagonist structure of televisual texts to a degree that enables viewers to envision in these series radically different worldviews, whatever the intentions of their creators, respectively, Jeni Kohan and Lana and Lilly Wachowski and J. Michael Straczynski (Sense8, season 2 in its entirety was released in May 2017. Netflix has since canceled the series, citing the cost of supposedly $8 million per episode). First, writers have decentered the idea of a single protagonist, the essential character to whom viewers are sutured, are led to identify with, are induced to see themselves in, to compare themselves, or to pattern themselves after. The significance here can be grasped if we contextualize the conventional, single protagonist within a long, patriarchal and masculinist tradition dating back to Aristotle. That figuration of the male hero is typically dominating, aggressive, and frequently violent. Over the many centuries of the development of storytelling, the heroic, aristocratic, divine, or superhuman qualities of male protagonists have...