![]()

CHAPTER 1

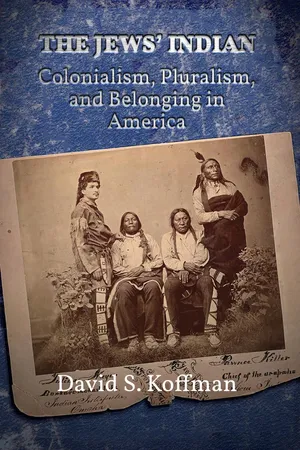

INVENTING PIONEER JEWS IN THE NEW NATION’S NEW WEST

In the summer of 1877, at age eleven, Sam Aaron joined a six-horse stage en route from Cheyenne, Wyoming, to Butte, Montana. He considered himself an intrepid traveler and a rugged, Indian-taming frontiersman despite his prepubescence. “I absolutely knew no fear; nothing was too hard or too dangerous to undertake,” he later wrote in his 1913 reminiscences. “I’d go into the wilds and ride for days without seeing a human being. The Apaches were on the warpath, killing and stealing.”1 However antagonistic Aaron perceived white-Apache relations to be, and however boldly he presented himself a hero, he nevertheless gave some thought to the conditions that led to settler-Indian tensions. “In those days,” he reflected, “all reservations were controlled by the Indian agencies in Washington, DC. Those agencies caused the restlessness of the Indians. Instead of giving them the allotment, they would hold back some of it and the Indian was always in need and therefore, committed crimes. He felt he was being cheated of what was due to him.”2 But the sympathy and moral favor Aaron found in “the Indian, [who] had a good many principles,” had its limits. Remembering one occasion, years later, after five workmen had been killed in a charcoal camp near Fort Haucha, Arizona, Aaron described how two white camp workers “killed one of the redskins, cut his head off and brought it into Charleston [Arizona]. I took the Indian skull, burned off the flesh and hair, sand papered it and made a beautiful skull. I said, ‘Jim, I have something I want you to do. Climb that pole and put the Indian skull on it instead [of the flag].’”3 In “beautifying” a murdered Indian’s skull, Aaron suggested that it replace the American flag atop a flagpole, symbolically marking the frontier West as land won by the grit and independence of stateless men.

When Aaron, “a Main street clothing merchant, but a former pioneer of the frontier,” reminisced about his life in Arizona, Utah, Montana, Wyoming, and California, he told the tale of his transformation from a frontiersman preoccupied with outlaws, shootouts, drinking, gambling, “wild Indians,” and the general mystique of the Wild West to an upstanding citizen-businessman at the center of a western boomtown. Tales like his, he boasted, “keep alive the memories of the early history of the frontier,” a history, he fretted, that might be lost. Conjoining adventure, mobility, and opportunity, Aaron cast his family history as one in which his forefathers, stripped of their Jewish pasts and rinsed of whatever linguistic, culinary, cultural, and aesthetic particularities marked them as new immigrants, followed the arc of the mythic settler West, beginning out of nowhere with the call of the wild and ending with the rugged frontiersman transformed into an upstanding main-street merchant. He did not, notably, tell the family story as one in which immigrant outsiders became part of the social fabric of new settlements on those lands America’s imperial expansion enterprise captured. Aaron’s elision of an immigration narrative altogether, his naturalizing of his family story, evinced a transformation already completed. But Jews had to become pioneers. They had to come to see themselves as embodiments of frontier settler identities and shed ideas of themselves as old-world newcomers.4

Like so many other Jewish memoirists from the late nineteenth-century West, Aaron glorified frontier life and the victorious outcomes of violent clashes with Native peoples, seeing his role in bringing commerce as paramount in the making of early settlement. Though he and his fellow settlers became domesticated, he conveyed the violence they perpetrated against Natives without discomfort. In telling his story, he helped create the image, the mythology, of the “earliest days” of Jews in frontier life. He wrote himself into this mythology, and he, along with dozens of western Jewish memoirists, newspaper journalists, family, and local history writers who are the subject of this chapter, turned this mythology into history, a celebratory story in which Jewish immigrants became pioneer Americans.

This process transpired in historical context. The mass movement of migrants to the United States from the 1820s to the 1920s impacted everyone and everything in its wake, including both the Jewish immigrants and the Native peoples they encountered. For millions of European immigrants, Jews among them, migration to the American West meant social mobility, relative economic security, and the creation of dozens of new communities with new textures and new timbres. For America’s Native populations, most of whom had been removed to ever-shrinking parcels of land in western landscapes that became sites of intense development during those same years, the migration of settlers meant displacement and dislocation, economic turmoil, political bedlam, and radical cultural transformation. Sam Aaron’s celebration of the “winning” of the frontier reveals how Jews saw their becoming settled and the role that Indians had in this process.5

Jewish men from Alsace, Bavaria, Posen, Prussia, and other German territories began migrating to the American West starting in the 1820s, with Jews migrating from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, Lithuania, Poland, other parts of eastern Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and elsewhere from the 1850s onward through the first decades of the twentieth century. They joined many already landed first-, second-, and even third-generation American Jews migrating west concurrently and thereafter. They left a Europe in which state powers generally prohibited Jews from owning land. Many Jewish emigrants lacked robust diets and faced potentially lethal conscription and unpredictable violent persecution. Many struggled to gain or maintain citizenship rights in their counties of origin. In 1880, some 80 percent of Jewish men and women living in western American towns had been born outside the United States.6 They had been pushed by limited employment options and pulled by the promises of social mobility, civic inclusion, and religious freedom. The West’s bounty—particularly gold, silver, and fur—and the small-scale commercial opportunities generated by those looking to exploit it drew them in chain migrations through family and social contacts.7 Between the 1840s and the 1880s, the Jewish population in America rose from 15,000 to 250,000, with new immigrants generally settling in cities—first in New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, Baltimore, and New Orleans, then in fast-growing cities like Cincinnati, St. Louis, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, Sioux City, Omaha, Milwaukee, Santa Fe, and Kansas City—and in dozens of smaller towns spread in between. In the West, the Jewish population grew to an estimated 300,000 by 1920.8 Between 1881 and 1924, some 2.5 million Jews immigrated to America, a ten-fold increase from the six decades prior.

Once in the West, Jewish men occupied a range of vocations, including wagon drivers, freight haulers, salon keepers, lawyers, journalists, physicians, clergymen, railroad and irrigation workers, and soldiers. But the vast majority of them began their careers as peddlers and merchants. From this occupational profile, they built the institutions of Jewish social and communal life as the contested and unripe frontier zones transformed into established and settled towns and communities.9 Immigrant newcomers headed to the margins to find and open new markets. Jewish businessmen supplied merchandise, packs, and maps to Jewish peddlers and traders who traversed underdeveloped territories. Popular historians of Jewish America Kenneth Libo and Irving Howe described these petty merchants as the “economic spearheads pointing toward a rapidly expanding frontier.”10 They traversed geographic zones with little settlement where they supplied mining camps, army forts, farms, boomtowns, and trade routes with dry goods. The pattern persisted fairly consistently in the states west of the Mississippi River. First came unmarried men who worked itinerantly for a period of time before forming basic Jewish communal institutions like burial societies and prayer quorums. Many men brought brides and wives from their hometowns in Europe or from larger cities in the American east. Once they arrived, Jewish women tended to stabilize the places where Jewish men had settled, helping build Jewish communal structures and organizations and networking dispersed homes into communities.11 The West offered ample opportunity for speedy social mobility in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, more so than elsewhere in the United States.12

While Jews brought with them versions of their material, religious, and intellectual cultures, few brought great attachments to the European states in which they previously lived. They formed new and often intense commitments and ideological bonds, however, to the new republic and to the white citizenry that produced and embodied its values. Among whites, frontier society offered a pragmatic class structure into which Jews fit generously, although not without tensions.13 While historians contest the rhetoric of ethnic and class openness of the West in general, relative to their experience elsewhere, particularly in their lands of origins, Jews experienced weak anti-Semitism.14 Perceptions of Jews’ biological, religious, or even moral differences operated in the West, as they did in the South and East, but Jews suffered relatively minimal victimization there. The very diversity of the West placed Jews in an advantageous position. Whites, Jews included, had others to marginalize and, at times, exploit and persecute—particularly Asians, Blacks, Mexicans, and Indians. Both immigrant and American-born Jews, in other words, enjoyed the privileges of whiteness from their immediate arrival in the American West.15

For Native Americans, the last two-thirds of the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth proved radically disruptive as a direct result of European and American migration, or conquest. In 1820, nearly every Native tribe west of the Mississippi lived on its ancestral lands, although the government had been engaged in systematic efforts to acquire land legally, semilegally, or illegally from Native Americans through treaty signings. Native American land loss was also wrought by settlers’ often violent squatting or cozening, later defended by legislation, the courts, sheriffs’ offices, and the military.16 The federal government’s adoption of removal policies, beginning in the 1810s and nationally sanctioned by President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act in 1830, forced thousands of Native Americans from their lands in Arkansas, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, and Nebraska and produced a ripple effect of land relocations. These relocations disrupted subsistence patterns as well as cultural traditions and produced shifts in language patterns that adversely affected Native communities.17 Even before the introduction of the Dawes General Allotment Act in 1887, the federal government implemented policies aimed at assimilating Indians to white ways, separating children from parents and sending them to state-run residential schools, banning a number of religious traditions, and attempting to force certain tribes to subsist through farming.18 Between 1871 and 1934, either the American government or white settlers enabled by government policing took possession of more than two-thirds of tribally entrusted lands, some ninety million acres.

In memoirs like Sam Aaron’s, Indians served as foils for both Jewish and American identity formation. Indians lay at the heart of a key slippage between immigrant and pioneer in many nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American western Jewish memoirs, and indeed, Indians served key rhetorical functions in much of western American Jewish writing in general.19 Using Indians this way was but one use among many that American Jews put to the “Indians” of their writing (memoirs, history, news stories, cultural products, etc.). Immigrant Jews, like other whites in the emerging American West from the last quarter of the nineteenth century to the first quarter of the twentieth, fashioned themselves as “pioneer Americans” through their interactions with Native Americans, both imagined and real. As this chapter will show, American western Jews used both techniques of opposition (showing themselves to be different from, and even opposed to, Indians) and techniques of relation (showing themselves to be essentially or largely the same as Indians). Jewish men cast themselves in the role of frontiersmen, fitting themselves into the well-worn narrative form of American frontier culture when they wrote letters, diaries, and newspaper articles contemporaneously to their settlement and, retrospectively, when they wrote memoirs, family histories, and local histories. Both concurrently and retroactively, Jews mobilized frontier mythology as they envisioned themselves and their roles in the West. The uses to which Jews put Indians continued consistently over time as Jews became settled and Native Americans “pacified.” Jews wrote themselves into western narratives and employed the same rhetorical techniques to affect their belonging whether they arrived in the West in the 1850s and remembered it retrospectively in the 1890s or they arrived in the 1880s and remembered it retrospectively in the 1920s. Remarkably little changed in the making of pioneer Jews over three-quarters of a century.

Jewish memoirists, letter writers, family storytellers, journalists, local history writers, and professional history writers of Jewish life in the West played with the tropes and conventions of the popular West. They aimed to craft accurate and evocative narratives of their western experience; they reproduced, perhaps less than fully consciously, the tropes, stereotypes, and conventions of settler heroes, frontier lore, and “othered” Indians on which they were fed. Several features comprised the frontier archetype into which Jewish men molded themselves as they migrated and wrote of their family’s and community’s “early pioneer days”: rugged individualism, brawny masculinity, intimacy with the natural landscape, rigorous physical workmanship, and encounters with Indians. Archetypal American frontiersmen understood the great distance between themselves and the “wildness” that the Indian other supposedly embodied. In the American cultural imaginary, the frontiersman could be expected to tame, pacify, civilize, remove, or kill Indians to prevent their disruption of settlement’s way. The frontier white could also be expected to affect Indians’ assimilation into civilization by means of conversion to Christianity or through transforming the Indian from a sustenance-oriented primitive to a productive member of capitalist society, be it commercial or agricultural.

While certain aspects of this persona required a dominating and distancing stance toward the Native other, being a true frontiersman also, paradoxically, required a degree of closeness and identification across perceived differences. The frontiersman knew something of Native Americans’ ways, seemed comfortable among Native people, and had learned the ways of tribal life and language. He might even be accepted as an “honorary Indian,” having lived among tribes for stretches of time and later reemerged into white civilization wiser, more in sync with the earth, with the soil of America itself, and with improved spirituality. The identifying impulse and the distancing impulse formed flip sides of the same coin, one that used Indians as a foil for the achievement of American national identity. As an ideology that also served to help expand America’s territory and economy, this discourse both abetted and obscured the subjugation and displacement of Native Americans.20

Jewish immigrants had internalized Frederick Jackson Turner’s influential idea of the frontier as a zone ...