![]()

1

The Performance of Memory

Miriam Katin’s We Are on Our Own, a Child Survivor’s (Auto)Biographical Memoir

A thick and densely populated silence.

—David Grossman, “Confronting the Beast”

There is no easy story in legacy. What is remembered and what is forgotten?

—Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance

So, where does a story begin?

—Miriam Katin, Letting It Go

Miriam Katin’s graphic memoir We Are on Our Own (2006), the story of her experience as a child in Hungary during the Nazi invasion, is told from two competing and often conflicting perspectives: the limited vantage point of a young child survivor—Katin is two years old at the time of the German invasion of Budapest—and that of her mother, whose memories of their experience in hiding are mediated through her daughter’s illustrated articulation of them. We Are on Our Own, through the dialogic interplay of text and image, mediates these differing perspectives. It is only through the hindsight born of age and experience that Katin, as an adult with a child of her own, can belatedly recover and attempt to articulate the events she was subjected to as a child as well as the approximate emotions and sensations of an experience that she only now obliquely—guided by her mother’s stories—“remembers.” Katin, animator and graphic artist, came to this project late in life, drawing her first memoir when she was in her sixties. Commenting on the belated origins of her attempts to draw the narrative of the past, Katin explains, “The stories my mother told me about our life and survival during WW2 and the fate of our family . . . were always with me. A daily uninvited and unwanted presence. They begged to be told. But . . . I thought who needs another Holocaust book anyway. However, when I discovered for myself the world of comics, I realized that I can draw these stories.”1 We Are on Our Own is Katin’s attempt to perform the memory of her childhood encounter with the Nazi assault on Hungary’s Jews, with the aggressive incursion of the Russian troops, and with her and her mother’s perilous and uncertain escape. In doing so, Katin draws herself into the trauma of her past, creating an aesthetic of affect, the textures and collisions of memory. Drawing largely upon expressionistic and impressionistic images of affect,2 Katin is able to “visualize . . . to herself”3 that which she can only “remember” through her mother’s fragmented stories as well as those artifacts of the past, those personal letters and postcards her mother had written to her father and the more impersonal, public accounts and documents of the period. Katin is thus both the subject and object of her memoir. In drawing herself as a child pursued by forces over which she had no control, she creates the conditions in which she both appraises and observes as other and at the same time is a spectator of the outside world from inside the position of her younger, imagined incarnation.4 Subject and object, observer and observed are conflated in her attempts to reenact the complexity of the experience and the articulation of memory.

Beginning in Budapest in 1944, “a city of lights, culture, and elegance,”5 her story narrates a life ruptured and inverted, the very precepts and patterns of belief and the shape of the world she and her parents inhabited eroded by the Nazi occupation of Hungary. In graphic form, Katin draws the abrupt and devastating reversal of her family’s condition: the Nazi onslaught, the legislated rise of overt antisemitism, her father’s enlistment in the Hungarian army, and their displacement from home and community. Disguised as Hungarian peasants—“a village girl with an illegitimate child”—mother and daughter alone will navigate on foot through the Hungarian countryside, taking precarious and itinerant refuge where they can.6 Moving from one temporary shelter to another, motivated by the predatory pursuit of those who hunt them down, theirs becomes a life circumscribed by flight, by disguise and concealment, and by the imminent danger of exposure. Katin charts the condensed experience of their lives together in hiding from 1944 to 1945 as they navigate the tentative generosity of strangers, the constant fear of discovery, the passage through unknown and hostile terrain, and the confusions of an uncertain future. In doing so, Katin disrupts the temporal, spatial, and narrative linearity in her graphic manipulation of panels and page layouts in an attempt to materialize the visualization of trauma in order to evoke both the complexity of the extended moment and the complexity of giving voice to the memory of the experience.

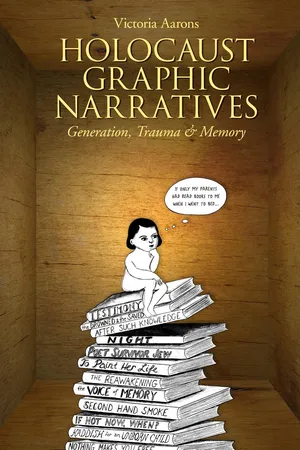

The title of Katin’s memoir suggests the lesson learned well by the child who survived only because of the fortunes of circumstance and her mother’s ingenuity and fortitude. One thing is very clear: as the narrator’s father, reunited with his family at the end of the war, unequivocally pronounces, “We are on our own. . . . That’s all there is.”7 Theirs is a condition without intercession or arbitration, as even the young child perceives, “Not anybody at all.”8 Indeed, throughout most of the narrative, mother and daughter together are “on their own,” cast precariously about, abandoned by the civilizing interventions of human decency and restraint but also by exhausted notions of god. The first page of the graphic memoir consists of a large, slightly off-centered square darkened by scribbled black lines and swirls that extend haphazardly beyond the borders of the panel. Inside the large black block is a smaller square, left uncolored save for the inside edges marred by the uncontrolled scribbles of lines. The opening image thus evokes a child’s attempts to draw the square within the square, a child’s drawing that is, as yet, unformed—lines that cannot be contained within the experience of the frame within the frame. Right from the start, then, Katin emphasizes that the story we are about to be told is from a child’s perspective. In fact, the construction of the book itself reminds us of a young child’s illustrated book, its cover made of hard cardboard, its small, square size designed for small hands, the pages a thicker, more resistant weight, the images on the cover as well as the internal pages, as Tal Bruttmann suggests, “drawn in the graphic style of a children’s book.”9 Yet the juxtaposition between form and content suggests a disturbing antithesis in which the appearance of the book and the subject matter of the drawings that proceed are at odds; right from the start, something is off. Such an ironic juxtaposition produces a jarring effect and establishes the uneasy anticipation that will be played out on the pages of the memoir.

Indeed, the background of the book’s cover is black, as is the large square that confronts us on the first page. The book thus promises to begin in a state of chaos as is made emphatic in the writing within the white square in the small center of the large black square askew on the first page: “In the beginning darkness was upon the face of the deep.”10 The “face” of the black square consists of the diminishing light that takes us back to a mythic time before the formation of life itself, an appropriate beginning that anticipates the formation of a coherent universe out of the chaos of the deep dark. The opening page is followed by a close-up of a black splash that, in the next two panels that zoom out, is shown to be a Hebrew letter that begins the text of the making of the world in Genesis, God’s creation of the light that is only the beginning of the covenantal promise of a future. Yet as the young Katin’s mother explains to her daughter in the following panel, “God divided the light from the darkness,” only on the following page to take back that first act of creation, the dark rapidly eclipsing the light.11 In many ways, Katin’s memoir is a meditation on the death of god, or the death of an idea, a civilizing structure, and an ethical frame for living among others. God as the architect, evaluator, and judge of all things and created, in the young child’s hierarchical order of importance, “the dark, then the light, then mother and me and then the others” and pronounced the light “good,” only to abandon—arbitrarily and in something of an afterthought—the covenant.12

Here not only is the credibility of a benevolent, meaningfully designed universe forsaken, but such a framework for belief is irreversibly capsized: the opening pages of the narrative show the Hebrew words of Genesis eclipsed by the regressive impulses of malevolence, the Hebraic letters replaced by the symbol of the swastika and captioned with the unnerving liturgical cadence of the line “God replaced the light with the darkness.”13 We view this rapid exchange on a two-page spread; thus we are asked to see this abrupt reversal as one—that is, as a reimagining of beginnings, of the origin story. Such a re-envisioning of the point of departure disturbingly recalls Melvin Jules Bukiet’s received knowledge that, for the children of survivors, “in the beginning was Auschwitz.”14 Indeed, Katin opens her memoir with varying temporalities, geographies, and narratives in what would seem to suggest her attempts to locate an introductory framing, organizing principle for the narrative: in rapid succession, the opening pages shift from the child and mother in seeming ease poring over the scriptural text of the Hebrew Bible, only to shift in the next page to the Nazi flag overtaking the view from what we imagine to be their window, to shift again as we turn the page to the year 1968, to an adult Katin with her new child, surrounded by family and warmth, only to transfer again on the facing page to 1944 and Budapest before the Nazi occupation, followed once again by the threat of impending disaster. Such jarring, erratic, juxtaposed movement from scene to scene, from one time to another reflects the instability of memory and also traumatic recall. Thus Katin conflates in these opening pages time and comportment, inviting the reader to see the predicament of individual lives within the sweep and arc of the wider historical moment and its aftermath for the author and her mother.

Katin’s narrative perspective is complicated by her age at the time of the events she relates, events that she can only now, with the guide of maturity and experience as an adult with a child of her own, begin to understand. Thus Katin writes from a dual perspective: she is both a survivor, a witness to events she experienced directly yet whose implications she did not at the time appreciate, and a second-generation chronicler of events filtered through her mother’s memory and her own imaginative, projected reinvention of both the events and their meaning at the time of their occurrence. Complicating further this mix of perspectives and an amalgam of all these is her perspective as an authorial presence in writing the memoir. Putting herself in her mother’s place, Katin displaces her deferred anxiety onto her mother, but she also displaces her mother’s past terror and dread onto her own more proximate and residual fears and her belated awareness of the danger she was in. Thus the remnants of memory as they exist on the periphery of her consciousness as well as the unconscious return of past trauma control the unfolding of the narrative.

Katin is part of what Susan Suleiman refers to as the “1.5 generation”: “child survivors of the Holocaust, too young to have had an adult understanding of what was happening to them, but old enough to have been there during the Nazi persecution of Jews.”15 As Suleiman suggests, these were survivors for whom “the trauma occurred . . . before the formation of stable identity . . . and in some cases before any conscious sense of self.”16 As a very young child at the time of her ordeal, Katin does not have distinct memories of the events that her mother has related to her, and thus she must reach into her mother’s memory of the past in an act of imaginative creation. Her position is characteristic of other young children for whom the memory of their displacement and imminent peril exists only on the periphery of their consciousness. As such, the child’s limited consciousness of events and surroundings complicates the process and articulation of memory. As Katin said in an interview with Samantha Baskind, “As I was very young, my real memories of that year are very scant. I am grateful for that. What I most remember is connected to food and the lack thereof; the little dog that I befriended and then had to leave behind when my mother and I were on the run, which I describe over the course of several pages, culminating in the dog being killed and my mother and I later finding him bloody in the snow; and the bombing that I witnessed.”17 Such limitations and “flawed,” imperfect memories, however, do not detract from the literary expression and production of repressed memories, according to Suleiman, “powerful accounts of what it felt like to be a child . . . during the Holocaust, encountering loss, terror, chaos [in which] we see both the child’s helplessness and the adult’s attempt to render that helplessness, retrospectively, in language.”18 Similarly, child survivor Irena Klepfisz, whose wartime experiences in hiding in the Polish countryside were not unlike Katin’s, describes in the prose poem “Bashert” her lack of awareness during the time in which she and her mother—both terribly alone, ill, and desperate—were imperiled and in disguise: “I am over three years old. I have no consciousness of our danger, our separateness from the others. I have no awareness that we are playing a part.”19 While child survivors who were too young to remember the events or even to have perceived their peril at the time in which the events were taking place look back into an empty space where memory conditionally might have been, such vacuity is in part compensated for through a creative reenactment of their experiences.

It is thus through the narrated repetition of events that the child survivor is able to wrest some control over the uncontrollable past and perhaps conquer the belated fear of what might have happened. Cathy Caruth, in Literature in the Ashes of History, a very interesting study of psychoanalysis and the disappearance of history, argues that the failure of memory symptomatically results in repetitive return narratives, “a return to the site of catastrophe to grasp an origin that marks the beginnings of [the] urgent desire to remember.”20 Such a “return” might be figured in an actual return to the physical site of the catastrophe or an imaginative return through, as Caruth suggests, “the creative act of language.”21 Caruth’s discussion of Freud’s example of the child who engages in the repetitive game of departure and return, of “fort” and “da,” “gone” and “here,” as a means of negotiating the fear of the loss of the mother is pertinent to our discussion of child-survivor return narratives. The graphic reconstruction of the catastrophic time before memory might be likened to the repetitive game played as a means of gaining control of one’s unconscious impulses and fears. The “repetitive game,” then, played out indirectly by way of the narrative, constitutes a return to, or repetition of, the “lost” experience, the origin of the anxiety not only about absent memory but also about the contingency of a life that might have been lost. The “return of the traumatic experience,” as Caruth suggests, “is not the direct witness of a threat to life but rather the attempt to overcome the fact that it was not direct, to master what was never fully grasped in the first place. . . . The life of the survivor becomes the repetition of the reality that consciousness cannot grasp.”22 Thus returning to the traumatic moments or occasion of the past, in the instance of Katin’s child-survivor narrative, might be thought of as a way of performing or reenacting the trauma in order to control it.

Thus Katin’s mother’s stories evoke in her a kind of imaginative recall, a symptomatic response to experiences that she absorbed unconsciously as she witnessed and felt her mother’s fear in the way that children are deeply in some primal way attuned to changes in their mothers’ affect. After all, the extent to which Katin’s young life was so dramatically ruptured and reconfigured cannot be overestimated: a once present but suddenly absent parent, the result of her father’s conscription in the Hungaria...