![]()

1

Economy and Security

1. Cold War Two

The times are peaceful and yet wars are on. We are beset by a number of regional conflicts and local clashes, but they represent a lesser evil than a great global explosion. Luckily, disputes between the titans of the world have been bloodless to date. There are no saints here when it comes to intentions and acts as none of the three most powerful contemporary actors on the political and military scene – the United States, China and Russia – is free from guilt. All three are flexing their muscles, which damages international relations and reeks of a new cold war, while doing harm to economic cooperation and to efforts to create a more inclusive version of globalization.

Unfortunately, we can already speak of Cold War Two. That’s how I referred to the present state of affairs several years ago, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War. Back then I wrote:

One hundred years ago a war was unleashed. It lasted for almost four and a half years, millions of people were killed. In the beginning nobody realized it would be a world war, but it quickly turned this way. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was referred to as the Great War. It took another war, breaking out 25 years later, to get the previous one, that of 1914–1918, the name of the First World War. Soon after the Second World War, that of 1939–1945, was over, the Cold War was unleashed. This was done by the West in confrontation with the East, which was defeated decades later. It even so happened that after 1989 the ‘end of history’ was announced on that occasion. How prematurely …

After only generation of more or less peaceful times, Cold War Two was started. Indeed, the one of 1946–1989 will be referred to by historians as Cold War One. It was won by those who started it: the West. Now the West, too, is getting Cold War Two started. But it won’t win this one. Neither will the East win it. It will be won by China, which is doing its own thing, most of all consistently reforming and developing the economy, whose international position is strengthening with every year that passes. A few years, or over a decade from now, when both US hawks with their allies, and those from Russia, get weary of their cold war imprudence, China will be a yet greater superpower; both in absolute terms and relatively, compared to the USA, European Union, Russia … Also the position of other countries, including the emancipating economies refusing to be dragged into another cold war turmoil, will be relatively better. (Kolodko 2014d)

Well, that is exactly the goal: not to get dragged into it.

The richest country in the world, the United States, instead of increasing its aid expenditure, mindful of co-creating economic foundations for peaceful development, cuts it to free up more funds for armament. Even though the level of the latter is already very high, the US Senate is pushing for a further increase of 80 billion dollars in 2019 and 85 billion in 2020 (BBC 2018b). As at 2018, the expenditure is set at 692.1 billion dollars, which represents an exponential 18.7 percent growth compared to the previous year. At the same time, Russia is reducing its military expenditure by 9.2 percent, cutting it to 2.77 trillion rubles (42.3 billion dollars) (Bershidsky 2017; Tian et al., 2017). This is surprisingly little compared to the United States, but relatively much more because while the United States earmarks ‘only’ 3.3 percent of its budget to defense spending, in Russia it’s around 5 percent. While the country’s president Vladimir Putin justifies the military spending cut with the need to increase expenditure on healthcare, education, science and culture (which should be applauded), his detractors are quick to point out that it’s only a short-term political marketing gimmick applied before the presidential election to be held in the spring of 2018 (which should be rebuked).

In China, the indicator describing the ratio of military spending to national income is nearly half that of the United States and stands at 1.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), but is growing quickly. In absolute amounts, Chinese military spending is merely a third of US expenditure, ca. 230 billion dollars a year, but let’s remember that there is also expenditure incurred which is in fact military, though it’s posted as purposes other than ‘defense’ – for example, some research and development spending that evidently serves the army is realized in the ‘science’ department. Let us add that this is not unique to the Chinese; others do the same.

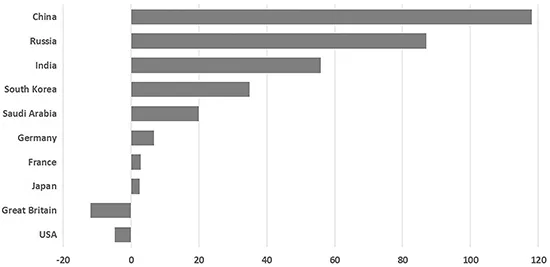

Hence, the Chinese military spending is still a small fraction of the US one, but it must be emphasized that while the United States, despite the recently greatly increasing outlays, is still spending less than ten years ago, China is spending nearly 120 percent more. It’s little consolation that others among the countries with the world’s largest military budgets have increased their spending to a much lesser degree.

Diagram 1 Changes in major military powers’ defense spending (percentage increase between 2007 and 2016)

Source: Own compilation based on data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Analysts in the field highlight the predominance of spending on defensive weapons and facilities in all of China’s defense expenditure. One of the major tasks in this area is to develop the sector manufacturing weapons that, in the event of a conflict, would push US military power back as far as possible from Chinese shores, preferably to the most remote Pacific areas. So, the point is to move the enemy army back rather than deploy one’s own forces closer to their shores. This strategy is known in the military jargon as anti-access/area denial (A2AD). This, by no means, prevents the development of various types of offensive weapons, including very sophisticated products such as drones, which China has started exporting on an increasing scale. While far behind the United States and Russia, as well as the UK and France in that respect, it is said that, with products having 75 percent capacity of the Western ones, China sells them at 50 percent of the Western price (Marcus 2018). To many buyers it’s a great deal, so, sadly, the arms race is again gaining impetus.

It is all the more worrying that the US president Donald Trump, rather than looking for conciliation and creating new channels for good international and global cooperation, a year after taking the world’s still most important office, announced that China and Russia are not so much the United States’ partners as rivals. It comes as little surprise, then, that even such an opinion-leading weekly as the Anglo-American The Economist cautions against the growing threat of an eruption of conflict between the superpowers. It was no coincidence that it did so in the issue published during the annual World Economic Forum in January 2018 to further raise the adrenaline level of politicians and business people, financiers and bankers, academics and media representatives meeting in Davos (Economist 2018a). So, do we have anything to fear? And if so, who and what is the threat?

In many parts of the world, there’s much scaremongering about China, its growing power supposedly threatening the peace of others. The country is feared not only by some from the same region, not only by the immediate neighbors such as Japan or South Korea, India or Pakistan, but also in more remote parts of the world, including the West, especially the United States and some European countries succumbing to Sinophobia. In others, on the contrary, China’s expansion inspires some hope for a more balanced world, a new global order where a counterbalance emerges to the dominance of the West, with its eyes fixed on its own interests only.

The anti-Chinese narrative is growing stronger, in particular, among the US establishment and some, notably conservative, media and parts of the social science community. Excessive irritability is certainly undesirable and harmful in the business sphere, though it can be justified in situations where capitalists and company executives get frustrated by their inability to keep up with foreign competition, which is often identified with China. It’s even worse if the ones losing their temper are politicians and lobbyists, as well as those linked to the media and the academic and research community.

What strikes me as something the world hasn’t seen for a long time, maybe since the last cold war, is the aggressive, more emotional than rational public attack (rather than cold matter-of-fact criticism) of The Economist weekly, which entitled its cover story ‘How the West Got China Wrong’. It argues that the West,

Bet that China would head towards democracy and the market economy. The gamble has failed. … China is not a market economy and, on its present course, never will be. Instead, it increasingly controls business as an arm of state power. It sees a vast range of industries as strategic. Its ‘Made in China 2025’ plan, for instance, sets out to use subsidies and protection to create world leaders in ten industries, including aviation, tech and energy, which together cover nearly 40 percent of its manufacturing. (Economist 2018d)

Well, it’s a fact that China, rather than adopting the path of Western-style deregulated market economy, follows that of active economic interference, by running a well-oriented industrial policy, which, mind you, many Western countries used to have in place, and some of them, for example South Korea, are still far from despising. If things were indeed as bad as persistently argued by those who are uncomfortable with the Chinese path because it makes life easier for the Chinese rather than for them, further considerations should be limited to searching for the answer to the question why this happened and what the implications are. However, the reality is far more complicated.

Of course, the criticism of China is by no means unwarranted as its economic policy and systemic solutions oriented to improving the internal situation can be costly for others, who, under the current circumstances, are unable to compete. Irrespective of the structural inability to equilibrate the US trade balance, which has been a major cause for anti-China resentments for some time now, there are also cases of China’s espionage activities in the United States and other Western countries, as well as various attempts to use soft measures to influence what goes on there. However, the Chinese could learn more about this from the Americans than vice versa.

The US trade deficit is, first and foremost, the result of the country’s weak and relatively uncompetitive export offering rather than unfair Chinese competition, as Donald Trump and other Sinophobes would have it. The time has come to understand that the fundamental cause of the uncompetitiveness of some US sectors is living beyond one’s means, which is manifested, among other things, by excessive wages, compensations and profits. In an extended cost/benefit analysis, wages emerge as the main factor determining costs, which ultimately turn out to be relatively too high on the liberalized world market. However, having recourse to protectionist practices will not be of much use in the long run, and a verbal attack on China will be of no use at all. It only ruins the atmosphere, which is already far from great.

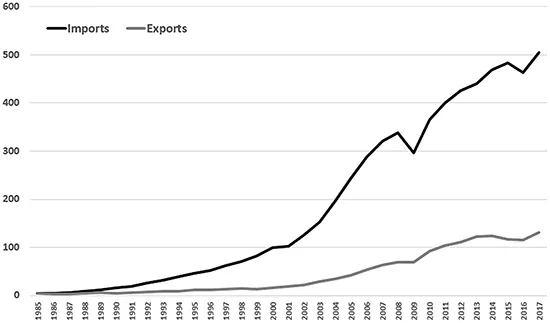

Diagram 2 US–China trade between 1985 and 2017 (in USD billions)

Source: Data from the International Monetary Fund.

When denouncing the truly immense surplus of Chinese exports to the United States over US ones to China, the countries’ bilateral relations are not given a comprehensive evaluation. Compared to its national income, for instance, Poland has a relatively much higher deficit in its trade with China but is able to balance this in total foreign trade, recording surpluses in other relations. Statistics tend to simplify the reality. It’s a fact that in bilateral trade relations there are twelve times fewer dollars paid to Poland by China for its direct exports going there than for imports from China. At the same time, cars, whose components are manufactured in Poland, are a substantial portion of German exports to China. Cars are the top-ranking item in the vast German exports, amounting to 1.4 trillion dollars, 6.4 percent of which go to China. Assuming that those German car exports contain, in terms of value, 10 percent of the Polish automotive industry’s products, the total amount is 30–35 billion zlotys (ca. 1.5 percent of GDP). Hence, if we conduct a comprehensive analysis, it turns out that the trade exchange with China creates a lot more jobs, income and budgetary revenues in Poland than it would seem on the surface of things.

The United States is unable to do that and constantly has a major trade deficit. In 2017, it amounted to 375 billion dollars in goods traded with China, with a total gap of 566 billion dollars. This fans the flames of rhetoric targeting China and some other countries, especially neighboring Mexico, but it’s still a far cry from the anti-Soviet aberration of the fevered McCarthy period of the 1950s. However, it’s a fact that in Washington DC scaremongering about China is rife. ‘Chinese efforts to exert covert influence over the West are as concerning as Russian subversion,’ says Mike Pompeo, then head of the US intelligence, CIA. ‘Think about the scale of the two economies … The Chinese have a much bigger footprint upon which to execute that mission than the Russians do’ (BBC 2018a). It has to make us wonder, if not worry, when this comes from one of Washington’s most influential politicians.

Quite contradictory pictures are being painted on the historic scale. In the first, imperialism – namely, the Western, capitalist variety – is supposed to be replaced with another, the Eastern and ‘communist’ version. Is this a real perspective or an ultimate irrationality (because neither is there communism in China, nor is the country striving to dominate the world)? In the second portrayal, China is presumed to save the world from the rampant economic and environmental dangers as it has the exceptional capacity for a long-term and comprehensive approach to problem-solving and is not selfishly focused on its interests only. The walls of our shared global house could be adorned with many more paintings that we could contemplate, as in a gallery of eclectic arts.

Contrasting values, conflicts of interest, ambiguous situations, unclear intentions cause the same facts to be interpreted quite differently. While not a word of criticism was breathed on the occasion of Angela Merkel being appointed chancellor of Germany for a fourth term in office, there was quite an uproar when the provision of the Chinese constitution limiting the presidency to two terms was scrapped. Passing over the fact that the key position in the Chinese political hierarchy is the chairperson of the ruling single party, with the president having actually little say, some are inclined to decide, for this reason alone, that from that moment on the current leader of China, Xi Jinping, becomes a lifelong dictator. Meanwhile, others emphasize that it’s the right move, which, in itself, does not determine who exactly will be wielding power, but, if necessary, enables continuity in the sphere of long-term development policy leadership. And that’s of crucial importance at a time when an increasing number of problems require a long-term approach.

While leaving the ‘dictator or strategist’ antinomy unresolved (and ignoring that, theoretically, one can be both), it’s worth emphasizing that sometimes the limit on terms in office of public officials, who are elected too often for too little time, is precisely what entails short-term thinking and actions, and the obvious negative consequences with respect to socio-economic development. This kind of short-termism, or shortened time horizon in which various alternative action scenarios are considered, surely is not characteristic of the Chinese policy; quite the opposite. Many a time this is what makes the Chinese way of steering the economy superior, because the negative impact of political cycles on the economy, so typical of Western liberal democracy, does not occur in China.

In this beautiful democratic world of ours, all kinds of referendums or elections keep taking place – in Greece or Italy, in the UK or in France, in Austria or the Netherlands, in Spain or Germany – whereas all is quiet in China … Somewhere in faraway Brazil, the president was impeached, somewhere closer, in South Korea, the president was also deposed, and in the South African Republic the president was forced to resign, whereas all is quiet in China … In North Africa and in the Middle East, the Arab Spring compromised itself, whereas all is quiet in China … Even in the supposedly institutionally mature and economically advanced European Union (EU), every now and then someone needs to be rebuked or removed from the position, whereas all is quiet in China … Well, at least relatively quiet.

China, with its specific economic and political system developed over the last seventy years, has become the focus of attention of many other catching-up countries. In a situation where classical development economics failed, and fail it did (Easterly 2002, 2006), to many an economist and politician – from Bangladesh to Senegal and Ecuador, from Asia to Africa and Latin America – the Chinese model that has proven itself in practice is worth an in-depth and critical observation, as well as creative adaptation and application back home. China is a unique state, which, in just two generations (from 1978, when the gradual market reforms started) is changing its status from that of a low income country (as per World Bank terminology) to a high income country, which level it is estimated to reach as early as 2024 (Hofman 2018).

When pointing to four fundamental differences between highly and poorly de...